Tragedy & Healing: Inside the William Randolph Hearst Burn Center on 9/11

Twenty years after the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks, the burn center team reflects on how the unit came together to help survivors.

Twenty-one years ago, patients began flooding emergency rooms throughout New York City within minutes of the Sept. 11 attacks on the World Trade Center.

Then in the hours after the Twin Towers collapsed, hospitals were met with a disarming silence as medical teams began to realize there would be few survivors coming through their doors.

Many families still searching for missing loved ones looked to one place: the William Randolph Hearst Burn Center at NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center, the first comprehensive burn center in New York and one of the largest in the country.

“The burn center was crucial during 9/11,” says Dr. James J. Gallagher, director of the William Randolph Hearst Burn Center. “In truth, it was the epicenter of care because many of the injuries were burn- and fire-related.”

In the early hours of Sept. 12, a line of people clutching photos of missing family members formed at the entrance of NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center and stretched around the block— each person hoping that their loved one had survived and many wondering if they would find them on the eighth floor burn unit.

Over the next five months, the multidisciplinary team at the burn center cared for 18 severely injured patients and ultimately saved 11 of those individuals.

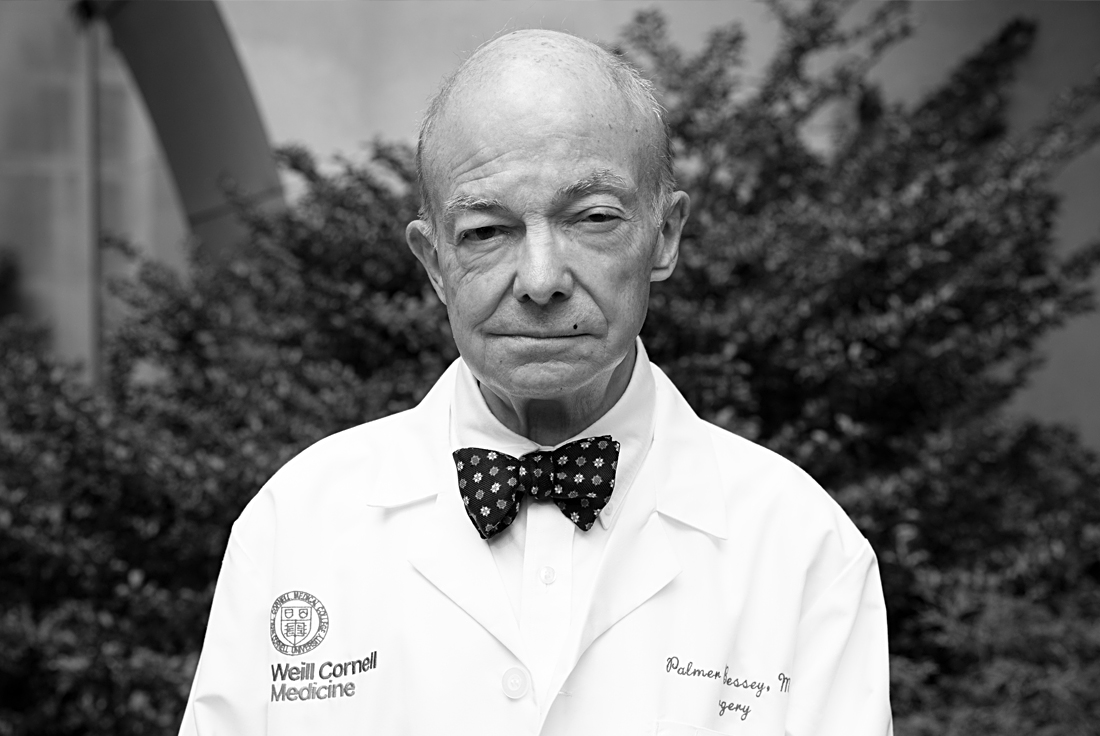

“It takes a long time to get over a burn,” says Dr. Palmer Bessey, associate director of the William Randolph Hearst Burn Center and one of the surgeons who cared for 9/11 victims. “It happens in a flash, changes your life, and always leaves a mark.”

The devastation of 9/11 also left an indelible impression on the burn unit team. Here, five members of the care team at the burn center recall the horror that unfolded on that tragic morning and the healing that came in the days, weeks, and months that followed.

“I Feel Gratitude”

Surgeon Dr. Palmer Bessey

On the morning of Sept. 11, Dr. Palmer “Joe” Bessey was in Baltimore administering board exams to future surgeons when a candidate came tearing out of a room, shouting, “The World Trade Center has collapsed!”

