Should You Have Your Fallopian Tubes Removed to Prevent Ovarian Cancer?

An expert explains why removing the fallopian tubes during another pelvic surgery could reduce your risk of getting this cancer.

Recently tennis legend Chris Evert, who had undergone treatment for stage 1 ovarian cancer two years ago, announced that doctors had found a recurrence of cancer in her pelvic region. “My cancer is back,” Evert said in a statement. “While this is a diagnosis I never wanted to hear, I once again feel fortunate that it was caught early.” Evert has a family history of ovarian cancer and had learned in 2021 that she had a variant of the BRCA1 gene, which puts her at higher risk for ovarian and breast cancer.

According to estimates from the American Cancer Society, about 20,000 people in the U.S. will be diagnosed with ovarian cancer this year, with more than 13,000 projected to die from the disease. Ovarian cancer is the fifth-leading cause of cancer deaths in women — more than any other female reproductive cancer.

So how can women lower the risk for ovarian cancer? Several leading medical groups recommend that women who undergo pelvic surgeries should also consider having their fallopian tubes removed at the same time if they are finished having children.

The guidance builds on research that shows that many ovarian cancers begin in the fallopian tubes. According to the Ovarian Cancer Research Alliance, which issued its recommendation for the preventive surgery in 2023, 70% of the most common and lethal ovarian cancers begin in the fallopian tubes.

“We don’t have good screening tools for ovarian cancer. Therefore, we don’t have a way to diagnose the disease early,” says Dr. Jason Wright, chief of the Division of Gynecologic Oncology at NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving Medical Center. “That makes strategies for prevention welcome.”

Dr. Jason Wright

Dr. Wright explains why this preventive surgery, called opportunistic salpingectomy, is being recommended and what it entails for women and gender non-conforming people born with ovaries.

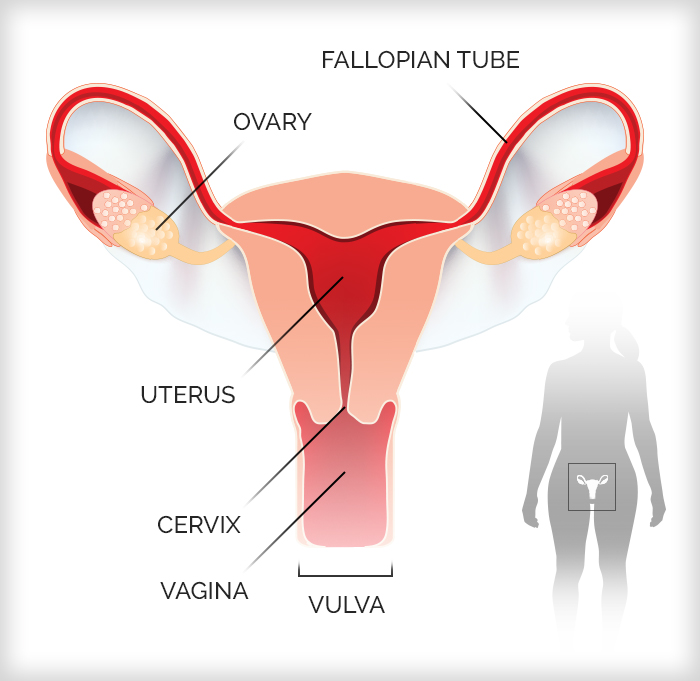

What are the fallopian tubes, and what is their role in ovarian cancer?

The fallopian tubes are the tubular structures that connect the uterus to the ovaries. At the time of ovulation each month, the fallopian tubes essentially transport the egg, or ovum, into the uterus.

We have historically assumed that ovarian cancers begin only in the ovaries. But there’s epidemiologic evidence now that most cancers of the ovary actually start in the fallopian tube.

Is this approach of preventative removing fallopian tubes a new one?

The Ovarian Cancer Research Alliance recommended the practice in 2023 for those already having surgery for noncancerous conditions including hysterectomies, cysts, endometriosis, and tubal ligation (in which the fallopian tubes are cut, tied or blocked to prevent future pregnancies). In recent years, two major medical groups, the Society of Gynecologic Oncology and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), also have supported removal of the fallopian tubes when performing some pelvic surgeries for patients who have completed childbearing or decided to not have children. Women also can choose to have their fallopian tubes removed, in lieu of tubal ligation, during a cesarean section.

What are the recommendations for those at high risk for ovarian cancer, such as people who carry a BRCA gene mutation, like Chris Evert?

The recommendations are different for those who have a significant risk of ovarian cancer, such as those who carry genetic mutations like BRCA1 and BRCA2. They are advised to undergo removal of both the ovaries and the fallopian tubes and sometimes the uterus. Doctors recommend having this surgery even if you aren’t already having another gynecologic surgery. These patients will stop having periods and will go into menopause.

How effective is removing the fallopian tubes in preventing ovarian cancer?

A recent study showed that cases of ovarian cancer were significantly lower among a group of individuals undergoing opportunistic salpingectomy compared with people in a control group who didn’t have their fallopian tubes removed. Epidemiologic data suggests that the strategy is effective, and I’m very hopeful that we will succeed in lowering ovarian cancer rates.

How do doctors perform the procedure, and how safe is it?

The fallopian tubes are cut from the uterus and the ovaries and then removed. We would use the same surgical approach as for the gynecologic procedure the patient is already undergoing. These surgeries are often done laparoscopically with minimally invasive surgery, which is associated with a lower risk of infection and a quicker recovery.

Studies have shown that removing the fallopian tubes adds very little to the risk of complications. It may add a few minutes of operating room time. But it is a safe and straightforward procedure when performed at the same time as another gynecologic surgery.

Many doctors have already been recommending this for their patients, and it has gradually diffused into clinical practice in recent years.

Dr. Jason Wright

What is the recovery time?

The procedure itself adds very little additional time to recovery. The recovery time is generally based on the primary surgery performed, such as the hysterectomy, and not the fallopian tube removal.

Will you still have periods after this procedure and can you get pregnant?

It depends on the primary surgery you’re having. Having your fallopian tubes removed won’t stop you from having periods. So, for example, if you have the fallopian tubes removed to prevent future pregnancies, your periods would continue until you are postmenopausal. A hysterectomy eliminates bleeding associated with periods, regardless of whether the fallopian tubes are taken out.

Once the fallopian tubes are removed, you can’t have children.

Researchers have studied whether removing the fallopian tubes impairs ovarian function, and the data shows that it doesn’t. Importantly, the ovaries continue to produce beneficial hormones even after removal of the fallopian tubes, helping to protect you against heart disease and osteoporosis.

Jason Wright, M.D., is chief of the Division of Gynecologic Oncology at NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving Medical Center and vice chair of academic affairs in the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons. He is editor-in-chief of Obstetrics & Gynecology and a nationally recognized expert in gynecologic surgery and the treatment of gynecologic cancers. A major focus of Dr. Wright’s work is the delivery of quality care and the improvement of outcomes of women with cancer and those who undergo surgery. His clinical research focuses on the evaluation of novel therapeutics, targeted therapies, and biologic treatments for gynecologic cancers.

Additional Resources

Learn more about gynecologic cancer care and women’s health at NewYork-Presbyterian.