Long COVID: Patients Experience Symptoms One Year Later

One year into the pandemic, patients’ lives have been upended by long COVID. An expert explains what researchers are doing to understand and treat it.

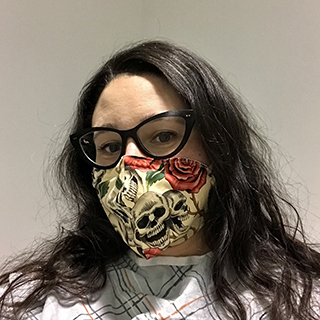

Elizabeth Yuko, before the pandemic, in the spring of 2019. Credit: Karen Novak

Elizabeth Yuko was mid-lecture when she suddenly lost her train of thought. Her PowerPoint presentation on bioethics sat open on her laptop, yet she stared at it blankly. She let a few more moments pass until asking one of her students over Zoom to remind her where she left off.

This loss of concentration has become a normal occurrence for Elizabeth. A bioethicist, adjunct professor of bioethics at Fordham University, and freelance journalist, she is also a “COVID long-hauler,” who continues to experience a myriad of symptoms since she became sick with COVID-19 one year ago.

Elizabeth lives with daily fatigue and has difficulty concentrating and finding the right words, symptoms of what has become known as COVID brain fog. On top of that, she’s also struggled with severe headaches, stomach issues and more perplexing symptoms like persistent pinkeye, hair loss, joint pain and body aches, unreliable depth perception where she loses her balance and bumps into furniture, and symptoms similar to dyslexia.

“Everything from letters and numbers moving around and switching places to making weird, very easy typos and mistakes,” says Elizabeth, 37, who lives in Queens, New York, and is a patient at NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving Medical Center.

A year into the pandemic and her illness, Elizabeth is not unique in continuing to battle prolonged symptoms. Researchers estimate that 10% to 30% of people infected with the coronavirus experience long-term waxing and waning symptoms, and some didn’t feel sick at all when they were initially infected.

One study in The Lancet found that at six months after getting COVID-19, more than 60% of patients who had been discharged from a hospital reported fatigue, more than 25% reported difficulty sleeping, and more than 20% reported anxiety or depression. “Those are strikingly high numbers,” says Dr. Lawrence Purpura, a postdoctoral clinical fellow in clinical medicine in the Division of Infectious Diseases at Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons and an assistant attending physician at NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia.

Clinic treats long COVID patients

Dr. Purpura was working shifts treating COVID-19 patients while his wife was doing the same in an emergency department at another hospital when the Division of Infectious Diseases at NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia launched a study to learn all they could about the disease in March 2020.

Dr. Lawrence Purpura

Since then, Dr. Purpura; Dr. Michael Yin, the study’s senior investigator and an infectious disease expert at NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia; and their colleagues have collected specimens such as blood, saliva and stool samples, and in some cases breast milk or semen, from more than 250 participants to test for patients’ immune response, viral persistence, and long-term complications. PCR testing and genetic sequencing of the virus are also in the works. “We wanted to collect quality data and biologic specimens to study how the SARS-CoV-2 virus impacts the body and immune system, particularly over time,” says Dr. Purpura.

Months into the study, researchers found that many of these patients were still reporting symptoms: 61% of those who had mild cases of COVID-19 and 69% of severe cases reported at least one long COVID symptom.

These “shockingly high numbers” inspired Dr. Purpura to establish a comprehensive long COVID clinic at NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia to provide services and support for people coping with long COVID. The clinic evaluates patients, including full workups with blood work, echocardiograms, EKGs, and other screenings. It also connects them with specialists like cardiologists, psychiatrists, and neurologists to treat specific symptoms and collaborate on patient care. “We want to be able to provide the best care we can to patients who are experiencing this phenomenon,” says Dr. Purpura.

The clinic has been up and running since January and is seeing patients — including Elizabeth, who has periodic telehealth appointments and is seeing a neurologist. Like Elizabeth, most of the clinic’s patients and those in the study reporting long COVID symptoms were not hospitalized when they contracted the disease, Dr. Purpura notes.

“Many are relatively young, healthy people who were not hospitalized and who recovered at home,” says Dr. Purpura. “Clearly there’s a very high rate of complications in our patients and our community, even among those who had mild initial illnesses.”

More than anything, it (the long COVID clinic) made me feel normal at a time when everything in my life had been abnormal for months.

