Inside NYP: Dr. Ronald Lehman

A leading spine surgeon reflects on how his military service inspired his career and the crucial roles — both as a doctor and a veteran — he has played in helping heal the injured at home and abroad.

I grew up in a small coal and farming town of about 1,900 people in Pine Grove, Pennsylvania. It was very Friday Night Lights — we had more people in the football stadium on Friday nights than we had in the town.

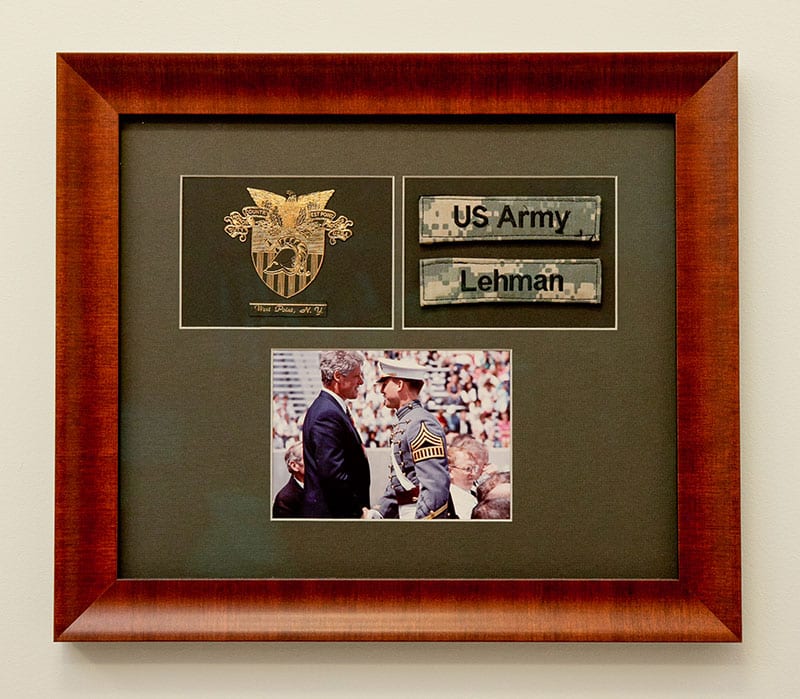

In high school, I joined the JROTC and worked my way up to becoming the Battalion Commander (the highest ranking cadet). JROTC instilled discipline through wearing uniforms, inspections, and constant attention to detail. I think that gave me a foundation for the path ahead. I then attended the United States Military Academy at West Point. I was considering becoming a dentist, but they didn’t allow cadets to attend dental school — they did, however, allow 2 percent of the graduating class to go to medical school, and I was fortunate to be selected. I thought, “I don’t know if I’m smart enough, but I’ll go down this pathway and see what it leads to.”

Since I played sports my entire life — and had ankle and wrist fractures — I was initially thinking about family practice with a sports medicine fellowship. Orthopaedics was familiar to me because when I was 7, I sustained a Type III supracondylar elbow fracture, which is a very bad fracture but also caused a laceration of my artery and nerve. I couldn’t straighten my arm for over three months; nor could I touch my thumb to my small finger because my ulnar nerve was damaged. I didn’t realize at the time how bad the injury truly was, and am lucky to have made a complete recovery.

Following West Point, I attended Jefferson Medical College in Philadelphia. During my third year of medical school, my brother-in-law sustained a spinal cord injury and was transferred to Jefferson for his spine care. That’s one of the things that got me thinking about the spine. I also realized that I had the ability to do harder, longer surgeries like scoliosis and spinal deformity because it requires you to maintain focus for 8-to-12-hour surgeries and I knew, because of my military training, I was programmed to do that sort of thing.

After medical school I spent two years at the Pentagon as a General Medical Officer in the health clinic, then went to Walter Reed Army Medical Center for my residency. I went to Washington University in St. Louis for a fellowship in spine surgery, then I came back to Walter Reed for nine years as Chief of Pediatric and Adult Spine Surgery. I had the privilege of taking care of our nation’s heroes and their family members. I also had a unique experience in serving as the Consultant to the Surgeon General of the Army for spine, Consultant to the White House, and took care of the Special Operations personnel.

On September 11, 2001, I was at Walter Reed during the attacks and helped treat the casualties that were coming up from the Pentagon. Then we took care of the majority of the casualties coming from the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. Many of the injuries that we saw were much more complex than what we see in civilian trauma. Many of these patients had amputations and spine fractures, spinal cord injuries and paralysis, and open wounds. Because there weren’t enough plastic surgeons to go around, we did most of our own skin grafts, which isn’t something orthopaedic surgeons learn on the outside. I also learned minimally invasive surgery there, too, because we had a lot of young people who didn’t need a big incision and had to get back into combat.

In 2010, I did a six-month tour in Mosul, Iraq, as an Army combat orthopaedic surgeon. We were located right by the airfield, so it was a prime area for attacks. When you see someone come in right off the battlefield and you don’t have the same surgical equipment you would normally have in hospitals in the United States, you have to learn to provide the same quality care with not as much. The screwdrivers, saws, plates, rods, and everything we used weren’t the same. We didn’t have MRI; we had CT scan, so you had to learn to read a CT scan as well as you could read an MRI. I also saw rare injuries there like lumbopelvic dissociation, which is basically where the pelvis and the spine get dissociated from these big blast injuries. We later published a classification system for lumbopelvic dissociations and low lumbar burst fractures. Those things were completely unique to my experience, which other people just don’t get the opportunity to do.

Then, in 2014, I was recruited to return to Washington University and work again with Dr. Lawrence Lenke, whom I had studied under during my fellowship. Shortly thereafter, Dr. Lenke and Dr. K. Daniel Riew, who was also working at Washington University, and I were given a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to come to NewYork-Presbyterian to help establish a premier spine hospital, what is now the NewYork-Presbyterian Och Spine Hospital. I currently serve as Director of Degenerative, Minimally Invasive and Robotic Spine Surgery. Here, I do big scoliosis and kyphosis cases. I treat kids and adults. I do minimally invasive surgical discectomies and oblique lumbar interbody fusion procedures and use microscopic and robotic assistance whenever it provides the best approach for the patient. Each of the things I learned while training in a military setting helped me perfect all these different types of surgeries. It’s like being this utility infielder for the Yankees as opposed to the star first baseman. I perform every surgery in spine and utilize my experience and training doing complex surgeries by transferring those principles to include robotic and microscopic surgical techniques as well.

After 17 years as a Lieutenant Colonel in the United States Army, the lessons I learned were how to take the best care of patients. I think ultimately when you listen to the patient, they tell you what they need and what their goals are. I choose each operation for what the patient needs and what’s going to benefit them the most. If the patient does well, everyone does well, and they and their families can return to their previous activities. I think all of those things are really learned from taking care of the casualties and caring for their family members. In a socialized setting, which the military is, you work as hard as everyone else, you get paid the same, but you’re doing that to take care of people because that’s the most important thing that we do.

Dr. Ronald Lehman is the Director of Degenerative, Minimally Invasive and Robotic Spine Surgery at NewYork-Presbyterian Och Spine Hospital and a tenured Professor of Orthopaedic Surgery at Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons. He is a nationally recognized expert in the treatment of adult and pediatric spine conditions.