Thus began the biggest test of Dr. Bessey’s 21-year career at the William Randolph Hearst Burn Center. Dr. Bessey caught the first train back to New York so he could go to the hospital when he arrived that night but was told to get some rest and report to the operating room early the next morning. His first case was a rare procedure that’s performed on severely burned patients to relieve pressure in the abdomen caused by excess swelling. Before 9/11, “that surgery would happen less than once a year,” says Dr. Bessey. “I did four of those that day.”

Over the next two months, the burn team needed two operating rooms, five days a week to continually treat all of the 9/11 survivors, more than doubling their usual volume of surgeries at that time.

“They all had huge burns,” says Dr. Bessey, who is also the Aronson Family Foundation Professor in Burn Care at Weill Cornell Medicine. “There were one or two patients who had one operation, but most would have several operations, as many as 10.”

Outside the OR, the work to help patients heal physically and emotionally continued. Doctors and nurses, physical and occupational therapists, nutritionists, social workers, and psychiatrists were among those who worked together to help care for patients. “Staff becomes family and the patient becomes part of that family,” Dr. Bessey says.

In the aftermath of 9/11, as the shock gave way to sorrow, Dr. Bessey took solace in the unity he saw in the unit and beyond the hospital. “It wasn’t just our tragedy, it was everybody’s tragedy,” says Dr. Bessey. “To be able to do something positive in a moment of tragedy for our whole city and country … I feel gratitude for that.”

“I Was the First Person Who Spoke To Families”

Unit Clerk Cathy Birch

In the days that followed Sept. 11, countless people hoping to locate lost loved ones were met at the front desk of the William Randolph Hearst Burn Center by Cathy Birch.

“I was the first person who spoke to families,” says Birch, a unit clerk at the burn unit for the past 20 years. “For that first week, all day, all night, people were coming with pictures of family members. It was picture on top of picture.”

All Birch could do was tape the photographs to the walls around the burn center and write down a name and contact number, knowing she would never pick up the phone. “It was heart-wrenching,” she says. “None of those people ever came to the burn unit. They were all lost.”

For the families of 9/11 survivors clinging to life, the burn center team became a source of strength. “Our purpose at that time was to support them,” says Birch, who helped arrange daily dinners for survivors’ loved ones. “We did everything and anything we could to keep these people comfortable.” And while Birch coped in her own way by taking short walks outside because “you didn’t want the families to see you cry,” she says there were times “you had to break down with them, give them a hug, whatever it took.”

Soon, the nation rallied around the burn unit as well: Boxes of homemade cards and letters from across the country began arriving at the hospital. “We had an abundance of get-well wishes and prayers for families and the staff,” recalls Birch. “I decided to put them on the walls of the unit to give the families some encouragement. They covered the entire eighth floor.”

They remained on display until the very last 9/11 survivor was discharged. In remembrance of 9/11, some of the letters were framed and are still featured along the eighth floor corridors today. “When I walk past these letters and cards and think back to that time, it’s gut-wrenching,” says Birch. “I don’t how we did it, but we did it. We made it.”

“There’s a Feeling of Family”

Physical Therapist Malvina Sher

Her second day of orientation at NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center had just started, but Malvina Sher already knew something was wrong. “People started getting phone calls and some people were crying,” says Sher, now a senior physical therapist. Finally, “the instructor stopped and said, ‘There has been an emergency. You need to go to the area you’re supposed to report to.’”

Sher raced to the William Randolph Hearst Burn Center and was immediately directed to a room where she helped the team stabilize one of the first World Trade Center survivors.

”I cleaned the patient, applied bandages, changed linens, positioned the patient — I did everything I was told to do, whether it was related to physical therapy or not,” she says.

That work continued for hours as more survivors filled the floor. “I’ve never seen that many patients with this extent of injury,” says Sher.

Undeterred, the burn unit pulled together. “Everyone was in overdrive trying to save lives,” says Sher. “I feel lucky because I was able to help people and be part of the most amazing team.”

In the days that followed, Sher reverted to her work as a physical therapist, and over time, helped patients stand, walk, and climb stairs again for the first time. “The recovery and rehabilitation are extremely long processes,” she says. “And when you work with a patient face to face for that long, you develop a personal relationship.”

It is that close bond with the patients — and the staff — that Sher values most about the burn center. “That’s the only place I wanted to work,” says Sher. Today, 20 years on, she still feels the same way. “There’s a feeling of family. It’s the compassionate care we provide not only to patients, but to each other.”