Elizabeth Yuko

Determined to find answers

The idea of complications occurring after a viral infection is not new, explains Dr. Purpura. “The truth is that it’s something that can be expected after certain viral infections.” With post-Ebola syndrome, for example, which Dr. Purpura has studied among Ebola survivors in West Africa, some people experience long-term fatigue, joint pain, headache, hair loss, and an eye condition called uveitis, which can lead to vision loss if left untreated.

The most common long COVID symptom is fatigue. Long-haulers also report neurologic problems like the brain fog Elizabeth experiences and shortness of breath, cough, intermittent fever, joint pain, chest pain, diarrhea and gastrointestinal issues, and skin rashes, along with anxiety and depression, chest pain, and other cardiac complaints. Among them, “Cardiomyopathy and pericarditis and myocarditis have been well-described in the acute phase [of COVID],” Dr. Purpura says. “Although rare, these problems can persist for several weeks to several months, especially if a patient goes on to develop heart failure or arrhythmias.”

Fast heart rate is another cardiac symptom some patients experience. Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome, or POTS, “can result in a fast heart rate, lightheadedness, or even passing out in very severe cases,” he says.

While there aren’t treatments for long COVID, there are healthy habits that can help alleviate some symptoms; for example, establishing a regular sleep routine can help with insomnia, which is known to exacerbate other symptoms like chronic fatigue and feeling generally unwell. However, for the more unusual cardiopulmonary and neurological symptoms, Dr. Purpura says, more research is needed to know what treatment options will be effective.

What makes long COVID complicated is its novelty — scientists and researchers are still working to understand it. At the start of the pandemic, doctors and nurses were just trying to treat the surge of patients; now, more than a year later, the medical community is grappling with the increasing number of long-haulers and how best to care for them. More studies like the one at NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia are underway to learn what drives these symptoms and why certain people are more prone than others.

Dr. Purpura and other researchers have theories about what’s behind these perpetuated symptoms. “[When it comes to brain fog] we suspect that there may be some sort of underlying inflammatory response after their acute illness,” he says. “There are other hypotheses, including an autoimmune-type syndrome or low-level persistence of the virus. We just don’t know yet.”

In addition to researching the factors that contribute to the lingering symptoms, “We are doing work in other key areas: characterizing the risk of reinfection and understanding how COVID-19 vaccines impact the clinical and immunological course of the disease in these long COVID patients,” says Dr. Magdalena Sobieszczyk, chief of infectious diseases at NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia and associate professor of medicine at Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons. “Importantly,” she adds, “we are working to learn about the contribution of environmental, familial, household, and community-level factors on the clinical outcomes in patients who live with long COVID. There is much to learn in these areas, and we are taking an integrated and very comprehensive approach.”

Struggling to adapt to a new normal

Elizabeth’s first sign of COVID-19 began on April 2, 2020, with a sore throat that soon led to severe shortness of breath, fever and night sweats, persistent dry cough, headaches, diarrhea, and debilitating fatigue for nearly a month. It was at the height of the pandemic in New York City, when the city’s hospitals were struggling to keep up with the influx of COVID-19 patients. She heeded doctors’ advice to stay home and recover in her 469-square-foot apartment.

Elizabeth waiting for a chest x-ray.

“I’ve never been so thankful for having a space this size, because I would be winded walking the four steps from my bed to the bathroom,” she says. Still, she would rally herself to walk to her window to cheer at 7 p.m. for the city’s healthcare workers. “Some days I could clap for 20 seconds before being completely out of breath and ready to collapse,” says Elizabeth. “Some days it was a struggle to get off the couch at all.”

While she can now walk down to her apartment building’s lobby to retrieve her mail without getting winded, Elizabeth still has constant fatigue and brain fog that have lingered for a year now. These symptoms aren’t just daily nuisances for her. They impact her work as a professor and journalist. “All I do is use my brain, so it really is not conducive to the work that I do,” says Elizabeth, who has constant deadlines. “It’s very difficult to deal with this fatigue — I’m always tired, and there are times when I just need sleep for two hours but then fall behind on things.”

As if the never-ending symptoms weren’t enough, from the end of April to December 2020 Elizabeth experienced what she calls relapses. “I always had a certain level of fatigue, brain fog, and some digestive inconvenience,” she says. “But then I’d go through periods every two to four weeks where my symptoms would get much more intense, and it would be similar to the symptoms that I had when I first had COVID.”

