It Happened Here: Dr. Elizabeth Blackwell

How the nation’s first female doctor changed the face of medical care.

When Elizabeth Blackwell was a 24-year-old teacher, she visited a close family friend dying of uterine cancer who spoke of how she had suffered at the hands of male doctors during her medical treatment.

“Why not study medicine?” the friend asked. “If I could have been treated by a lady doctor, my worst sufferings would have been spared me.”

Elizabeth immediately rejected the idea. “I hated everything connected with the body and could not bear the sight of a medical book,” she wrote in her autobiography, Pioneer Work in Opening the Medical Profession to Women.

But the spark was lit. In 1849, she become the nation’s first female doctor. Eight years later, she founded the first U.S. hospital staffed entirely by women, which eventually evolved into today’s NewYork-Presbyterian Lower Manhattan Hospital. And in 1868, she launched a medical college devoted entirely to the medical education of women, which was absorbed by what is today Weill Cornell Medicine.

“Dr. Blackwell is an inspiration to all women physicians,” says Judy Tung, M.D., chair of the department of medicine at NewYork-Presbyterian Lower Manhattan Hospital and associate professor of clinical medicine at Weill Cornell Medicine. “She has reminded us never to forget the roots of why we came into medicine: to serve the people.”

Determined and Focused

Elizabeth was born in 1821, in Bristol, England, one of nine children. Her father, who owned a sugar refinery, was active in the anti-slavery movement and wanted his daughters to have the same educational opportunities as their brothers. In her autobiography, she described her childhood as “very happy years, rich and satisfying.”

When she was 11, after the sugar refinery burned down, the family moved to America in pursuit of business opportunities and progressive ideas. They spent the next six years in New York City and the suburbs of Long Island and New Jersey. Elizabeth attended school and threw herself into the abolitionist movement, attending anti-slavery meetings and sewing for abolitionist fundraising fairs.

In 1838 at age 17, with her father’s new sugar refinery struggling, business prospects lured the family to Cincinnati. They were “full of hope and eager anticipation,” she wrote. But within a few months of arriving, her father died, leaving the family penniless.

To support the family, Elizabeth and her sisters opened a young ladies’ day and boarding school. They closed it after a few years, and Elizabeth went on to teach in several states. It is during this time that she had the meeting with the dying family friend that changed her life.

“The idea of winning a doctor’s degree gradually assumed the aspect of a great moral struggle,” she wrote in her memoir, “and the moral fight possessed immense attraction to me.”

Her teaching jobs took on new meaning: to earn money to fund her education. She took a post teaching music in South Carolina, where she boarded with the family of a distinguished physician who gave her access to his vast medical library, and she spent all her spare time studying.

Soon, she applied to more than 20 medical schools and “was not surprisingly rejected by them all,” Dr. Tung says. “Fortunately, she had a mentor,” an esteemed physician, who wrote a letter on her behalf to Geneva Medical College in upstate New York.

On October 20, 1847, Elizabeth received an acceptance letter that became one of her most cherished possessions. The letter explained that her acceptance had been put to a vote before the entire medical class, which voted affirmatively. “Legend has it,” Dr. Tung says, “they thought it was a joke.”

Listen to how Dr. Blackwell fought her way into anatomy class

But Elizabeth took her studies seriously, earned the respect of her colleagues (though she had to persuade them to allow her to attend anatomy class), and graduated at the top in her class. She was the first woman to graduate from a U.S. medical college.

On graduation day, the town turned out to the packed ceremony and fell silent when Dr. Blackwell was called up last to receive her diploma. “It shall be the effort of my life, by God’s blessing, to shed honor on this diploma,” she said. The crowd burst into applause.

Helping Other Women Succeed

She continued her training at La Maternité, a large maternity hospital in Paris. One day, when syringing the infected eye of a baby, the fluid spurted into Dr. Blackwell’s eyes. Despite an intensive treatment that included leeches and cauterizing the eyelids, she went blind in her left eye, which had to be surgically removed. Her plan to become a surgeon was thwarted.

Returning to New York in 1851, Dr. Blackwell opened her own general medical practice but found it hard to find patients since many didn’t want to be treated by a woman. Upon applying to work in the women’s department of a large city clinic, called a dispensary, she was rejected by her potential employers and told to form her own.

“A most extraordinary case!” Listen to how a male doctor reacted to a woman physician

Dr. Blackwell did just that. In 1854, she founded the New York Dispensary for Poor Women and Children near Tompkins Square, where an impoverished immigrant community that lacked hot water and indoor toilets, and battled outbreaks of typhoid, diphtheria, and other diseases, resided. In the one-room clinic, which was funded in part by a group of local Quakers, she provided free healthcare to women and children who couldn’t afford it.

That same year, feeling lonely and isolated, she adopted a 7-year-old Irish girl, Kitty, from an orphanage on Randall’s Island. Kitty lifted Dr. Blackwell’s spirits. “I feel full of hope and strength for the future,” Dr. Blackwell wrote one sunny Sunday as Kitty played beside her with a doll. “Who will ever guess the restorative support which that poor little orphan has been to me?”