“We Were There for Each Other”

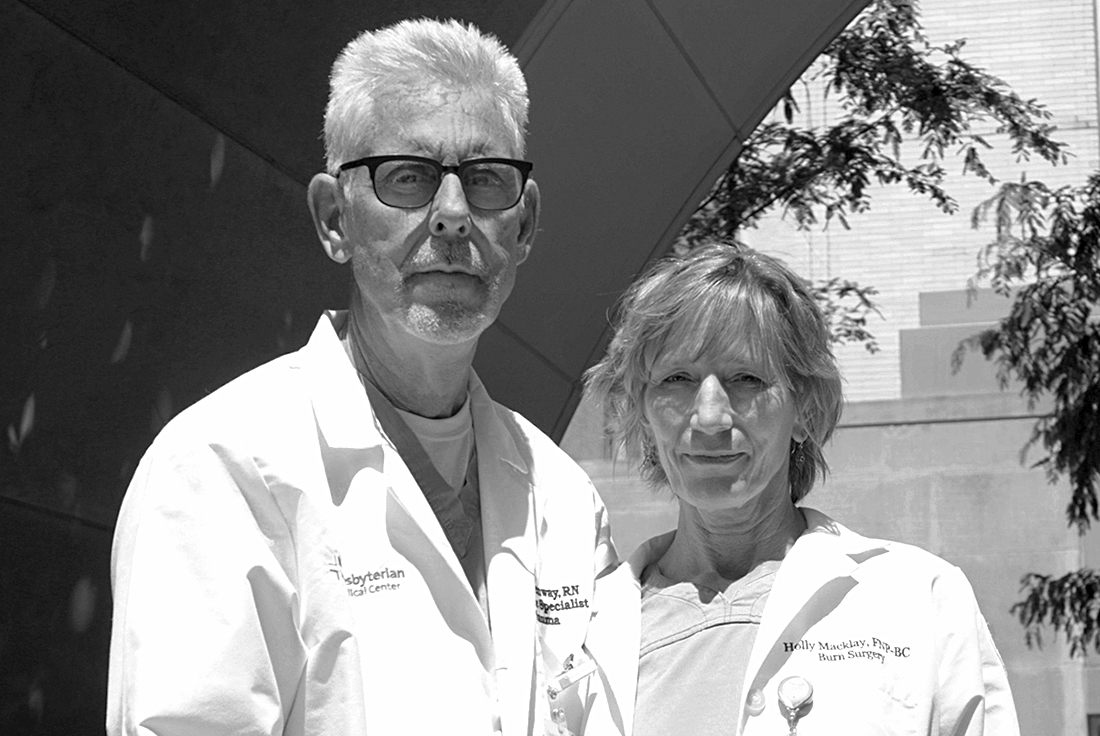

Nurses Andrew Greenway & Holly Macklay

Andrew Greenway and Holly Macklay met at the burn center when they both joined the team in 1984, and they exchanged vows five years later. Ever since, their marriage has given them strength during difficult times in their careers, especially when 9/11 struck and during the months that ensued.

Greenway was working his regular shift on the eighth floor when he heard that a plane had hit one of the Twin Towers. Staff immediately initiated the hospital-wide disaster plan to make room for 9/11 patients.

“The burn patients started coming in bursts. People were waiting for them — physicians, doctors, nurses, physical therapists, respiratory therapists, everybody was ready,” says Greenway. “Teams would get patients into the rooms, put IVs in them, make sure their airways were secure, and clean them very quickly.”

Because patients with severe burn injuries can experience extreme heat loss, “the team would descend on them, wrap them up and get them warm again and do the next one and the next one and the next one,” says Greenway, a clinical nurse specialist.

Meanwhile, Macklay was in the middle of getting her two young children off to school when she heard the news and watched on TV the first tower fall in real time. The couple alternated their hospital shifts so someone was always home with the children. So when Greenway finally walked through their front door at 1 a.m., within a few hours, “I jumped up and went in for my shift the next morning,” says Macklay.

In the unit, “there were a lot of patients who were profoundly and critically ill,” recalls Macklay, a nurse practitioner. “They were coming and going from the operating room and on life support.”

From the beginning, “nurses were involved in the whole recovery process,” says Macklay of the nursing staff. “We felt grateful that we were able to be a part of helping some of the survivors.”

“I think a nurse’s job is to hold people up,” adds Greenway, who also valued that he and Macklay could support each other during this time.

Over the next month, Macklay and Greenway continued to tag-team caring for patients at the hospital and for their kids at home (the oldest of which is now a NewYork-Presbyterian paramedic). They only shared fleeting moments in the evening before falling asleep when they welcomed the chance to reconnect and talk about what they were grateful for each day.

“We always have had the great fortune to be there for one another,” says Greenway. “It’s a career saver, a soul saver, and a life saver.”

The last 9/11 burn patient was discharged from the hospital on Feb. 22, 2002, 164 days after the terrorist attacks. Today, the William Randolph Hearst Burn Center performs roughly 30 surgeries every month and treats more than 5,000 patients, including more than 750 inpatients, each year.