The signal was unmistakable: If she woke up in the middle of the night covered in sweat, she knew she was in for another bout of acute COVID symptoms. “It looked like I just stepped out of the shower,” she says. “That would lead to chills, and then the whole shebang would start all over again.”

In January, Elizabeth contracted COVID-19 again. After suffering a fever, shortness of breath, and a complete loss of smell, she got a coronavirus test, which came back positive. Astounded, she decided to channel her frustration by doing what she could, namely participate in research. “As a bioethicist I figured, let me try to look for some studies and see what’s available.”

She learned about the NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia study and reached out to volunteer. When Dr. Purpura heard her story, he offered to take her on as a patient in the new long COVID clinic, so she participates in both. Every few weeks, she contributes various samples and answers detailed survey questions. Thanks to Elizabeth and the other participants enrolled thus far, there is now even more long-hauler data that can be further analyzed and studied.

Combating stigma and shame

Though she’s part of a study and clinic with other long-haulers like herself, Elizabeth admits that she often feels alone in her situation. “I’ve had periods of intense anxiety and depression,” she notes, unsure of when this will all end.

The stigma and shame she feels about being a long-hauler is only now waning. Elizabeth describes difficult conversations she’s had with family and friends about why she still experiences symptoms and feels sick.

What we can offer at our clinic is validation for people — to let them know that they’re not alone and they shouldn’t feel stigmatized.

Dr. Lawrence Purpura

Many of Dr. Purpura’s patients have also expressed feeling shame from skeptical relatives, friends, even medical providers. “A lot of my patients have told me that people think they’re crazy when they say they’re still living with symptoms, whether it’s several weeks or several months after their infection,” he says. “What we can offer at our clinic is validation for people — to let them know that they’re not alone and they shouldn’t feel stigmatized.”

Elizabeth has found it reassuring. “More than anything,” she says, “it made me feel normal at a time when everything in my life had been abnormal for months at that point. Working with a specialized post-COVID clinic saves me and other patients weeks or even months of hassle and stress, because you don’t have to spend time convincing clinicians that you’re sick — they already believe you — and you can start identifying problems and potential solutions right away.”

Remaining hopeful

The bottom line is, no one knows how long post-COVID symptoms will last. But Dr. Purpura is hopeful.

“Based on what we have seen so far, the expectation is that not everyone is going to have these symptoms for a very long period of time and certainly not for the rest of their lives,” he says. “From the evidence we have from other viral infections, I think what we’re going to see is that some proportion of patients will have long-term symptoms that may range anywhere from one to three months; some patients will go on to have symptoms longer, up to six to nine months; and a much smaller percentage of patients will have symptoms longer than 12 months. That’s why these studies, like the one that we established here at NewYork-Presbyterian-Columbia, are so very important to answering that question.”

Dr. Sobieszczyk agrees. “Having a long COVID clinic that focuses on promoting a multidisciplinary approach is very important for the well-being and care of these patients,” she says. “It complements the ongoing and planned research efforts that will further our understanding of the underlying mechanisms.”

Today, Elizabeth still freelances as a journalist but is taking a break from teaching this semester. She still deals with prolonged post-viral symptoms — predominantly brain fog and daily fatigue, aches and pains, and the occasional headache. But she says she feels hopeful about being involved in the study and the long COVID clinic. “The sooner we legitimize long COVID and conduct studies on both the short-term and long-term effects, the sooner we’ll have protections and policies in place for people like us,” she says.

Dr. Purpura is optimistic that answers and better treatments are on the horizon. “Now that there is more attention on long COVID, there’s going to be more clinical research to answer the question of why this is happening, and eventually this will lead to better care and treatment for these patients,” he says. “The most important part are the patients who are driving this [study]. There are so many people volunteering to contribute. More research will lead to better treatment, and I see the clinic as a way to contribute to these efforts.”

Lawrence James Purpura, M.D., is a postdoctoral clinical fellow in clinical medicine in the Division of Infectious Diseases at Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons. He is an assistant attending physician and leads a long COVID clinic at NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving Medical Center, within the Division of Infectious Diseases. After attending Tulane University School of Medicine, Dr. Purpura was accepted into the Epidemiology Intelligence Service Fellowship with the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in Atlanta and was assigned to a branch that focuses on hemorrhagic fevers. The fellowship took him to West Africa, where he focused on the Ebola response and long-term complications in survivors. He has also completed a postdoctoral fellowship with ICAP, a global public health program at Columbia University.