The Gift: Donating a Kidney to a Stranger

Her chances of finding a match for a kidney transplant were 1 in 100. Here’s how a stranger helped her defy the odds — and how both their lives irrevocably changed.

Hello, Stranger,

When I got the call from my transplant coordinator that I had been matched with you, a 20-year-old woman living on the East Coast, I was overwhelmed with emotion — crying with joy, wonder, and purpose. From that moment, I knew that this kidney was already yours and I am happy for you to finally have it. …

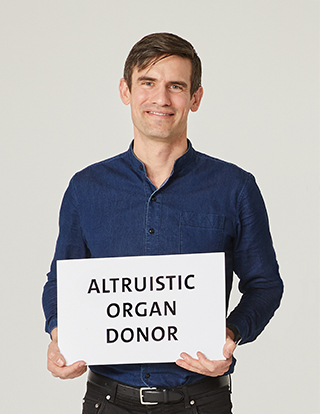

On a chilly November morning in 2019, Hendrik Gerrits was dressed in a hospital gown at NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center with a nervous smile on his face. In his hand, he clutched a letter he had drafted for the young woman who was about to receive his left kidney, which he would anonymously donate in a few hours.

“It’s a little overwhelming to be here,” Hendrik says, his voice shaking. “But I’m very excited. I’ve been thinking about the recipient a lot and hope they’re taking some strength in the idea that we’re in this together.”

Little did Hendrik know, they were not only together in spirit. The recipient was actually on the same floor at NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center.

Down the hall, about 25 feet away, Kali Waters was so giddy about her upcoming kidney transplant she recorded a “happy dance” to post on social media.

“This is it!” Kali declares as she gives two enthusiastic thumbs-up to her mom and grandmother in the room. “I’m receiving a kidney from a complete stranger. I feel like I should be nervous but I’m not. I’m so excited and grateful. I just can’t wait.”

Kali had been through two years of discouraging diagnoses and dialysis treatments. Some doctors told her she should expect to wait for at least seven years for a viable donor, but all that changed when Kali learned about living kidney donation at NewYork-Presbyterian and the hospital’s participation with the National Kidney Registry.

What happened next changed Kali’s life: Her family friend Tracy Kent volunteered to donate a kidney to another recipient when it turned out Tracy wasn’t a match for Kali. That, in turn, unlocked the opportunity for Kali to receive a kidney through the Kidney Paired Donation program at NewYork-Presbyterian. Around the same time, Hendrik, then 37, serendipitously stepped up to be an altruistic kidney donor to someone in need.

What resulted was a successful kidney transplant chain that not only changed the lives of the organ recipients, the organ donors, their families, and countless others. It also formed an unbreakable bond between people who were once strangers and are now linked for life.

Kali: “I Had to Put My Dreams on Hold”

This is, sadly, not the first kidney transplant for Kali Waters.

Kali at age 6.

As an infant, Kali was diagnosed with nephrotic syndrome, a kidney disorder caused when the clusters of small blood vessels that filter waste and excess water from the blood are damaged.

By age 5, Kali started to show signs of renal failure, which meant there was only one solution: Doctors removed both of Kali’s kidneys and started her on dialysis, a treatment in which a machine did the work of a kidney and flushed waste out of her body until a viable organ donor was found. (Most people with renal failure do not need to have their kidneys removed, but in Kali’s case the failing kidneys were causing harmful protein losses.)

For more than a year, Kali was connected to a dialysis machine twice a week at their local hospital in upstate New York. Throughout it all, she was a resilient little girl.

“Kali was such a trooper,” says Louise Clouser, Kali’s grandmother, whom she calls Nana. “She was so young, but she never complained. She took everything as it came without a peep.”

When Kali turned 6, she underwent her first kidney transplant after a match with a deceased organ donor. “I remember waking up with a bunch of tubes around me,” says Kali. “A little scary to experience as a kid, but I was so grateful to go home and happy that I wouldn’t need to be on dialysis anymore.”

Kali Waters

For 13 years, Kali lived a relatively normal life with her new kidney. Besides taking antirejection medication every morning and night and staying hydrated, she was like any other vibrant teen girl.

That changed in 2017. She was halfway through her freshman year of college when she experienced fatigue doing everyday activities like walking from her car to class. Doctors discovered that her body was starting to reject her donor kidney. (Deceased donor kidneys typically remain viable for about 10 to 15 years, according to the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients.)

