Lillian Wald: A Pioneer in Public Health and Serving the Community

The trailblazing nurse began her career at NewYork-Presbyterian and went on to become a leader in social justice and public health care.

In 1893, 25-year-old Lillian Wald, a graduate of the New York Hospital Training School for Nurses, was asked to teach home nursing to immigrant families in New York’s Lower East Side. It was there that she witnessed firsthand the squalid conditions and lack of proper health care that the city’s poorest communities had to endure.

“That morning’s experience was a baptism of fire,” she wrote in her book The House on Henry Street. “To my inexperience it seemed certain that conditions such as these were allowed because people did not know, and for me there was a challenge to know and to tell.”

From that day forward, Wald made it her life’s mission to shine a light on health inequity. She went on to enact enormous change throughout her medical and humanitarian career, a pioneer of American public healthcare and a life-long champion of labor rights, civil rights, and women’s suffrage.

“Lillian Wald not only helped shaped public health care as we know it today,” says Joan Halpern, Vice President and Chief Nursing Officer at NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center, “but brought national attention to the powerful impact nurses have on the communities they serve. NewYork-Presbyterian is proud to be part of her legacy.”

An Upper-Class Childhood Left Behind

Wald was born in Cincinnati, Ohio, in 1867 to wealthy Jewish-German parents and as a child attended private school in Rochester, New York, after her family relocated. When she was 16, she applied to Vassar College but was rejected because the school deemed her too young. So, Wald decided to pursue nursing.

She attended the New York Hospital Training School for Nurses, which later became part of what is now NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center, and graduated in 1891.

Wald enrolled in the Women’s Medical College a year later, and after her eye-opening experience teaching in the Lower East Side, she and classmate Mary Brewster decided to leave school to teach and care for New York’s growing immigrant community full-time. “We were to live in the neighborhood as nurses, identify ourselves with it socially, and, in brief, contribute to it our citizenship,” Wald wrote.

“She had too much individuality to be willing to lose herself as a cog in an established institution. Instinctively, she wanted to change things — to do better,” wrote R. L. Duffus, Wald’s friend and the author of her 1938 biography.

The 1891 graduating class of New York Hospital Training School for Nurses (Wald seated on the far left).

Photo: Courtesy of the Medical Center Archives of NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medicine

A nurse from the Henry Street Settlement climbs a tenement roof.

Photo: Courtesy of the Medical Center Archives of NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medicine

