Taking Steps to Solve the Organ Transplant Crisis

Dr. Megan Sykes is leading cutting-edge research designed to reduce the occurrence of rejection in organ transplant recipients.

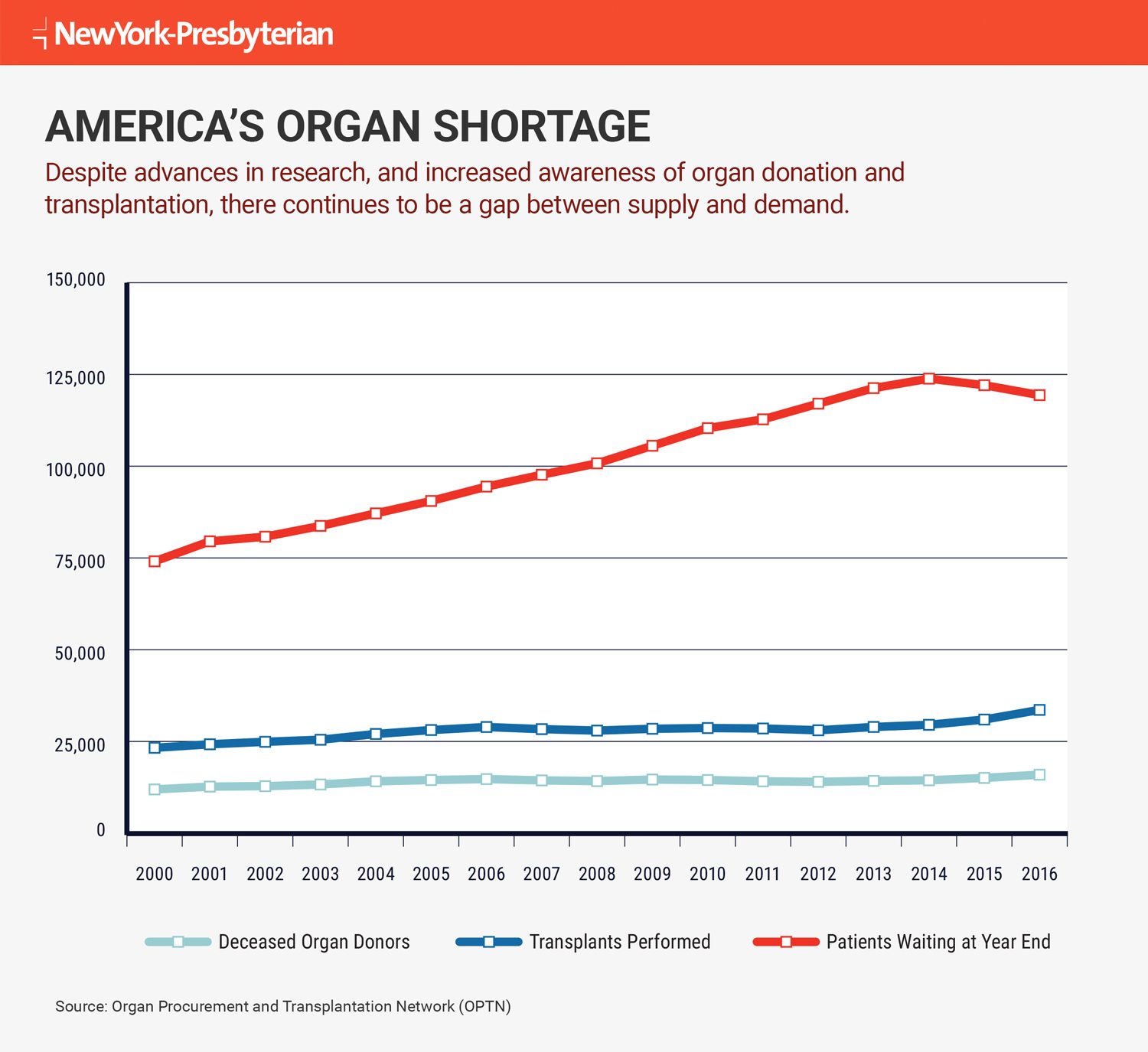

Last year, 33,600 organ transplants were performed in the U.S. compared with 28,000 in 2012, a 20 percent increase in five years. That sounds like a success, with more organs available for patients who need them.