“They tried to use steroids to help my kidney, but they couldn’t save it,” says Kali. “It was a shock. I was 19. I had just started college and was working. But I knew my world was about to flip upside down.”

Kali was soon back on an arduous dialysis schedule that required her to be at the hospital three days a week for three-hour treatments while juggling classes and her part-time job. She also had to avoid certain foods and limit her intake of potassium, phosphorus, and sodium.

Worse yet, Kali needed another transplant — only this time, finding a match would be incredibly challenging.

Because she already underwent one transplant, Kali developed a high level of antibodies, which meant a higher chance her body would reject a new donor organ. As a result, her doctors predicted that Kali would wait at least six to seven years to find that perfect needle-in-the-haystack match on the deceased donor list.

“It was really disheartening,” Kali recalls. “You don’t want to go through dialysis for a day, let alone years.”

But instead of dwelling on her bleak odds, she was determined to stay optimistic.

“It was definitely a fight every day,” says Kali. “I had to put my dreams on hold and stop going to school. I put all that on the back burner.”

Listen: Kali’s Letter to Hendrik

What do you say to the organ donor who saved your life? Here’s what Kali shared. u003cbru003e

Tracy: “I Stepped Forward to Give Kali the Life She Deserves”

“Share Your Spare. Kidney for Kali.”

Tracy Kent — a longtime family friend whom Kali calls “my role model”— was organizing stacks of bumper stickers to hand out around their hometown in upstate New York.

It was April 2019. Months had passed with no news of a kidney donor, and dialysis treatment was leaving Kali exhausted and exasperated.

She had switched to peritoneal dialysis, which filters waste out of the body via a catheter surgically implanted in the abdomen. The daily treatment required Kali to connect to a machine (or “hook up” as she described it) in her bedroom for at least nine consecutive hours as she slept. While it left her with more flexibility during the day, Kali was tethered to a machine at night.

“I had to be home every night and I couldn’t leave my bedroom once I hooked up,” says Kali. “I wasn’t able to do small things like hang out late with friends or sleep over at their houses. And I was so tired all the time.”

Tracy Kent

Still, “she never complained,” says Tracy. “She has a great spirit.”

And a tenacious one at that. Unwilling to just sit back and wait, Kali sought a second opinion. That’s when a family friend recommended NewYork-Presbyterian.

Kali and her family met with the transplant team at NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center, where Kali learned more about living organ donation. A kidney from a living donor would be more likely to last longer than that from a deceased donor. A living organ donor also meant that Kali likely wouldn’t have to wait as long for a match.

“It was eye-opening,” says Kali. “For the first time in this whole journey, I had a bit of hope that I could get a kidney and not have to wait for years.”

At the urging of her doctors, Kali turned to family and friends on Facebook and shared her story, asking if anyone would consider donating a kidney. While Tracy offered her support, she felt compelled to do more.

“I stepped forward to become a donor so that I could give Kali the life that she deserves,” says Tracy, 50, an elementary school principal and mom to four kids. “I don’t really think there was a question of whether I should do it. Here was this young person who could have her life cut short if she wasn’t able to find a donor, so my heart just said, that’s what you need to do.”

I don’t think there was a question of whether I should donate. Here was this young person who could have her life cut short if she wasn’t able to find a donor, so my heart just said, that’s what you need to do.

Tracy Kent

Turns out, Tracy’s type B blood wasn’t a match for Kali. But giving up wasn’t an option.

NewYork-Presbyterian’s transplant team introduced Kali and Tracy to Kidney Paired Donation, a program that started more than 13 years ago at Weill Cornell Medicine in collaboration with the National Kidney Registry, a nonprofit founded to increase the quality, speed, and number of living donor transplants.

Kidney paired donation allows for two patients who each have incompatible donors to exchange or swap donors with each other in order to get the perfect match.

“Paired kidney exchange has afforded an opportunity to people with incompatible donors that didn’t exist before,” says Marian Charlton, who was the chief transplant coordinator at NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center and helped Tracy through the process. “Now, every kidney transplant candidate with an incompatible but willing and approved donor can receive a living donor kidney transplant.”

“Tracy and I have always been really close,” says Kali. “I’ve always looked up to her, and the fact that she’s donating, that just makes me look up to her even more. I’ll always be grateful to her.”

In August 2019, Kali and Tracy joined the National Kidney Register database along with other hopeful donor-recipient pairs. Then they waited — and prayed for a match.

