How This Artist and Mom Beat Metastatic Breast Cancer: Kiley Durham’s Story

When triple-negative breast cancer spread to her brain and then her spinal fluid, Kiley believed she only had months to live. Her NewYork-Presbyterian care team refused to give up, tailoring a treatment plan that helped her beat the odds.

One look at Kiley Durham’s paintings, and a theme emerges: women living life to the fullest, donned in colorful outfits that are as vibrant as the artist who created them. The joy in her artwork, however, belies the uphill battle she has fought for many years against metastatic breast cancer, which has threatened to take away the life she worked so hard to build.

Kiley likes to joke that her story sounds like the plot of a Lifetime movie: Plucky young heroine leaves her small Georgia hometown to pursue her fashion dreams in New York City. She goes from intern to head dress designer and creative consultant, meets the love of her life, and has two beautiful children — only to receive a diagnosis of breast cancer in 2017 that would later spread to her brain and cerebrospinal fluid, a condition that is considered terminal.

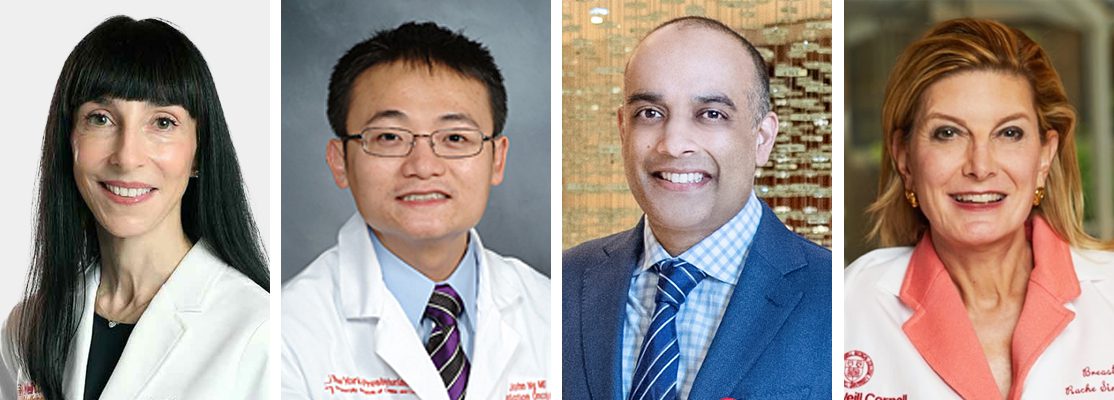

Her team of specialists from NewYork-Presbyterian and Weill Cornell Medicine, whom she calls her “dream team,” refused to give up, tailoring treatments to help ensure she would get to see her kids grow up — all while sharing in her tears, setbacks, and triumphs along the way.

“I went from believing I had three months to live and would never see my 39th birthday, to celebrating my 43rd birthday this past December,” she says. “My care team never made me feel like a number. They’ve all saved my life multiple times over.”

A Life-changing Diagnosis

At first, Kiley thought the lump in her right breast was related to breastfeeding, having recently given birth to her daughter, Maddy. At her eight-week postpartum checkup she asked her OB-GYN about it, who suggested she get imaging done, just to be safe. She went in for an ultrasound at NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center, and her scans concerned the radiologists enough that they ordered a same-day biopsy.

A few days later, she and her husband, David, received the news: She had early-stage triple-negative breast cancer, one of the most aggressive forms of the disease. “All weekend I had been waiting for the phone call, wishing it would hurry up and come. But in that moment, I thought, ‘I wish there was time for one more walk to the park, one more family dinner, one more snuggle with my son while watching cartoons,’” Kiley says. “That was the day my life changed forever.”

The first member of her care team that she and David met with was Dr. Rache Simmons, a breast surgeon at NewYork-Presbyterian, who helped Kiley understand her diagnosis and answered all the questions that lay heavily on their minds. Soon after she met Dr. Tessa Cigler, a medical oncologist, who would oversee her care.

