Understanding Blood Cancer

A leukemia expert explains why blood cancer occurs, common symptoms, how it is diagnosed, and the latest treatments.

In the United States, a person is diagnosed with a blood cancer every three minutes. Leukemia is the most common type of blood cancer in the U.S., and it is the most common form of cancer in children.

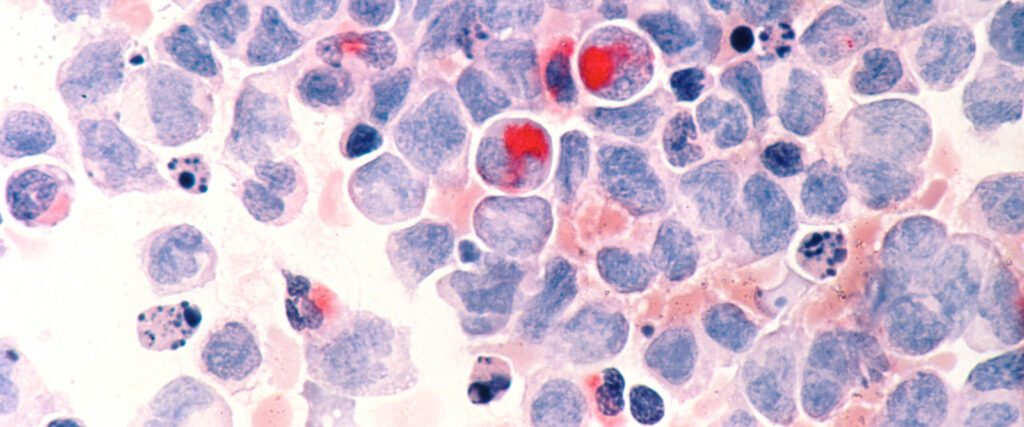

Our bodies are constantly producing blood cells — white cells help fight infection, red cells help carry oxygen, and platelets help with clotting. This process happens in the bone marrow, the soft tissue inside our bones, where very young cells mature before entering the bloodstream to do their jobs. Blood cancer is a cancer of these young blood cells.

“Instead of maturing into a helpful, functional cell, these young blood cells become cancerous and begin to reproduce themselves endlessly,” says Dr. Lewis Silverman, director of the Hope and Heroes Division of Pediatric Hematology, Oncology and Stem Cell Transplantation at NewYork-Presbyterian Morgan Stanley Children’s Hospital of Children’s Hospital of New York.

The cancerous cells begin to “crowd out” the healthy young cells in the bone marrow and then circulate into the blood and travel throughout the rest of the body, he explains.

Health Matters spoke with Dr. Silverman to learn more about the different types of blood cancer, signs and symptoms to watch out for, and what treatments are available.

We often hear about different types of blood cancer. How are they classified?

Dr. Silverman: There are two primary ways we classify leukemias. The first is based on the cell of origin. Our white blood cells fall into two major families: lymphoid cells and myeloid cells. Therefore, leukemia is classified as either lymphoid or myeloid, depending on which type of cell it came from.

The second classification is based on its presentation. A leukemia that appears suddenly and progresses rapidly is called acute leukemia. In contrast, a leukemia that is more slow-moving and might be discovered incidentally on a blood test is called chronic leukemia. These classifications can be combined, resulting in diagnoses like Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (ALL) or Chronic Myeloid Leukemia (CML).

Are certain types more common in children versus adults?

Yes, the vast majority of pediatric cases are acute leukemias. ALL is the single most common cancer diagnosis we see in children and accounts for about 75% of all childhood leukemias. AML is the second most common, making up about 20% of cases.

In adults, you see a mixture of both acute and chronic types. For instance, chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) is a disease of older adults that we never see in children. The reasons for these age-related differences are not yet fully understood, but the pattern is very distinct.

What are the signs and symptoms of blood cancer?

The symptoms of blood cancer can be subtle and easily mistaken for other conditions. Since blood cancers impact the entire body, the signs can be widespread.

Common signs include:

- Fatigue or weakness

- Easy bruising or bleeding

- Unexplained fever that is not caused by an infection

- Unexplained weight loss

- Frequent infections due to a weakened immune system

- Swollen lymph nodes in the neck, armpits, or groin

- Bone or back pain

- Limping due to bone pain

Once leukemia is suspected, how is it diagnosed?

The first step is a simple blood count test. Because leukemia disrupts normal blood cell production, abnormal counts, whether very low or very high, are a key indicator that something is wrong.

To get a definitive diagnosis, however, we must perform a bone marrow test. This procedure involves inserting a small needle into the back of the hip bone, where there is ample supply of marrow. Both a liquid sample and a small solid core sample are extracted. For children, this is a sedated procedure to ensure they are comfortable and still.

Once a diagnosis is confirmed, how is blood cancer treated?

