A Veteran Paramedic Reflects on September 11

John Episcopo was one of NewYork-Presbyterian’s first responders on the scene at the World Trade Center. Here, he recounts that day for the first time.

I’ve been a paramedic at NewYork-Presbyterian for over 20 years. I joined the Fire Department in 1995 and began my EMS career in 1996.

I consider my co-workers my second family. We would do anything for each other — at work and outside of work. We can count on each other. The friendships I’ve made here are impossible to explain. We sacrifice ourselves to help total strangers. We sacrifice our emotional stability, our private time with our families, and our financial stability. And we do it because we have this drive to help other people.

On September 11, 2001, I was 24 years old. I wasn’t supposed to work that day. I exchanged tours with another co-worker because I was helping a friend move. So, my co-worker worked my Saturday and I worked Tuesday.

My partner, Eddie Santiago, and I came to dispatch, punched in, got our equipment, then met two of my other partners, Keith Fairben and Mario Santoro, for breakfast near NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center. Keith and I worked sister trucks, so we always tried to back each other up on different jobs. Mario was my partner on other days.

After we left breakfast, Keith and Mario came over the hospital radio frequency, saying that a plane had struck the World Trade Center and that they were en route to the assignment. Eddie and I were watching the news unfold on TV, monitoring all the radio frequencies, Fire Department, EMS, and police.

Watching on TV, I knew it was serious. I knew this was going to be a major incident. It seemed very surreal, like I was watching a movie. We were instructed to gather a bunch of supplies — we threw extra supplies into our units and waited for the word to go downtown.

First Among the First Responders

Going down to the towers, we knew we were going to be met with a lot of traumatic, horrific injuries. We knew it was going to be a long ordeal. The minute our director said, “OK, let’s go,” we went with a convoy of two supervisor vehicles, the trauma attending, our director, our manager, and four units.

We jumped on the FDR Drive southbound. At the time, it was a huge adrenaline rush, so I wouldn’t say I was scared. I was in a state of shock. All the units were on the hospital private frequency. But the radio was silent. That’s typical for a major incident — you only transmit important information.

The towers soon became visible. Both were on fire and smoking. I turned to Eddie and we made an agreement that whatever happened, whatever the assignment was, we would stay together. We kept that promise to each other.

We arrived and, while we were waiting for our orders, we just kind of looked around. We could see debris falling. There were loud noises, and we could see the smoke up high.

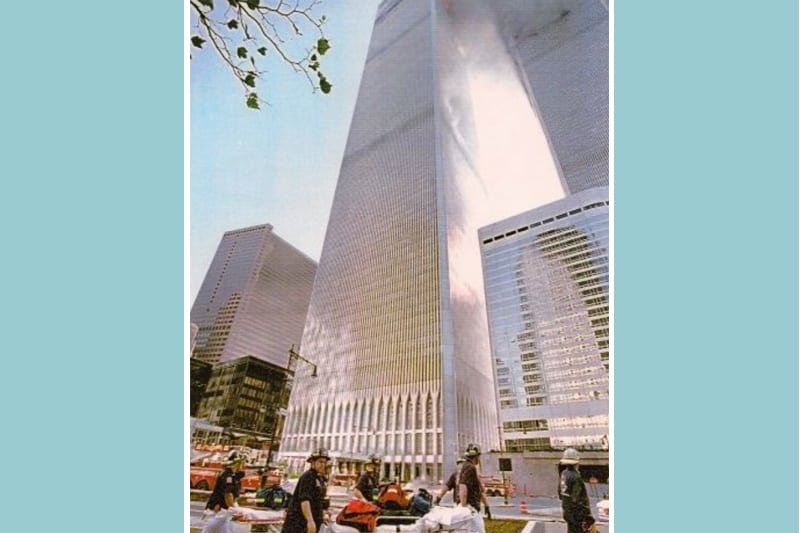

We were told to set up a forward triage area at Vesey Street. I remember seeing a photographer taking pictures of us with the towers burning in the background and thinking, “What is wrong with this guy? This is ridiculous. Why are you here?” And then he yelled, “Run for your life!” At that point we all stopped and looked up. The sky above us was completely gray. Without speaking, everyone gave each other approval to do what they needed to do to survive.

