In “Left on Tenth,” Writer Delia Ephron Brings Her Cancer Journey to the Stage

While navigating grief and falling in love, the novelist and screenwriter discovered she had leukemia – and turned to her doctor at NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center to help her beat it.

Photo credit: Elena Seibert

While watching rehearsals for her new Broadway play, “Left on Tenth,” writer Delia Ephron admits she was often brought to tears. It was adapted from her bestselling memoir and captures a time in her life when she navigated grief, found love, and faced down a life-threatening form of leukemia, all within the span of a few years.

“There are some days where I’m completely overwhelmed, and I start to cry,” says Delia. “It’s extremely powerful and difficult and joyful for me to watch this play come to life.”

The play starts in 2016 with Delia mourning her husband of 38 years, Jerry, who died not long after her sister, writer Nora Ephron, both from cancer. Delia is on hold with a phone company, trying to restore her internet after disconnecting her husband’s landline. She channels her frustration into her writing and publishes an op-ed on her experience in The New York Times.

In life and in the play, the article prompts a charming email from Peter Rutter, a Bay Area psychiatrist, who had also recently lost his spouse. The two apparently had been set up by Nora when they were 18, which Delia didn’t recall. After exchanging emails and talking on the phone for hours, Delia — one of the writers of the romantic comedy classic “You’ve Got Mail” — felt as if she’d been cast into her own rom-com at 72 years old.

“We just started writing these wonderful emails to each other, and we fell in love,” she says. “It was very magical.”

From ‘Boring’ Bloodwork to an AML Diagnosis

At the time, Delia was having regular checkups with Dr. Gail Roboz, a hematologist oncologist at NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center, who had also cared for her sister.

Years earlier, while evaluating Delia as a potential bone marrow donor for Nora, Dr. Roboz discovered she had abnormal cells that showed possible early evidence of a blood cancer that could develop into leukemia. This prevented Delia from donating her marrow and required her own health to be monitored closely.

Actress Juliana Margulies (left) as Delia Ephron in a scene from “Left on Tenth,” alongside Kate MacCluggage, who plays her oncologist, Dr. Gail Roboz.

For eight years, her bloodwork came back normal — or, as Dr. Roboz would describe it, “The most boring blood I’ve seen today.” Delia would incorporate that dialogue into her play to describe Dr. Roboz’s “a doctor with a touch of girlfriend” demeanor, as she describes in her script notes. “She has a way of connecting to patients that’s remarkable, but you also just sense the laser brilliance that she has,” says Delia. “The lines that she says in my book and on the stage, those are her words.”

Then one day in March 2017, soon after reconnecting with Peter, one of Delia’s routine checkups revealed something different: She had an aggressive form of leukemia known as acute myeloid leukemia, or AML, that starts in the bone marrow and develops in cells that are supposed to turn into white blood cells. “I was really stunned,” recalls Delia. “I had just fallen in love; I’d just played tennis [that morning]. I was so happy. I walked in and there it was, a cancer diagnosis. It changes your whole life.”

Dr. Roboz was also stunned. “This is an aspect of my job that is very awful, all the time,” she says. “And it’s extra awful when you have a long relationship with a patient and have to give this terrible news. In addition to that, I was giving terrible news to someone who was so happy.”

She quickly shifted her focus to putting Delia’s treatment plan in motion. Dr. Roboz recommended CPX-351, a new chemotherapy that was in clinical trials at that time. If the drug worked, it would clean out her bone marrow and kill the blood cells, especially the cancerous ones, with the hope that only healthy cells grow in their place.

Because of how vulnerable her immune system would be through the treatment, Delia was required to stay in the hospital for several weeks, but she never once doubted her care under Dr. Roboz, who is also the director of the Clinical and Translational Leukemia Program at Weill Cornell Medicine. “I thought, ‘I’m safe here,’” Delia says. “And I think that’s key with a doctor: feeling safe, feeling heard, knowing they’re accessible — and she has all that.” As Peter described it, which was mirrored in the play, Delia was fully “on the Roboz train” as she prepared to embark on the physical and emotional roller coaster of her cancer treatment.

Starting Treatment in ‘a Room Full of Joy’

Peter flew in the day after Delia learned of her diagnosis. She recalls: “I was three months into this deep passionate love affair. And he just said, ‘I’ll be there tomorrow.’”

The Saturday after he arrived, he proposed over French toast. By Monday, they went to the office of the city clerk to get their marriage license. On Tuesday, Delia checked into the hospital.

The couple turned to Dr. Roboz for something out of her job description — wedding planning. Could she help them arrange a wedding at the hospital? “Dr. Roboz said, ‘Oh yes, I could do that.’ It was like there was nothing she couldn’t do for us,” Delia says.

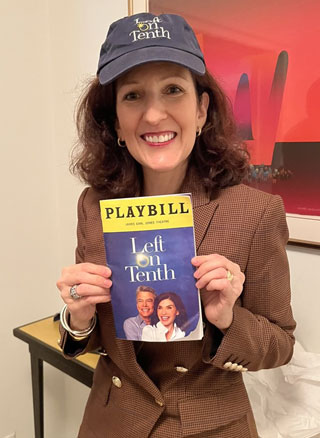

Dr. Gail Roboz shows her support for Delia’s new play “Left on Tenth.” Delia describes Dr. Roboz as “a doctor with a touch of girlfriend” demeanor.

Dr. Roboz and her team worked with patient services to book a space in a private dining room in the hospital. “We did everything we possibly could to make the wedding great,” says Dr. Roboz. The team even thought through questions like how to hide her PICC line and bandages, and making sure her medications were administered on time so that she would feel her best during the wedding.

