It Happened Here: Anna Maxwell

The “American Florence Nightingale” revolutionized the nursing profession over her 30-year career at what is now NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia — and during times of war.

The flag flew in two wars, on two continents, and, in 1918, it flew in a parade honoring the woman who had imbued it with so much meaning.

In 1898, during the Spanish-American War, the flag hung over Anna Maxwell’s tent at Camp Thomas in Georgia, where she oversaw a team of nurses treating soldiers during a typhoid epidemic. And it was with her in France during World War I, as well, before making its way back to NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving Medical Center, where it resides today.

“It is a significant piece of history for women and for the nursing profession,” says Courtney Vose, vice president and chief nursing officer for NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving Medical Center, NewYork-Presbyterian Allen Hospital, and NewYork-Presbyterian Ambulatory Care Network.

Vose recalls how excited she was when Noah Ginsberg, now the director of laboratory services at NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia, found the historic flag in a storage area four years ago. It didn’t take long to recognize the flag’s storied past: a brass plate, nailed to the wooden frame around it, notes where it had flown.

“The flag appears in a picture of the Red Cross nurses marching in formation at a parade in France in 1918 that was given in Anna Maxwell’s honor,” Vose says.

A Hands-on Visionary

Anna Caroline Maxwell was a pioneer of the nursing profession who paved the way for nurses in the military. During her nearly 30-year career at what was then Presbyterian Hospital in New York City, she not only helped establish the U.S. Army Nurse Corps, but she also served as director of nursing services during World War I, which culminated in her receiving France’s Médaille de l’Hygiène Publique (Medal of Honor for Public Health).

“When I walk by this flag, it gives me chills because I think about how some of our nurses are serving in the military as paid and commissioned officers. It started here,” says Vose. “To think how much longer it would have been, or if it ever would have happened, if it hadn’t been for Anna. … She’s the one who had the idea. She was the visionary.”

Portrait of Anna Maxwell that hangs today at NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving Medical Center.

Anna Maxwell was born in Bristol, a town in western New York State, in 1851. When she was 23, she became an assistant matron at the New England Hospital for Women and Children in Boston. It was during this time that she received training in obstetrics, which inspired her lifelong interest in nursing. In 1878, Maxwell studied at the Boston City Hospital Training School for Nurses under Linda Richards, the first professionally trained nurse in America, who would become her mentor. Over the next several years, Maxwell established a nursing school in Montreal, and served as superintendent of the Massachusetts General Hospital Training School for Nurses.

In 1889 she returned to New York to head St. Luke’s Hospital Training School for Nurses, but she was soon recruited to oversee Presbyterian Hospital’s new nursing school. According to the hospital’s historical account, Dr. W. Gilman Thompson, president of the Medical Board, asked to set aside funds for the school so that “Presbyterian shall be the best hospital in every respect in this city and in this country.”

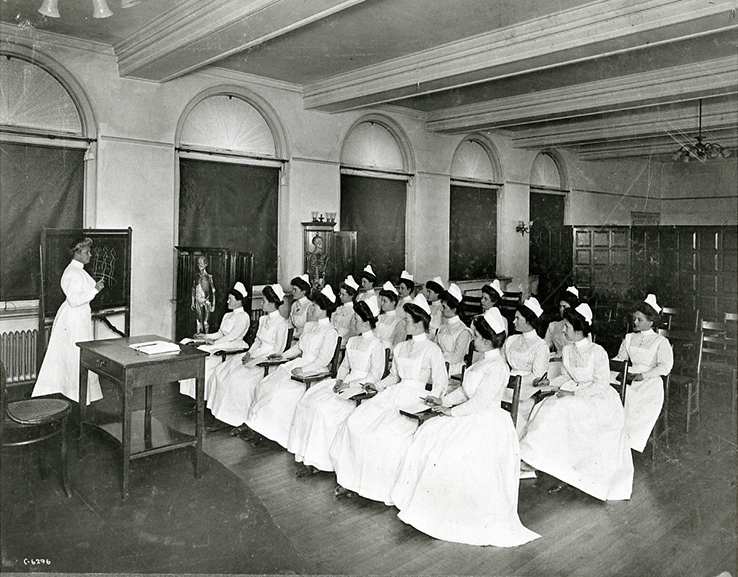

Maxwell was the first choice to serve as director. She immediately hired graduate nurses from other hospitals to oversee the hospital’s wards. She established a formal two-year curriculum, which would soon be increased to three years and included instruction and practice in medical, surgical, and obstetric nursing as well as oral and written exams. Maxwell herself gave lectures and demonstrations and even co-authored a textbook, Practical Nursing, in which she shared in the preface the inspiration for her career in nursing: “If [the book] succeeds in aiding those who are devoting themselves to the alleviation of human suffering, we shall believe that it has accomplished its mission.”