But the numbers don’t tell the whole story.

Many patients who receive an organ run into complications years after their surgeries, says Dr. Megan Sykes, director of the Columbia Center for Translational Immunology at NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia University Medical Center, and professor of microbiology & immunology and surgical sciences (in surgery) and the Michael J. Friedlander Professor of Medicine at Columbia University Medical Center.

“All the improvements in immunosuppressant drug therapies [drugs that prevent transplanted organs from being rejected by the recipient] have led to better survival rates in the first one to two years,” she says. “But beyond that, there’s a process of slower graft loss, known as chronic rejection, where the organs get rejected down the line.” And despite advances in medicine and technology, “those late graft loss rates have not improved,” says Dr. Sykes.

Though the statistics on organ rejection differ widely depending on the procedure and type of organ, only 54 percent of kidney transplants, Dr. Sykes’ primary area of focus, are still functioning 10 years later, according to the National Kidney Foundation.

A Growing Pool of Patients in Need of Organs

Just as problematic, people in need of a second transplant due to that late graft loss tend to have even more sensitive immune systems than initially, which means their bodies are primed to reject the new transplant immediately.

“You can see how this cycle compounds the need for organs and worsens the organ shortage,” Dr. Sykes explains. Indeed, every 10 minutes, a person is put on the national transplant waiting list, adding to the more than 118,000 Americans who need an organ. And every day, an average of 22 people die while waiting for one, according to the United Network for Organ Sharing.

To help tackle this crisis and the suffering it creates for patients and their loved ones, Dr. Sykes and her colleagues at the Columbia Center for Translational Immunology (CCTI) at Columbia University Medical Center are conducting cutting-edge research they hope will change the long-term outlook for transplant patients without the use of potentially toxic, lifelong immunosuppressant drug therapy.

In the short term, these anti-rejection drugs can be lifesaving, working to suppress the immune system to prevent organ rejection. But they can also predispose patients to deadly infections and cancer. They may also lead to bone loss, cataracts, hypertension, diabetes, and kidney failure.

Yet right now, these potent medications are pretty much the only option doctors and patients have.

“The ethical bar for stopping immunosuppression and trying something else is set pretty high,” says Dr. Adam D. Griesemer, assistant professor of surgery in the Division of Abdominal Organ Transplantation at NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia University Medical Center and principal investigator at CCTI. “We’d be risking that patients lose an organ necessary for survival — a heart, lung, or liver — so it hasn’t been attempted in these organs yet.”

These challenges are why the team at CCTI is doing preclinical research on mice and larger animals that focuses on inducing immune tolerance, a state in which the body sees the donated organ as part of itself rather than as a foreign object, and thus doesn’t reject it.

“The primary goal of our research is to get people to accept the graft the first time, without all the immunosuppressant drugs. That’s number one,” says Dr. Sykes. “And number two is to not contribute to that growing pool of patients who need retransplantation — the patients it’s tough to find a suitable donor for.”

Using Bone Marrow to Make Transplants More Successful

Most people think of bone marrow transplants as a treatment for people with blood diseases like leukemia or aplastic anemia. But in studies of both patients and animals receiving donor bone marrow cells along with a new kidney, Dr. Sykes and her team have shown that marrow can influence the recipient’s immune cells to induce tolerance.

Dr. Griesemer explains how the multistep process works with kidney transplants in animals: A week or two before the transplant, the recipient gets treatment meant to deplete a portion of its bone marrow “to make space for the donor cells to engraft,” he says. The recipient is also infused with antibodies that attack and deplete T-cells and B-cells, which normally drive the body’s immune response.

Then, on the day the new kidney is transplanted, stem cells from the donor’s bone marrow are extracted and infused into the recipient. The new bone marrow cells appear to dampen immune response to the new organ.

“The new bone marrow,” says Dr. Griesemer, “prevents the development of new immune cells that ordinarily would respond to and reject the organ.”