The focus immediately shifts to creating a comprehensive treatment plan tailored to the specific type of leukemia. The treatment of childhood ALL is one of the great success stories of all of cancer therapy. What was once a universally fatal disease now has a very high cure rate, with about 90% of children becoming long-term survivors.

The standard treatment typically involves about 2 to 2 1/2 years of chemotherapy, which kills the cancer cells. While it begins with a hospital stay, most of the therapy is given on an outpatient basis. The chemotherapy is given intravenously (IV), orally, and directly into the spinal fluid via spinal taps (essential because many drugs cannot cross the “blood-brain barrier” to eliminate leukemia cells that may be hiding in the central nervous system). Treatment is given in stages: the induction phase (short, very intense treatment that is administered in the hospital), the consolidation phase (high-dose chemo given over the span of 6 to 12 months as an outpatient), and the maintenance phase (less intensive treatment with the goal to keep the cancer from recurring).

How does treatment for AML differ?

AML requires stronger, higher-intensity chemotherapy, typically lasting about six months. Unlike ALL therapy, this treatment is almost entirely hospital-based, requiring long inpatient stays. Because some patients with AML have a higher risk of relapse, a bone marrow transplant is more often required as part of the initial treatment plan in AML than in ALL. This is a procedure that replaces a patient’s diseased or damaged bone marrow with healthy blood-forming stem cells from a donor. In contrast, with ALL, a transplant is generally reserved after initial treatment, in cases of relapse. The cure rates for AML are also not as high as for ALL, currently standing around 60%.

ALL vs. AML Treatment at a Glance

Duration

Setting

Transplant

Cure Rate

ALL

About 2 to 2.5 years

Mostly outpatient

Reserved for relapse

About 90%

AML

About 6 months

Almost all hospital-based

Part of initial therapy

About 60%

What can someone expect from blood cancer treatment?

Deciding on blood cancer treatment is a shared decision with your oncology team, balancing the cancer type, the health of the patient, and treatment risks. Chemotherapy-based regimens, while incredibly effective, often cause serious side effects like severe fatigue, nausea, and hair loss because it targets all fast-growing cells. Newer, more advanced strategies like immunotherapy, work differently. An example is CAR-T cell therapy, in which a patient’s own T-cells are removed from their body and genetically modified to recognize and target the CD19 protein on B-precursor ALL cells. These engineered T-cells are then reinfused into the patient, where they act as a “living drug,” seeking out and destroying cancer cells. While CAR-T cells have been shown to be effective in relapsed B-precursor ALL, their role in newly diagnosed leukemia is still being studied.

Because immunotherapy activates your immune system, its side effects are different from chemotherapy, often resembling an immune response, such as fever, flu-like symptoms, and fatigue.

Are there also more “targeted” treatments available?

Yes, targeted therapies are another major area of innovation. They work by aiming directly at features that are unique to the cancer cells.

Some examples are:

- Bispecific T-cell engaging (BiTE) antibodies – These antibodies bind to two different targets simultaneously: one target on a T-cell (an immune cell in the body) and another target on a cancer cell. This brings the T-cell and cancer cell together, allowing the T-cell to activate and kill the cancer cell. And example of a BiTE antibody is blinatumomab, which has been shown to be very effective in B-precursor ALL, both at initial diagnosis and at relapse, reducing the risk of subsequent recurrence. Blinatumomab is now used in upfront treatment for nearly all children with B-precursor ALL.

- Antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs) – An antibody is designed to seek out a specific protein on the surface of a cancer cell and is attached to a potent chemotherapy drug. When the antibody binds to the cancer cell, it delivers the chemotherapy directly to its target, minimizing damage to healthy cells.

- Genetically targeted drugs – These shut down the specific genetic abnormality driving a cancer. The best example is in Philadelphia chromosome-positive (Ph+) leukemia. This cancer is driven by a protein called a tyrosine kinase. By using drugs known as tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) with standard chemotherapy, we can block that protein. This dramatically improves outcomes and allows doctors to omit transplant in the majority of patients.

It’s all part of a larger shift: more personalized treatment for blood cancer patients and all cancer patients. Ultimately, the hope is that these more targeted treatment approaches can enhance or even replace some of the standard chemotherapy drugs that are currently used, possibly improving outcomes and reducing side effects of therapy.

Lewis B. Silverman, M.D., is director of the Hope and Heroes Division of Pediatric Hematology, Oncology and Stem Cell Transplantation at NewYork-Presbyterian Morgan Stanley Children’s Hospital and Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons. An internationally renowned expert in pediatric leukemias, Dr. Silverman also serves as the Hettinger Chair in the Department of Pediatrics at Columbia, as well as associate director of pediatric cancers at the Herbert Irving Comprehensive Cancer Center at NewYork-Presbyterian and Columbia.