We’re always taught that your safety comes first, and then your partner’s safety, and then the patient’s. That exchange gave us the permission to just worry about ourselves. We scattered. I ran southbound on West Street. As the tower came down, I was thrown 20 yards or so, and I ended up landing underneath the South walkway, which connects the World Trade Center to the Financial District. The North walkway ended up collapsing, but the South walkway stayed intact. I landed against something on my right side, and I remember just curling into a ball and wanting to put my entire body underneath my helmet. I just stayed in the fetal position underneath my helmet.

The noise got louder and louder; it sounded like static. At one point I thought my eardrums were going to pop. And just when I thought I couldn’t take it anymore there was complete silence. I didn’t know if I was alive or dead. I remember thinking to myself that if I was going to die, make it fast. I pictured a large piece of debris just squashing me. I opened my eyes to complete darkness. I took a breath and inhaled a large amount of dust, so I made myself vomit. Then I put my T-shirt over my nose and mouth. I still couldn’t see anything.

I felt my way around and, in front of me, I felt what I thought was the top of a tire, and I felt a little further and felt the spring of a car. I followed that up, and felt the corner panel, and actually put my hand on the hood. I gathered up all my strength and reared up as hard as I could. I lunged over the hood and ended up falling on the other side of the car. Once I landed, I looked up and in the distance was a white light. Your life flashes before your eyes — I can attest to that. I saw my family, friends, everyone who’s very close to me.

But the white light was just the haze getting thinner. The wind was blowing in the other direction. So that was just clearing.

I got up and started stumbling over debris. I tripped over a firefighter, helped him up. He continued on his way, I continued, and then I tripped and fell on Eddie. He had a large piece of metal on his legs and couldn’t free himself. I lifted the metal, helped him up, and we continued southbound on West Street. The haze had lifted on that side, and I never looked back.

One of the emergency vehicles from the NewYork-Presbyterian convoy, all of which were destroyed.

Honoring a Partner’s Agreement

Eddie was having difficulty breathing, but we continued walking. There happened to be an NYPD truck that was running, unlocked, with the keys in it. So we jumped in. Three other people jumped in with us, and I drove toward the Brooklyn Bridge.

Once we got to the foot of the bridge, where the entrance to the FDR was, the truck died. We got out and started walking when a regional EMS supervisor, Terry Smith, pulled up. We identified ourselves as EMTs from NewYork-Presbyterian and asked for a lift. I jumped in the front; Eddie in back. There were people everywhere, evacuating Lower Manhattan. They were coming over the bridge, going uptown on the FDR.

Eddie passed out, so I turned around, opened his airway and stimulated him. He came to and then passed out again.

Terry stopped the vehicle and put oxygen on him. Eddie came around a little bit, and we heard people screaming, “Oh my God! Oh my God!” I looked out the back window and saw that the second tower was collapsing. We continued northbound and came back to NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell. Once we got past dispatch, I was hanging out the window waving, trying to get their attention because I knew I was going to need help with Eddie. We pulled up to the ER entrance, and there were wheelchairs and stretchers all over the place. Eddie had passed out again. I picked him up, threw him onto the stretcher, and they took him inside.

One of my managers asked where everyone else was that we went down with. I told him everybody scattered and he said there were a couple of people who hadn’t been heard from. I said, “OK, give me a truck, give me a partner, and I’ll head back down.” He told me that I had to go to the ER. Another manager took me aside and said, “Listen, you guys want to go down. No problem. Just come into the bathroom. You need to clean yourself off. And then once you clean yourself off, I’ll go down with you.”

“By us sharing the story, it’s fulfilling our promise that the people who died that day — our friends, our family, our co-workers — will not be forgotten.”— John Episcopo

I went into the ER bathroom and looked at myself in the mirror. I was covered in dust — completely white. I went to wash my face and my wrist was broken. That’s when the pain started. The adrenaline started coming down. A nurse in the ER overheard us and said, “John, come with me.” She grabbed me, and the next thing I knew I was in a hospital gown on a stretcher with doctors and nurses treating me.

I knew I was injured. I knew I needed help. I knew I had been through a traumatic incident. I let them take X-rays and draw blood. But I couldn’t sit and wait for the results — because of what was going on, knowing that my co-workers were missing.

I was in the ER till around noon. At that point I had enough, so I sneaked out and got a uniform and waited to hear from my co-workers. Some radioed that they were OK. Some were on the ferry to Staten Island.

I left the hospital that night around 8 and drove home. When I got there, my father was waiting for me with a couple of friends. I wasn’t really that hungry. I took a shower and just went to bed.