At her first meeting with Dr. Cigler, Kiley expected the conversation to dive right into talk of chemotherapy or radiation; instead, they started with the hair loss she would experience during treatment. “I still had my very long, big post-pregnancy hair, and before we talked about anything else, she said, ‘We have to figure out what we’re doing about your hair,’” Kiley says. “We sat and talked about all the options, and that was when I knew I loved her. It was the most loving, human moment to take the cancer out of the room for a minute. She knew it was one little thing to help me get through this.”

Kiley and her family early in her treatment journey. Pictured, left to right: son DJ, husband David, Kiley, and daughter Maddy

Starting the Treatment Journey

Kiley began treatment in August 2017, starting with five months of intensive chemotherapy to shrink the tumor prior to surgery and help reduce the risk of the cancer spreading. During this time, Kiley underwent genetic testing, which revealed she had the BRCA1 mutation, a gene mutation that greatly increases the risks of breast and ovarian cancers. More than 60% of women with a BRCA mutation will develop breast cancer in their lifetime.

“This explains why she had breast cancer in her 30s,” says Dr. Cigler. “Women with the BRCA mutation also have a higher risk of developing breast cancer in the same or other breast in the future, as well as of developing ovarian cancer.”

Her genetic profile meant that it was better to take a preventive approach, which made a bilateral mastectomy, or surgery to remove both breasts, a better option for Kiley than just removing the lump. In February 2018, after completing her chemotherapy, Dr. Simmons performed the surgery. And because initial tests showed the cancer had spread to some lymph nodes, the surgery was followed by radiation therapy, overseen by Dr. John Ng, a radiation oncologist at NewYork-Presbyterian.

At times, Kiley’s treatment regimen was physically and mentally taxing as she tried to maintain a semblance of normalcy for her family. “The first day I wore my wig was to my son DJ’s first day of kindergarten, because he didn’t like people knowing that I was so sick,” she says. “There’s no good way to tell a 5-year-old that things are about to change drastically. It was surreal to keep going for them and try and pretend like everything was OK.”

To help her cope, her mom bought her art supplies to encourage her to start drawing and painting again, a passion Kiley had set aside when life got too busy with kids. “When I’m painting, everything goes away. It’s when I do my best thinking, and if I’m having a bad day, I can get lost in it,” she says.

The hard times felt worth it when her tests revealed no traces of cancer. “The chemotherapy took what was around a 5-centimeter mass and melted the cancer away,” Dr. Cigler says. “So at the time of her surgery, she had no signs of residual disease.”

During the last part of her treatment plan, five weeks of daily radiation therapy, Kiley believed she was in the clear. But as her sessions progressed, she was plagued with headaches and fatigue. She chalked it up to being busy preparing for a move — until the afternoon she blacked out. The next thing she knew, she was headed to the emergency room at NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center.

Kiley’s care team at NewYork-Presbyterian included, from left to right: Dr. Tessa Cigler, Dr. John Ng, Dr. Rohan Ramakrishna, and Dr. Rache Simmons.

Fighting a Devastating Prognosis

The ER doctors delivered the news: An MRI revealed that the breast cancer had spread to Kiley’s brain, creating a walnut-sized tumor that was pressing against her left eye and causing migraine-like symptoms. She would need surgery immediately.

Dr. Rohan Ramakrishna, a neurosurgeon at NewYork-Presbyterian, performed the surgery to remove the tumor. Afterward, she underwent radiation therapy to eliminate any remaining cancer cells. “As with the radiation following her mastectomy, we wanted to treat any potential microscopic disease that could be remaining in the surgical bed,” says Dr. Ng. A few months later, imaging revealed she had a lesion in the right frontal part of her brain, which was treated with a single, targeted dose of radiation. Kiley also began taking a PARP inhibitor, medication that targets BRCA-related cancer cells to reduce the risk of the breast cancer spreading further.

Dr. Cigler notes that triple-negative breast cancer often carries a high risk of metastasis to the brain and other sites. But Kiley’s subsequent brain scans consistently came back clean, and her energy was starting to return. In August 2019, to help celebrate her recovery, she and David went to Italy, one of their favorite countries to visit together.