Listen: Tracy’s Letter to Her Anonymous Recipient

Tracy didn’t know his name, but she knew she wanted to help someone in need.

Hendrik: “I Felt Grateful I Could Have an Impact”

Hendrik Gerrits remembers sobbing on the subway when he learned about living organ donation.

It was late fall in 2016, and he was on his regular commute from the Museum of Arts and Design in Manhattan, where he is the deputy director of exhibitions and operations, to his home in Ridgewood, Queens.

As he sat on the L train listening to the podcast Risk!, he found himself struck by the story of a woman who became a nondirected kidney donor to help one stranger. She ended up jump-starting a transplant chain that saved the lives of 28 recipients.

“I just remember bawling,” recalls Hendrik. “I was overwhelmed by the power of the story — and I immediately thought, I could do that.”

Hendrik Gerrits

As a long-distance runner and avid rock climber, Hendrik was a prime candidate to be a living kidney donor. “I’m fortunate to say I’m healthy,” he says. “And I immediately felt grateful that there was something I could do in the world that would have such a huge impact.”

The need for kidney donors far outpaces the demand for any other organ in the U.S. Currently, almost 109,000 people are on the national organ transplant list; of those, roughly 92,000 are waiting for a kidney, according to the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network. In 2019, about 29% of kidney transplants performed in the U.S. stemmed from a living donor, and less than 2% of kidney transplants came from altruistic donors (also referred to as nondirected donors).

In January 2019, Hendrik told his wife, Lumin, that he had reached out to the National Kidney Registry to become an altruistic kidney donor.

“I’m really lucky to have a wife who doesn’t blink at any crazy old thing I want to do,” says Hendrik, who is also dad to daughters Liv, 6, and Frida, 2. “She said, ‘Well, I support you, and I hope your karma rubs off on me!’”

Two questionnaires, a urine screening, and a blood test later, the National Kidney Registry connected Hendrik with the transplant team at NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center. As a donor, Hendrik learned he would undergo a minimally invasive procedure to remove his kidney. Following his surgery, outside of fatigue and limited physical activity for a couple of weeks, Hendrik could return to running, climbing, and lifting his daughters about a month after his organ donation.

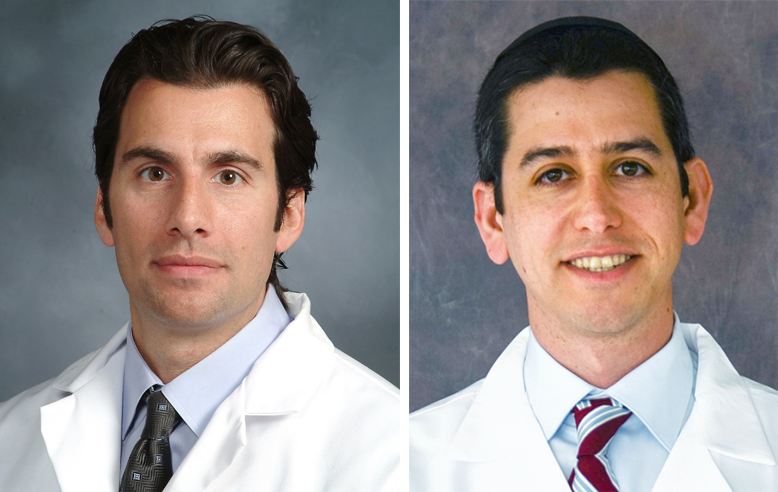

“The remaining kidney is going to grow in function, almost like working out and becoming more effective at what it does,” says Dr. Joseph Del Pizzo, urologist and living donor surgeon at NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center and Hendrik’s surgeon. “It should not adversely affect the rest of his life in any way.”

Hendrik only sees how his life will change for the better.

“One reason I’m doing this is to set an example for my daughters,” says Hendrik. “We used a pillow in the shape of a kidney to explain what the organ is and why I was giving mine to someone in need.”

He also wants to inspire more people to become kidney donors. “Most people I talk to don’t even know that this is an impact you can make,” Hendrik says. “You have two kidneys and you only need one. The power of the extra one is that it can allow someone to live a whole new life.”

Listen: Hendrik’s Letter to Kali

Find out why Hendrik calls his altruistic organ donation “a new beginning.”

A “Miracle Match”

On a rare night out for dinner in October 2019, Kali received life-changing news: A match had been found for both Kali and Tracy — and their surgeries had been scheduled for the following month. Instead of waiting seven years for a donor, seven weeks had passed since Kali joined the Kidney Paired Donation program.