I was on workers’ comp for three and a half months because of my injuries. But I came back to the hospital to volunteer my time that Thursday, September 13. I couldn’t lift anything because of my broken wrist, but I could drive, I could do paperwork, I could answer phones. So that’s what I did for the amount of time until I was cleared. I volunteered my time.

I have conditions from that day — medical and emotional. I’m followed by the World Trade Center monitoring program. I do have nightmares more frequently around September. They’re less frequent now than within the first five years. Loud noises startle me; the effects of that day stay with me and will be with me for the rest of my life.

Moments before the South Tower collapsed, a photographer took this photo of a group of NewYork-Presbyterian paramedics and EMTs at the tower’s base. His warning to run saved their lives.

A convoy of NewYork-Presbyterian vehicles driving to the site. “My team had a convoy of seven vehicles heading down the FDR,” recalls Episcopo. “We parked in front of the Marriott on the West Side Highway and were gathering our equipment to set up a forward triage station at the corner of Vesey and West streets. The tower came down on us and we all ended up in different directions, helping people as we stumbled upon them. All our vehicles were destroyed. We all ended up in the ER as patients at some point in the day.”

All of the emergency vehicles in the NewYork-Presbyterian convoy were destroyed when the towers collapsed.

Steven Friend (third from left) with paramedic Lori Beninson (far left), paramedic Alex Massac (far right), and former NewYork-Presbyterian medics at the forward triage station.

A NewYork-Presbyterian paramedic, John Bergman, at the site with a firefighter.

Keeping Their Memories Alive

I have a 1-year-old son now. Every September 11, we start our day at the hospital, then we go to the ceremony at the chapel. Afterward, we come to the EMS department and we go to the memorial. Keith’s fire company drives in from Long Island and shares the morning with us. After that, my co-workers and I and Keith’s company drive to the cemetery and sit around his grave telling stories. Then we all go out to lunch, and later that evening we go to his firehouse, and we have another memorial service there.

We have done this since 2001. And we will continue to do it. Through the years, I feel people are forgetting. We have a generation now that’s growing up that wasn’t alive when September 11 happened.

Early on, telling the story for me was difficult, and it still is. But people need to hear it, especially people in the emergency services. People who weren’t alive when it happened need to hear the story so they can remember. And by us sharing the story, it’s fulfilling our promise that the people who died that day — our friends, our family, our co-workers — will not be forgotten. And that’s why I’m sharing the story now. This year is the first year that I started sharing the whole story.

The birth of my son made me want to do this. I want him to know what happened that day. I’m not going to share it with him anytime soon; I will later on when he can understand it a little bit. But I want to share the story to educate people and have them know that your life can change within a minute. And even though I survived, my life and my personality are completely different than how I was before 9/11.

At the 10-year anniversary, my wife and I went to the museum and we walked around the waterfalls. We found Keith’s and Mario’s names etched in the wall. It’s beautiful down there.

They are the true heroes because they lost their lives; they paid the ultimate sacrifice trying to help strangers. Yes, they were doing their job. Yes, they were getting paid. But they were deep in the thick of things. And the intention was to help as many people as they could. And if they were alive today, and another September 11 were to happen, we would all be in that same position, and we would all be deep into the incident knowing that that could be it.

I can’t explain to you the reasoning behind me being OK with sacrificing myself for others, because I don’t know. I just know that if I’m working, and something were to happen, then I would be there. And it’s painful to say, because I know what my family would be losing, and that’s unexplainable. I don’t understand.

But I hope that people can understand the willingness to self-sacrifice for strangers for the greater good. To my co-workers and friends in the business — your life can change in an instant. You need to cherish what you have, and appreciate everything and enjoy life, because you never know when you’re going to be in the wrong place at the wrong time. You have no control over that.

In the ensuing years, I ran the Special Operations Division with the EMS department of NewYork-Presbyterian. I teach the emergency vehicle operations course and the EMS safety course along with other courses. So, my experience on September 11 guided me toward the education part of the job, which I never thought that I would get into. I enjoy it very much.

I hope that I convey to the students the feeling of what it was like, and by describing it so vividly, I can tell them that it smelled like smoke, that the noise was like static but, unless you were there, you still wouldn’t get it. It’s more than just reading it in a book or watching it on documentaries, but surviving September 11 made me the person I am today.