At the end of the trip, Kiley began to suffer from headaches, backaches, and numbness in her legs and feet, so she returned to NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center for tests and imaging. Over Labor Day weekend, while at the beach with family and friends, she received a call from a care team member urging her to return immediately. They had devastating news: Her cancer was back, and this time it had migrated to her cerebrospinal fluid and meninges, the protective membranes that cover the brain and spine. She had a rare complication of cancer known as leptomeningeal disease (LMD), which impacts 5% to 8% of breast cancer patients and has a typical prognosis of two to four months.

“It was the first time my husband and I both really cried. We had to have some scary conversations that you’re not supposed to have in your 30s about your kids, about what you wish you had said or never said to each other,” Kiley says.

Her doctors, who meet weekly with other oncology specialists to discuss their most difficult cases, explored Kiley’s case with their colleagues. “There is no standard in treatment for leptomeningeal disease,” Dr. Cigler says. “It was a real team effort to come up with a plan that we thought would maximize efficacy, while being mindful of toxicities to preserve Kiley’s quality of life and her priority, which was to participate in family life.”

At the time there was emerging evidence that an immunotherapy drug, pembrolizumab, could be effective for triple-negative breast cancer, but it had not yet been approved for that purpose. Kiley’s team decided it was worth pursuing. “It was not standard, but we had a clear scientific rationale,” Dr. Cigler says. “We would do everything to get her access to this drug.”

Her treatment plan ultimately included pembrolizumab, an oral chemotherapy drug called capecitabine, and about three weeks of radiation. Even her radiation treatment wasn’t textbook. Instead of irradiating her whole brain and spinal cord, as was typical for LMD, Dr. Ng targeted radiation to areas where she felt pain or numbness and spaced out her treatment sessions to lessen side effects like brain fog and hair loss. “With the typical treatment, a patient’s quality of life is never quite the same again,” Dr. Ng says. “This was an example of when, as a doctor, you treat with your heart as much as your head.”

On her birthday in December 2019, three months after her immunotherapy regimen began, Kiley went in for her routine scans. Dr. Cigler’s news was the best gift she could receive: There were no signs of disease. “Leptomeningeal disease is a devastating diagnosis,” says Dr. Cigler. “So, Kiley is amazing — the fact that her body has stayed clear of leptomeningeal disease and that her brain has been stable now for so many years is an unusual and inspiring outcome.”

Overcoming One Final Hurdle

Kiley continued her immunotherapy and chemotherapy treatment for about a year, with regular imaging to ensure the disease wasn’t coming back. Then in January 2021, while she and her family were in the middle of a move to Connecticut, she felt a small pebble on her left breast along her mastectomy scar. Much to her shock, a biopsy revealed that Kiley had a different form of breast cancer called HER2-positive, which was completely independent of her initial diagnosis.

It seemed like her life was on repeat, where she’d go from beating the odds to facing another setback, but her care team rallied around her once again. She took an antibody therapy to shrink the tumor, had another surgery to remove the lump, and three weeks of radiation, followed by two years of a chemotherapy and antibody therapy regimen. In 2023, with her scans consistently showing no signs of disease and the chemotherapy side effects wearing on her, she and Dr. Cigler discussed going off treatment. “I was feeling completely worn down, and for the first time, I cried in her office,” Kiley recalls. “I remember she said, ‘We’ve kept you alive, and now it’s time for you to live.’”

Today, Kiley is a full-time artist in Connecticut who uses her art to help promote breast cancer awareness. She’s also enjoying the milestones she missed out on while battling cancer, like spring break trips with her family, birthday parties, and first days of school. She credits the unwavering support of her family and her care team — from the physicians to the nurses to the radiation technicians, who shared tears with her every time she came back for a new round of treatment — for getting her through the past six years.

“When other people ask me how I’ve managed, I tell them I just had really good people around me,” Kiley says. “They made me feel cared for as a person, not just as a patient. The reason I felt so confident that I could keep pushing forward is because I knew they weren’t going to let me go anywhere on their watch.”