The Presbyterian Hospital Training School for Nurses — today’s Columbia University School of Nursing — opened on May 1, 1892. Student nurses worked and studied 12 hours a day, six days a week for a $9 monthly stipend. Two years later, 21 women were in the school’s first graduating class.

The American Florence Nightingale

In 1898, during the Spanish-American War, Maxwell traveled to Georgia to treat an outbreak of typhoid, along with soldiers suffering from measles, yellow fever, and malaria. She oversaw the nursing staff at the camp hospital, where 1,000 patients were admitted and only 67 died under her watch. It was there she earned the moniker “The American Florence Nightingale,” an homage to the English nurse who had famously tended to wounded soldiers during the Crimean War.

During World War I, Maxwell and others began lobbying on behalf of the nurses she had worked with at the camp.

“She politicked and fought for those nurses to become commissioned officers,” says Vose. “She really was the founder of military nursing.”

Maxwell and her fellow lobbyists petitioned the U.S. Congress to create a nursing corps to care for soldiers at war. In 1901, the Nurse Corps became a permanent division of the U.S. Army and, although she wasn’t considered for active duty during World War I, she visited mobile hospitals in France.

Stephen E. Novak, head of Archives & Special Collections at Columbia University’s Augustus C. Long Health Sciences Library, notes Maxwell went to the front on a hospital inspection tour in France.

“According to the diary of Anne Penland, the nurse anesthetist at Base Hospital No. 2,” he says, “Maxwell arrived at Étretat ‘unexpectedly’ on July 16 and departed on Aug. 6.”

It was during this trip that a parade was held in her honor. Novak cites Eleanor Lee’s History of the School of Nursing of the Presbyterian Hospital, New York: 1892-1942, which documents the occasion: “When [Maxwell] departed on her tour by motor a battalion of nurses marched down the streets of Étretat waving in their front ranks the large Red Cross flag that had served her during the Spanish-American War, and was now doing duty again in the same capacity.”

When you think about women who broke the glass ceiling … I would include Anna with them.

Courtney Vose

Anna’s Place

Maxwell retired in 1921 but stayed connected to the hospital until the end of her life. When she fell ill in 1928, she became the first patient admitted to the Harkness Pavilion. She died there on Jan. 2, 1929, and was given full military honors during her burial at Arlington National Cemetery.

“Anna Maxwell was second to none in her determination that entrants to the nursing profession be educated individuals who were prepared to become hospital and community leaders,” said Wilhelmina Manzano, Senior Vice President and Chief Nursing Executive & Chief Quality Officer at NewYork-Presbyterian. “She was dedicated to the advancement of nursing. Her values remain strong today as Columbia University School of Nursing prepares its students to be competent, confident and excel as clinicians, researchers, and nurse leaders in a rapidly evolving healthcare system.”

When the Columbia-Presbyterian Medical Center moved to its Washington Heights location just before she died, the first building to open was Anna C. Maxwell Hall, a residence for nursing students. Today, it is the site of the Milstein Hospital Building but, at the time, it was the first academic medical center in the world.

More recently, the Columbia University School of Nursing raised $250,000 to name Anna’s Place, a space in its new building where alumni and students can come together, relax, reminisce, and exchange ideas. A celebration of Anna’s Place is scheduled for May 2020 during Columbia Nursing’s reunion.

Today, nearly a century after her death, Vose still thinks of the impact Anna Maxwell continues to have on nursing — and NewYork-Presbyterian.

“When I think about how empowered and important nurses are in today’s world, I think back to the people who led the way,” she says. “Anna really was a pioneer in advancing the nursing practice, and having people understand the value it brings to healthcare and to our soldiers. … She’s tremendously important. When you think about women who broke the glass ceiling — we think about women today who are CEOs — and yet, for nursing, I think about who made nursing an important part of the healthcare system. I would include Anna with them.”