“The first thing I felt was shock,” says Kali. “All I know about my donor is that he’s a 37-year-old male and he is just donating to donate, which is awesome.”

Hendrik was equally overwhelmed when, just three weeks after completing blood work and paperwork, he heard that a young woman would be receiving his kidney. “It’s weird,” says Hendrik. “I feel rather attached to this person whom I’ve never met before.”

Maybe that’s because it seems as though Hendrik and Kali were destined to connect. When reviewing their medical records, doctors discovered “she did not have one antibody against him,” says Charlton. “I call it a miracle match.”

Because of Hendrik’s altruistic organ donation, a transplant chain developed that linked Tracy’s kidney to Tom Morales, a father of two in Denver who had been waiting over two years for a new kidney.

Tracy was a match for Tom Morales (left, with his son, Thomas; his daughter, Alyssa; and his wife Angie) who had been on dialysis for two years.

“Hendrik is a very heroic guy,” says Dr. Del Pizzo, who is also the E. Darracott Vaughan, Jr. Professor of Urology and director of laparoscopic and robotic surgery for the Department of Urology at Weill Cornell Medicine. “Through this selfless act, he isn’t just helping Kali and Tom. Everyone on the transplant waiting list is going to move up the list and get one step closer to getting a kidney. So, he’s really helping thousands of people.”

Kali’s family echoed the sentiment. “It’s phenomenal what this man did,” says Louise. “We call him ‘Mr. Wonderful.’”

Inside the Kidney Transplant

“Today, I get a new kidney!” Kali practically squealed as she was wheeled toward the operating room at NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center around 7 a.m. on November 19, 2019. “I’m already thinking about all the foods I’ll be able to eat when I wake up!”

Hendrik was waiting down the hall with his mom by his side and his daughters’ purple kidney pillow resting on his lap. He would soon head into an operating room close to Kali’s.

The three-hour transplant started when Dr. Del Pizzo removed Hendrik’s left kidney laparoscopically through a 3-inch incision in the belly button. Dr. Del Pizzo then placed the kidney into a surgical basin filled with iced saline solution and carried it to Kali’s operating room, where Dr. Samuel Sultan, transplant surgeon at NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center, was waiting to implant Hendrik’s kidney in Kali.

The transplant team: Dr. Joseph Del Pizzo (left) and Dr. Samuel Sultan performed the kidney transplant between Hendrik and Kali.

“Many times when we do a living donor kidney it works right away. We say it ‘pinked up,’” says Dr. Sultan, referring to the color of the donor kidney when blood starts circulating through it. In Kali “it pinked up within seconds. That means everything was working nicely.”

Tracy’s kidney had to travel a bit farther — 2,000 miles, to be exact. That same morning, Tracy’s left kidney was removed at NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center as well. The organ was then packaged by a transplant team from LiveOnNY and flown to UCHealth, where Tom was waiting for his transplant later that afternoon.

The change in Kali was apparent several hours later in the recovery room. “I automatically felt better,” she says. “Before, I would wake up and I wouldn’t feel good. After surgery, I just woke up and I was like ‘whoa!’ It felt like a new me.”

The best news of all? “She has no chance of needing dialysis any time soon,” says Dr. Sultan, who is also assistant professor of surgery at Weill Cornell Medicine. “It’s heartwarming to see someone so young get their health back in order and get a new chance in life.”

Meeting “Mr. Wonderful”

Two days after their transplant surgery, Hendrik and Kali have agreed to meet.

Kali is sitting in a common room at NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center, her once pallid complexion now flush with excitement. She’s seated with her mom and Nana, all three craning their necks to scan the hallways for “Mr. Wonderful.”

“I feel like I’m more nervous to meet him than I was to have the actual surgery!” Kali says.

After a few minutes, Kali spots Hendrik’s lean frame coming toward the door and gingerly stands up. With big smiles and tears in their eyes, Kali and Hendrik laugh as they greet each other with a long hug.

“How are you?” Hendrik asks. “It’s so good to meet you.”

“I’m feeling really good!” Kali replies. “My doctors said they’ve never seen a kidney work so quick.”

“I took good care of it,” Hendrik says. “My kidney gets to hitchhike in a body that’s half my age. I’m sure it’s thrilled.”

With family members looking on, Hendrik and Kali sat and talked about Hendrik’s daughters and his family’s upcoming holiday plans as well as Kali’s desire to go back to school to study finance and how different life already looks.

