Bone Cancer: What You Need to Know

An orthopedic oncologist explains the signs, symptoms, and treatments of bone cancer.

Primary bone cancer is a cancer that originates in the bone when cells grow out of control. Also known as sarcoma, it is a rare form of the disease, accounting for less than 1% of all cancers, according to the American Cancer Society. (Sarcomas are different than the cancer from tumors in other parts of the body that metastasize and spread to the bones.) In 2020, there were about 60,676 people living with bone and joint cancer in the United States.

“We have different types of cells that make up our bones. Primary bone cancer starts when these cells begin to grow out of control,” says Dr. Wakenda K. Tyler, chief of orthopedic oncology at NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving Medical Center.

Dr. Tyler spoke more with Health Matters about bone cancer, including the different types, the symptoms, and treatments.

Dr. Wakenda K. Tyler

How does bone cancer start?

Bone cancer can begin in one of two ways. The more common kind of bone cancer is from cancer that begins somewhere else in the body and spreads to the bone. In those cases, the cancer cells will look like the ones from the organ the cancer spread from. This tends to occur with advanced-stage breast, prostate, and lung cancer.

The less common bone cancer is primary bone cancer, which originates in the bone.

What cells do we have in our bones and how do they become cancerous?

Our bones contain osteoblast and osteoclast cells. Osteoblast cells form bone, and osteoclasts eat old bone to essentially remodel the bone. We also have other cells, such as lipoblasts that come from fat, and cartilage cells that act like shock absorbers to protect our joints and bones.

All these cells come from mesenchymal stem cells, which are cells that help make and repair skeletal tissues, like cartilage, bone, and fat, in the bone marrow. Bone marrow, at the center of our bones, contains blood vessels.

When someone develops cancer in the bone, one of these cells — and oftentimes we think it is the mesenchymal stem cells — suddenly grows out of control, causing chaos. This chaos eventually becomes cancer, which is capable of invading and leaving the bone, entering other parts of the body nearby.

What are some different types of primary bone cancers?

There are three main types of primary bone cancer:

- Osteosarcoma

Osteosarcoma is the most common primary bone cancer and most often occurs in people ages of 10 and 30. It arises from the osteo cells, the cells that produce osteoblast, with tumors developing often in the arms, legs, or pelvis. - Chondrosarcoma

The second most common type is chondrosarcoma, which begins in the cells that produce cartilage. It most commonly develops as people get older and in the pelvic bones, legs, or arms, as well as other parts of the body, such as shoulder blades or ribs. - Ewing sarcoma

With Ewing sarcoma, we do not fully understand what the originating cells are, but they form this small, round blue cell cancer in the bone. The cancer can also develop in tissues and organs in the body. Ewing sarcoma is most common in children, adolescents, and young adults.

What are the symptoms of bone cancer? What does bone cancer feel like?

The major bone cancer symptom to look out for is bone pain, which is not like other types of functional pain, such as when you lift something and your muscles ache. Bone pain is a little more insidious, meaning that it can be subtle in nature and it feels like the pain is there even when you are not doing activities. Often people will experience this kind of bone pain while they are resting. At night, the pain will wake them from sleeping. It is a dull, aching, even throbbing, pain in the bone, like a toothache.

A symptom of a late finding of cancer in the bone is swelling, more stiffness, and loss of motion. This could be when the tumor starts to grow outside the bone.

Unfortunately, in certain areas of the body, you will not notice cancer growing because it is deep at first. You will not be able to physically see a swollen area.

Who is at risk for bone cancer?

There are rare genetic abnormalities, but I would say that 99% of patients that present with primary bone cancer have no genetic predisposition.

The genetic risk that we know about is a condition called Li-Fraumeni Syndrome, which people are born with. It is a mutation in the gene that puts you at risk for different kinds of cancer, including bone cancer, like osteosarcoma. Another is the retinoblastoma gene. Patients born with this gene usually know because they get retinoblastoma, which is a cancer of the eye, at an early age. And then they are at risk for developing osteosarcoma later in life.

How is it detected?

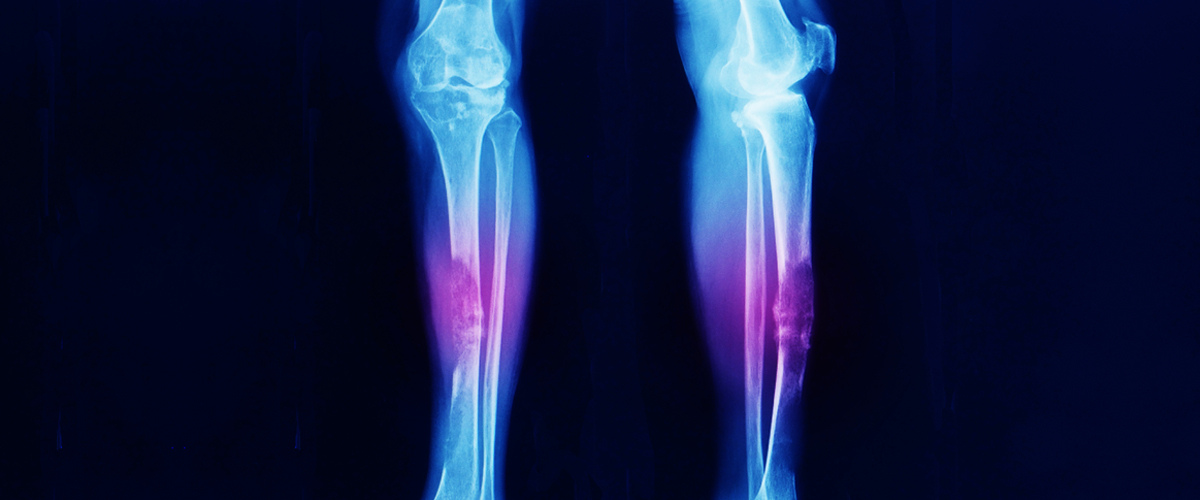

When someone presents to their physician with bone cancer symptoms, such as bone pain, the first step is to get an X-ray. The X-ray would then show us that something is probably going on in the bone. People sometimes ask: Does a bone density test show cancer? It doesn’t.

Then we schedule an MRI to get more detailed imaging, where we can look at the bone and assess the area too. To confirm the diagnosis, we would do a biopsy — when tissue from the bone is removed and examined.

How is bone cancer treated?

Treatment for primary bone cancer varies, but there is almost always surgery to remove the cancer. Depending on the type of cancer, there could be a need for chemotherapy — which works to remove cancer cells — and occasionally radiation therapy, a treatment to shrink tumors

What is important to know in terms of bone cancer detection?

What is helpful to know is bone cancer is almost always associated with bone pain. Bones have a lot of nerve endings in them, so they are sensitive to the changes going on within them. If people are having that persistent, aching pain that is not resolving, visit a doctor and ask for an X-ray. Doing this can help with early detection and improve outcomes.

Wakenda K. Tyler, M.D., M.P.H., specializes in the treatment of benign and malignant tumors of the bones and soft tissues in patients of all ages. As a musculoskeletal oncologist, Dr. Tyler’s practice is focused on the non-operative and operative management of primary soft tissue and bone cancers, sarcomas, and metastatic bone cancer She has written medical journal articles on several bone diseases, the effectiveness of medication in penetrating the site of bone grafts, and the strength of the bone and prosthesis union. Dr. Tyler’s goal is to provide compassionate surgical care that achieves cure of cancer whenever possible by leveraging the latest advances in non-operative management, and minimally invasive and reconstructive surgical techniques.