With a few close friends by their side, the couple celebrated their wedding on a sunny day, early in Delia’s hospital stay. Hospital chaplain Dr. Cheryl Fox read the vows with them and signed the papers. They served Delia’s favorite cake, layer cakes from Amy’s Bread (chocolate with white frosting and yellow with pink frosting) and the chef at the hospital made Delia’s favorite pie, lemon meringue.

“I didn’t even know if I was going to survive, but there was so much hope in that room. It was a room full of joy,” says Delia.

As the weeks went on, the newlyweds would walk the hospital corridors to help Delia keep up her strength. Their devotion to one another drew admiration from staff and visitors, which Delia turned into a scene in her play.

“I was a little weak and Peter would be holding my arm, and people just kept stopping us and saying, ‘How long have you been married?’” Delia laughs. “I think they thought, given our age, that we’d been married for a hundred years and were some fantasy of romantic love that could last forever.”

“They were a super, super cute couple,” Dr. Roboz recalls. “They were walking around the hospital with an IV pole instead of walking around Central Park, but they still radiated.”

Surviving the Worst, Before Getting Better

After five weeks of chemotherapy, the treatment was proving successful, and Delia was released from the hospital. “Your marrow is gorgeous,” Dr. Roboz told her in a follow-up appointment.

The couple got to enjoy New York City together and travel. In August 2017, they visited Oregon to watch the total eclipse. But cancer was always in the back of her thoughts. “You’re in remission, but it’s on your mind all the time,” says Delia. “It’s not like you just go home and frolic.”

Another steep turn was coming. In November, a bone marrow biopsy indicated the cancer had returned. Because of how quickly and fiercely it came back, Dr. Roboz did not think chemotherapy would be enough this time. She encouraged Delia to get a bone marrow transplant, explaining that advancements in the treatment had made it safer for some older patients than before. It was the only thing that could “cure” her AML.

“For a long period of time, there was a cut-off for patients older than 60; they weren’t even sent for consultation,” Dr. Roboz says. “But through the years, the procedure got safer, and the supportive medications got better, so that number started moving up to a point where we can transplant patients in their 70s. Delia’s journey is incredible proof of how far the field has come.”

Dr. Roboz referred Delia to the stem cell transplant program at NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center, which was then led by Dr. Koen van Besien. He recommended a haplo-cord transplant, which involves transplants from two donors: an adult donor, and from an umbilical cord donated by a mother after giving birth. As Delia considered her odds and the ordeal ahead, Dr. Roboz told her, “Don’t be scared of the treatment, be scared of leukemia.”

“That was a stunning thing to contemplate,” says Delia.

She decided to go through with it. After some tests and another round of CPX to clean out her marrow, she underwent the bone marrow transplant in February 2018, with Peter by her side.

Early signs showed that the transplant took, as Delia’s bloodwork revealed a steady rise in white blood cells, red blood cells and platelets, indicating the new stem cells were producing healthy blood cells. But Delia’s road to recovery was harrowing as she battled complications. She grew severely ill, couldn’t eat, and her lungs filled with fluid. “I really just wanted to die,” she says. “I felt absolutely desolate.”

Delia Ephron and her husband, Peter, take a bow with the cast at the opening night curtain call of “Left on Tenth.”

Delia begged her loved ones to let her go, but Dr. Roboz was not ready to give up. “Give me 48 hours, and if I get somewhere, give me another 48,” Dr. Roboz told her.

“There was part of me that didn’t really want to die,” says Delia. “And when she said, ‘Give me 48 hours,’ I thought, ‘Oh, maybe I can make it.’”

“I really, really wanted her to hang in there a little bit longer. I really thought she was going to pull through to the other side,” Dr. Roboz says. She saw signs of Delia’s bone marrow recovering, despite how gravely ill she was. She points out that the bone marrow is a major organ, “and usually when the bone marrow is getting better and starts working again, a lot of the other problems that are making people horribly ill do start turning in the right direction.”

In that 48 hours, Dr. Roboz and her team were able to reduce the amount of fluid in her body and increase her nutrition and antibiotics, among other medical maneuvers. “What we needed was for those wheels to start turning in the marrow, producing some normal blood cells and letting the rest of the body fall into line once this major organ was up and running again.”

Delia began to improve. “Literally, it was 48 hours,” she says. “I suddenly woke up and Peter, my husband, he looked so handsome, and I actually had an appetite, and it was a flip.”

Delia says Dr. Roboz’s words stand out to her amid that terrible time. “I asked her about it, because it’s such a remarkable line, ‘Give me 48 hours…’,” recalls Delia. “And she told me, ‘Oh, small bites.’ I was fascinated that the answer was so brilliant and so simple. Because of course, for me, she was a hero. She’s a heroic person.”

Delia continued to heal, and soon, she went home to continue her recovery there.

A New Chapter Filled with Hope

Delia has now been cancer-free for more than six years. Today, she says she was saved by “love, medicine, friendship, and dogs,” adding that her beloved dogs, Honey and Charlotte, are characters in her play.

Whenever the curtains come down at the end of a performance, Delia’s wish is that the audience leaves with hope and some of the lessons she’s learned. “I hope they take a huge emotional journey. I hope they laugh; I hope they cry,” she says. “I hope they get more hopeful about their own lives and about taking chances and taking risks and understanding that you have to get past the fear.

“And also, just the joy – when it’s there, go for it.”