Hendrik gave me my freedom back. A lot of people don’t know that this kind of altruistic donation is even possible, but it can change someone’s life drastically.

Kali Waters

“Before, I would want to take a nap all the time. Now I want to get up and go for a walk,” Kali says. “And I got to eat a banana — something I haven’t been able to eat in two years!”

In between exchanging stories, they often pause to look at each other in disbelief that they are sharing this moment.

“I just think this is so cool,” says Hendrik. “I’m so happy for you. It sounds like you have so much ahead of you.”

“I have a whole new life ahead of me. You don’t even know how … ” Kali suddenly chokes up. She pauses to collect herself before she looks up at Hendrik and simply says through tears: “Thank you.”

Before saying good-bye, Kali shared a letter she had written to Hendrik before her surgery, and they promised to keep in touch.

The day before Hendrik and Kali’s big meeting, Tracy received a call from an unfamiliar Colorado area code. She, too, had written a letter to her recipient, Tom, before surgery “in hopes that he would one day want to connect,” Tracy says. “I never imagined he’d call me the day after his surgery.”

Tom, 52, had been on dialysis for two years before receiving Tracy’s kidney.

“I couldn’t walk far without breathing heavily,” he says. “I couldn’t do simple things like mowing my lawn, driving long distances, doing household chores … I’d lose focus and would get tired very quickly.”

When he heard he was getting a kidney, he couldn’t believe it.

“I had prayed that I would get to know who my donor was,” says Tom. “I wanted to at least thank her for what she had done for me. It was incredible to be able to speak with the person who’s given me my life back. I told her how brave she was to do this.”

Hendrik, Kali, and Tracy reunited with their respective families in New York City in February 2020, just weeks before the coronavirus outbreak hit the city.

Chain Reaction of Gratitude

Kali is taking silly selfies with Hendrik’s daughter Liv as Hendrik chats with Nana about a cruise she took soon after Kali’s operation. Nearby, Tracy and Lumin play with little Frida.

Three months after the kidney transplant, Hendrik, Kali, and Tracy, plus their family members, have come together for a photo shoot in New York City, just before the COVID-19 pandemic shut down much of the nation.

Before their reunion, Hendrik and Kali texted often and occasionally caught up on FaceTime over the holidays “just to see how each other is doing, not just physically, but emotionally, as well,” says Kali.

Hendrik and Tracy stayed connected too. “Because we have a shared experience, it’s been really nice to be able to communicate with someone who really gets it,” says Tracy.

“I think about them a lot,” Hendrik says of Kali and Tracy. “Every now and then I’ll send a text to say hello or a picture of my kids.”

Hendrik marvels at how quickly he recovered, even after a rare complication that was quickly addressed. Sixteen days later he was back to running, and within six weeks of the transplant, he was back to rock climbing. In April, however, he contracted the coronavirus.

“Recovering from COVID was significantly harder than recovering from the transplant!” says Hendrik, who is finally back to logging long daily runs.

Kali has since returned to work at a physical therapy office and “doing normal 22-year-old things,” says Kali, who still receives her follow-up care at NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center. “It’s like night and day. I don’t have any pain, which is incredible.”

“Kali is doing exceedingly well,” says Dr. Sultan. “It’s truly remarkable that we found such a close match and that an altruistic donor helped give her back her life.”

Organ transplants cross racial divides, social divides, political divides. It’s such a visceral reminder of how we really are completely the same. That is a gift.

Hendrik Gerrits

Because she received a living donor organ, Kali can expect her new kidney to last nearly 20 years. “Hopefully even longer in her case because of the good match, the excellent health of the kidney, and knowing that Kali will continue to take great care of it,” adds Dr. Sultan. “There are also always new technologies coming out and new medications that are being developed. We hope as time evolves, kidney transplants will last longer.”

Kali, however, is focused on being grateful for what she has now. “Hendrik gave me my freedom back,” she says. “A lot of people don’t know that this kind of altruistic donation is even possible, but it can change someone’s life drastically. I’ll never forget this gift of life that he’s given me.”

By sharing his experience, Hendrik hopes more people will consider living organ donation to extend that gift to many others. “Organ transplants cross racial divides, social divides, political divides. It’s such a visceral reminder of how we really are completely the same,” says Hendrik. “Everyone should have the chance to live — and to live a full life.”

To learn more about becoming a living organ donor, visit nyp.org/organdonor.