To further provide medical and surgical care for poor families and a pathway for other women physicians, Dr. Blackwell set out to open a hospital staffed entirely by women.

“This first attempt to establish a hospital conducted entirely by women excited much opposition,” Dr. Blackwell wrote in her autobiography. “At that date, although college instruction was being given to women students in some places, no hospital was anywhere available either for practical instruction or the exercise of the woman-physician’s skill. To supply the need had become a matter of urgent importance.”

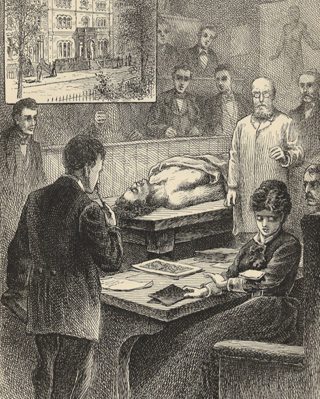

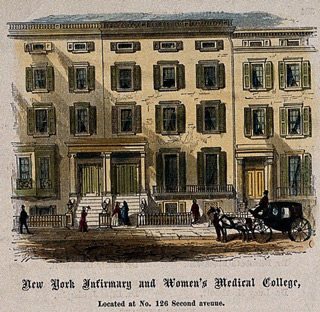

The New York Infirmary for Indigent Women and Children opened on May 12, 1857. Supported by donations and fundraising, the hospital was run by Dr. Blackwell, her younger sister Emily, who had become a surgeon, and a third physician. Four medical students and two nurses soon joined the staff.

Listen to Dr. Blackwell’s words on why opening a hospital staffed entirely by women became a matter of “urgent importance”

“She opened her own hospital by women physicians, for women and children,” says Juan Mejia, senior vice president and chief operating officer at NewYork-Presbyterian Lower Manhattan Hospital. “Not only was she brave enough to chase her own dreams of becoming a physician, she wanted to make that dream possible for other women.”

A decade later, Dr. Blackwell opened a medical school devoted entirely to training women. Adjacent to the infirmary and working closely together, the Women’s Medical College of the New York Infirmary became one of the first four-year medical colleges in the country. Having earned a reputation for its rigor and excellence, after three decades it became part of what is today Weill Cornell Medicine, which agreed to take all its students.

Dr. Blackwell also played a major role in the Civil War, establishing an association to coordinate the training of nurses for the battlefield and the collection of supplies. It evolved into the United States Sanitary Commission, approved by President Abraham Lincoln, whom she met when she visited him in the White House.

Afterward she dashed off a letter to her daughter, Kitty: “A tall, ungainly loose-jointed man was standing in the middle of the room. He came forward with a pleasant smile and shook hands with us. I should not at all have recognized him from the photographs — he is much uglier than any I have seen. … Then he plumped his long body down on the corner of the large table …, caught up one knee, looking for all the world like a Kentucky loafer on some old tavern steps, and began to discuss some point about the war.”

In 1869, she left the infirmary in the hands of her sister Emily and returned to England. There, Dr. Blackwell had already become the first woman on the British Medical Register, which was required for practicing medicine, and had inspired Elizabeth Garrett Anderson to become England’s first qualified woman doctor. Dr. Blackwell continued to advocate for women in medicine, lecturing and writing. She died in 1910 at age 89.

Dr. Elizabeth Blackwell

Infirmary Carries On

The infirmary continued on for more than a century, including many decades when it was staffed almost entirely by female physicians.

Initially, the hospital charged $4 a week and provided free care to those who couldn’t afford it. Dr. Blackwell championed the importance of hygiene and prevention and established the “sanitary visitor” who would go to the poorest neighborhoods to teach families about cleanliness, fresh air, and healthy food. (Dr. Blackwell served as professor of hygiene at the medical college.)

Eventually, the infirmary became a general hospital serving the general public, its name shortened to the New York Infirmary. During its first 100 years, it cared for more than 1 million men, women, and children, according to a book by the New York Infirmary that celebrated its century of service.

The infirmary eventually evolved into what is today NewYork-Presbyterian Lower Manhattan Hospital, home to hallway murals depicting the infirmary and dispensary; a street corner named “Dr. Elizabeth Blackwell Place”; and Dr. Blackwell’s writing desk from Bristol, England. But, Mejia says, Dr. Blackwell’s influence runs even deeper.

“Dr. Blackwell’s legacy lives on in our hospital,” Mejia says. “Her social consciousness lives on in our commitment to women and children and the diverse and vibrant communities that we serve. And her leadership lives on in our women physician leaders making a difference here at NewYork-Presbyterian Lower Manhattan Hospital.”

Among them is Dr. Tung.

“Elizabeth Blackwell’s legacy is very much alive in this hospital,” she says, adding: “Elizabeth Blackwell has personally inspired me in so many ways. As a primary care doctor, I admire her social consciousness and commitment to caring for the underserved. Her paving the way for an entire future generation of women is the reason why I’m privileged to be here today.”

Featured illustration credit: Josephine Truslow Adams