How to Avoid Caregiver Burnout

To properly look after a loved one in need, caregivers need to maintain their own health and well-being.

One of the most important jobs in healthcare isn’t performed at a hospital or medical clinic.

It’s often in the home.

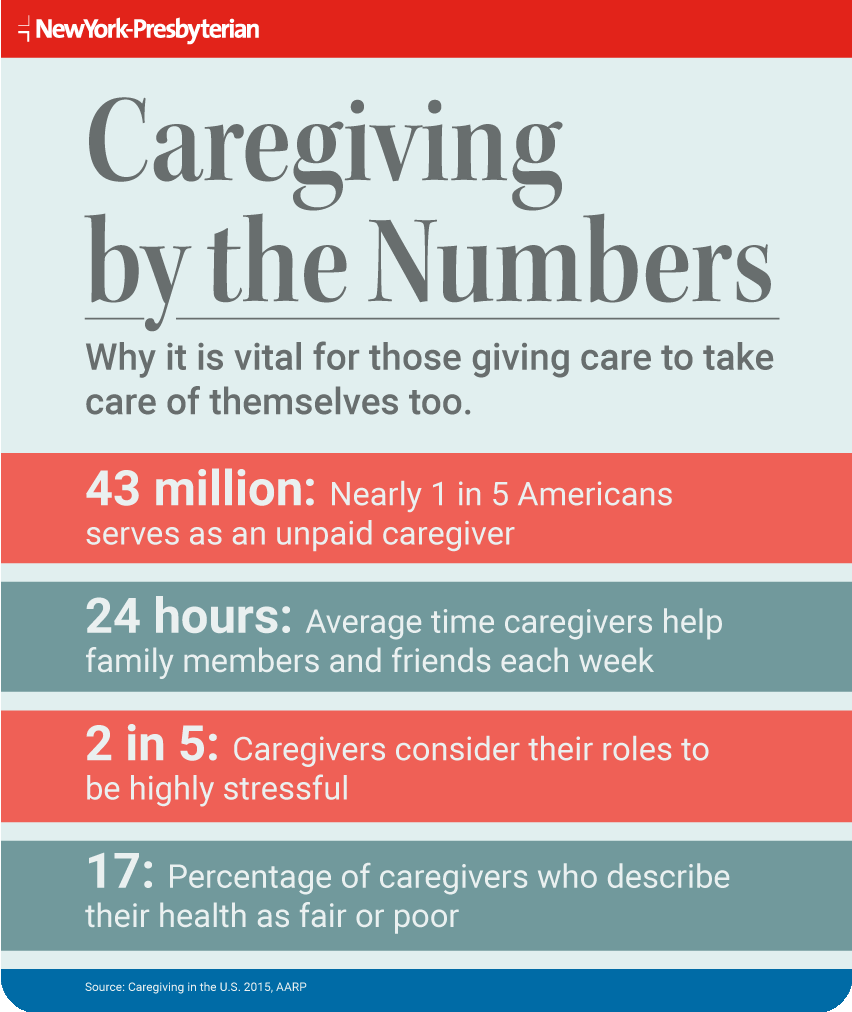

More than 43 million Americans — nearly 1 in 5 adults — serve as unpaid caregivers, a role that can be rewarding yet also demanding and isolating. For an average of 24 hours per week, caregivers help family members and friends with tasks both practical and personal, from transportation to and from doctor appointments to helping with dressing and bathing.

In spending so much time looking after someone else, though, they may neglect caring for themselves.

Two in five caregivers consider their role to be highly stressful, and one in five feels that providing care has worsened their health, according to “Caregiving in the U.S. 2015,” a research report from the AARP Public Policy Institute and the National Alliance for Caregiving. The study also found that 17 percent of caregivers describe their health as fair or poor, with the percentage rising for higher-hour and longtime caregivers. By comparison, 10 percent of American adults say they’re in fair or poor health.

Being a caregiver is uniquely challenging, says Sandy Regenbogen-Weiss, a licensed clinical social worker and the manager of the HealthOutreach program for older adults at NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center. On top of managing new responsibilities that drain time and disrupt routines, caregivers must cope with a wide range of emotions, including grief over having a sick loved one.

“It’s exhaustion, it’s fear, it’s anger. There’s definitely guilt,” says Regenbogen-Weiss. “There are just so many emotions, and there’s no way of knowing how long it’s going to go on.”

Caregivers often insist that they put their loved one’s needs first. But Regenbogen-Weiss reminds them of the airplane safety instructions about securing your oxygen mask first.

“You are no good to your care partner if you don’t take care of yourself,” she says.

To do that, caregivers should remember these self-care tips:

● Always make time for your own medical screenings and appointments. Tell medical providers that you’re a caregiver so that they’re aware of the impact caregiving may have on your health.

● Incorporate timeouts from caregiving throughout the day, whether you take 15-minute walks or meet a friend for lunch.

● Practice relaxation techniques for a few minutes each day. Take slow, deep breaths you can feel in your belly, or close your eyes and try to focus on your body and your breath.

● Be mindful of your moods, and know that all caregivers experience feelings of impatience and frustration, among other strong emotions. Consider seeing a counselor or joining a support group.

● Caregivers often feel that their efforts are never enough. Be kind to yourself. Don’t forget to give yourself credit for your contributions.

The Caregivers Service, part of the HealthOutreach program at NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center, offers two support groups that are free and open to the public: one for those caring for patients with Alzheimer’s disease and other cognitive impairments, and one for caregivers of anyone older than 60 with chronic illness. Nancy Viola, a licensed master social worker, facilitates both groups.

The groups provide a forum for sharing practical advice as well as topics that can be uncomfortable to discuss, like anger, resentment, and the intimate tasks of caregiving.

“People in the groups often say they don’t want to burden others with their caregiving concerns within casual conversation,” Viola says. “They fear that someone not in that role wouldn’t understand.”

The Caregivers Service also offers the Caregiver Resource Line, referrals to community resources, educational workshops, and individual consultations with social workers. Regenbogen-Weiss says the Caregivers Service welcomes inquiries, whether caregivers are looking for information or simply someone to talk to.

There are also programs and support groups for caregivers of children who are ill and currently in the hospital. The Family Advisory Council at NewYork-Presbyterian Komansky Children’s Hospital provides parent lunches, teas, and meet-ups to help families cope during their child’s hospital stay. During or following a child’s stay, caregivers are offered a unique form of support through the Parent-to-Parent Mentoring Program, where they can speak by telephone with a caregiver who has gone through a similar experience. This one-to-one interaction provides emotional support to both current and former families of children cared for at Komansky.

Similarly, the Family Advisory Council at NewYork-Presbyterian Morgan Stanley Children’s Hospital offers children and families the resources they need to have a better hospital experience. One such resource is the sibling program — Charna’s Kids’ Club — where siblings of inpatient children can interact with peers and participate in activities that create a safe place for expression and social support, including creative play, art, crafts, dance, group games, and homework help.

“What is really important for caregivers to realize is that they don’t have to do this alone,” says Regenbogen-Weiss.

For more information on the HealthOutreach program, visit here.