Advances in Preventing Organ Rejection

Dr. Sykes began this research at Massachusetts General Hospital, the teaching hospital of Harvard Medical School, in the early 1990s. As associate director of the Transplantation Biology Research Center, she was involved in the world’s first successful bone marrow studies that intentionally induced immune tolerance in patients — not mice — with transplanted kidneys.

“Most patients never come off immunosuppressant drugs,” says Dr. Griesemer. But the first patient to receive this treatment at Massachusetts General has survived for almost 15 years, 14 of those without immunosuppressant medication. Six other of Dr. Sykes’ patients also accepted their kidneys for more than five years without immunosuppressant drugs, although three eventually returned to a low level of medication. All of these patients still have their original donor kidney.

Dr. Sykes has been expanding on this work since 2010, when she moved from Harvard to NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia University Medical Center, where she collaborates with the kidney team, among other departments, and also meets regularly with the kidney transplant team at NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center and Weill Cornell Medicine. The goal: to improve on the immune tolerance approach she developed at Harvard and make it applicable not just to kidney transplants but also to harder-to-replace organs like the heart and liver.

“With this research, we are getting much closer to patients not having to take these drugs after a transplant. We’re poised for the next breakthrough.”— Dr. Adam D. Griesemer

“We’re working on getting the new bone marrow cells to persist a lot longer in recipients by combining it with a special type of T-cell that suppresses the immune response,” Dr. Sykes explains. “We are also expanding our work to lung transplantation.”

Her team hopes to begin trials with patients in need of a new kidney in the next two years; heart and lung transplants are further down the road. “With the kidney, we are able to begin the tolerance induction process before the organ transplant since living donor kidney transplants are common,” says Dr. Griesemer. “But it’s impossible to do that with these other organs, because we don’t know when they will be available.”

To get closer to the goal of being able to transplant a heart, lung, or liver first, before inducing immune tolerance, the CCTI team is generating “suppressor cells” to dampen the immune response. Researchers are producing these cells by taking them from recipients well before the transplant, multiplying them in petri dishes in the lab, then freezing them. They’re then given to animals that have received a transplant. Some of this research is being done in large animals, which have an immune response that is more similar to humans than mice.

“The trick is to suppress the immune response and prevent the development of new immune cells that might reject the organ,” says Dr. Griesemer.

A Natural Fit for NewYork-Presbyterian

Dr. Sykes explains what prompted her to join NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia University Medical Center.

“For me, the big draw in coming here was the size and scope of the organ transplant program. It’s one of the biggest in the country,” she says. To that program, Dr. Sykes has added the Columbia Center for Translational Immunology. “It’s more than a transplant program,” she says. There are now 100-plus people doing work that covers not just transplants but also basic human immunology as well as research on cancer immunotherapy and autoimmune diseases. “With all of it,” says Dr. Sykes, who has recruited 15 faculty members, each with their own team of researchers, “the goal is improving the treatment of immune-related diseases in humans.”

Dr. Sykes and her team are also exploring the possibility of using organs from other species in human patients, which, she says, would drastically cut down on the waiting time for organs from human donors. Tissue from pigs and cows has long been used for heart-valve replacement in people, but transplanting organs from animals to humans is much more challenging. The immune response to organs from another species — known as a xenograft — tends to be even stronger than with a human-to-human transplant.

To that end, the researchers have again been working with bone marrow to try to induce immune tolerance that would allow organs from one species to another to be accepted. “The animal research is moving us quickly toward our goals,” says Dr. Sykes.

Dr. Griesemer says he’s optimistic about the near future. “Every transplant patient is very thankful after surgery, but they all eventually ask when they can get off the immunosuppressant drugs — the side effects wear on them,” he says. “With this research, we are getting much closer to patients not having to take these drugs after a transplant. We’re poised for the next breakthrough.”

That progress, the kind that translates into patients leading full, healthy lives with donated organs, is exactly why Dr. Sykes says she entered the field.

“This work has been incredibly satisfying in terms of my scientific interests, but also for my medical experience,” says Dr. Sykes. “I’ve been fascinated and troubled by the challenges with organ transplantation in patients — the clinical problems are huge,” she acknowledges.

But, she adds, “there’s so much promise in this work, both in terms of achieving immune tolerance in transplant patients and, eventually, overcoming the organ shortage. I’m very excited about it.”