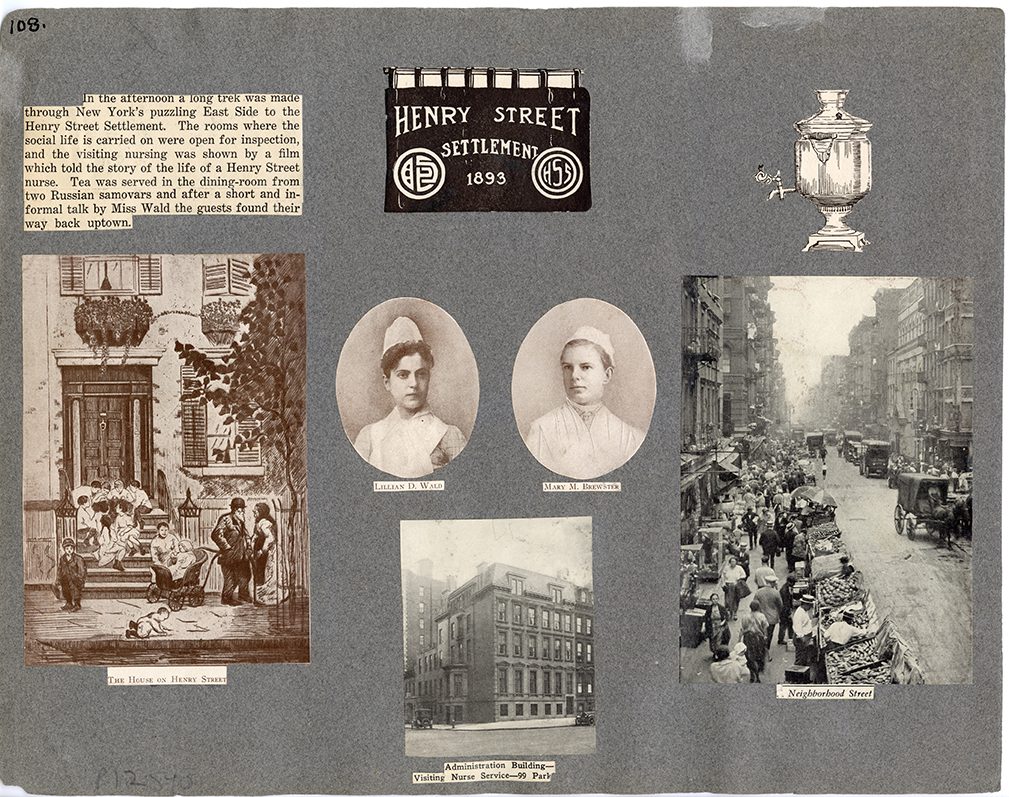

Lillian Wald and Mary Brewster depicted on a scrapbook page, assembled by the New York Hospital Training School for Nurses.

Photo: Courtesy of the Medical Center Archives of NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medicine

The Growth of the Henry Street Settlement

Ward’s initiative became known as the Henry Street Settlement, which still exists today as a not-for-profit social service agency. Through her work in the community, Wald created the first public health nursing program in the country, and she coined the term “public health nurse” to describe this type of aid that served people directly in the community.

Focusing primarily on the care of women and children, the Settlement gradually grew in both size and reach, guided by Wald’s mission to “unite people through their human and spiritual interests.”

Wald was a firm believer that everyone, regardless of gender, race, or socio-economic status, should have access to quality education, health care, and recreation. In its first three decades of operation, the Henry Street Settlement gained almost 100 nurses, opened one of New York City’s first playgrounds, launched boys’ and girls’ summer camps, and opened both a neighborhood theater and music school.

It also expanded its resources to include vocational training, home economics classes, and instruction in prenatal care. Wald wrote in her 1934 book Windows on Henry Street: “Never in all the years have we on Henry Street doubted the validity of our belief in the essential dignity of man and the obligations of each generation to do better for the oncoming generation.”

Community Care Leads to National Change

In 1900, Wald persuaded the Board of Education to hire a special education teacher to instruct students with physical and learning disabilities. Two years later, she pushed the New York City school system to hire Lina Rogers, a Henry Street nurse, who would become the first school nurse in the United States. Rogers’ success led the Board of Health to deploy school nurses across the country.

A staunch supporter of racial equality, Wald ensured that all classes at the Henry Street Settlement were racially integrated. She was a founding member of the NAACP, whose predecessor, the National Negro Committee, held its first conference in 1909 at the Henry Street Settlement House.

Wald was also dedicated to the abolition of child labor as a member of the National Child Labor Committee, a group whose efforts directly led to the creation of child labor laws and the Federal Children’s Bureau. While she and other female activists did not have the right to vote, Wald wrote that their ability to inspire political change was “a symbol of the most hopeful aspect of America.”

A Life-Long Legacy of Service

During a radio broadcast celebrating Wald’s 70th birthday in 1937, Sara Roosevelt, President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s mother, read out loud a letter her son had written to Wald, honoring her “unselfish labor to promote the happiness and well being of others.”

Wald died in 1940 after a long battle with illness, and a few months later a tribute was held at Carnagie Hall to honor her legacy. About 2,500 people attended, including the President, New York’s governor, and New York City’s mayor, who made speeches venerating Wald’s life-long commitment to serving others. Today, Henry Street Settlement remains a neighborhood fixture in the Lower East Side, giving New Yorkers access to health care, social services, and the arts across more than 50 programs.

“Wald dedicated her life to making quality health care attainable to all New Yorkers,” says Halpern. “We are proud that her training and nursing roots can be traced back to our institution, and her mission continues to guide NewYork-Presbyterian’s work to this day.”