Getting Support to Survivors Right After Their Opioid Overdose

NewYork-Presbyterian participates in the Relay program, which delivers lifesaving resources at a time when they may do the most good.

Michael* had been using cocaine regularly for a little over half a year but said he had stayed away from heroin, even though he was selling it. One night in spring 2018, however, this changed. After Michael and his wife had finished the last of their cocaine, he wanted to stay high, so he decided to try some of his heroin stash. After sneaking off and snorting two small scoops — or “bumps” — in his Upper Manhattan apartment, he went to lie down.

The next thing Michael remembers is a paramedic in his face. Although it was the first time he said he had tried the drug, he’d overdosed.

“Basically, one good time could be the end of the line,” Michael says of the experience that nearly killed him.

His wife found him in their bedroom, his throat swelling, his lips turning blue. She called 911. Paramedics revived Michael with two doses of naloxone, the opioid overdose rescue drug, as his two daughters, ages 3 and 4, peeked through the bedroom door.

An ambulance rushed Michael to NewYork-Presbyterian Allen Hospital’s emergency department, where he was stabilized and admitted. Doctors then made a phone call that may have saved Michael’s life. They called Relay, a program that sends peer advocates to meet with opioid overdose survivors at participating emergency departments and connects them to support services.

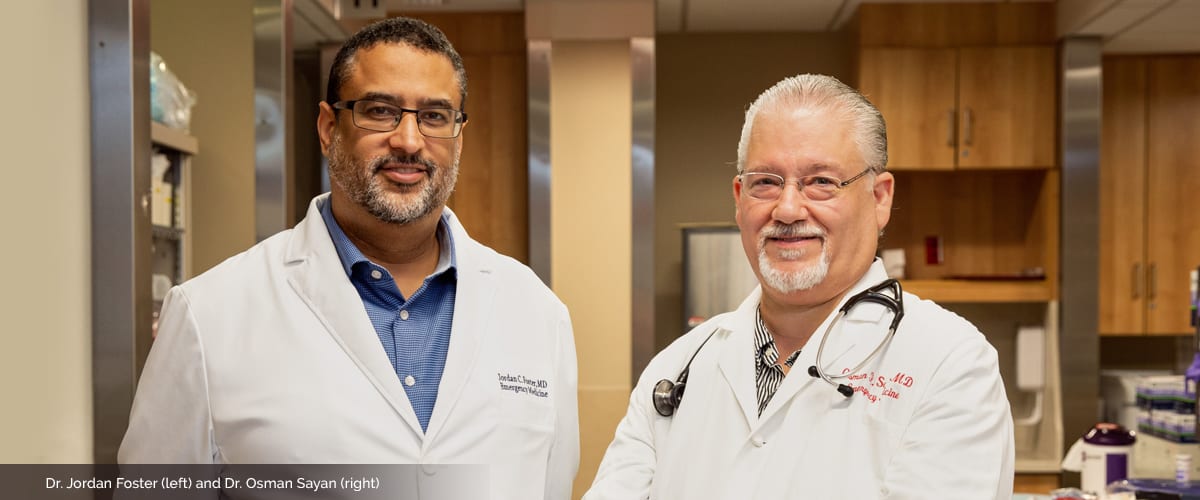

NYC Health Department wellness advocate Ben “Big Ben” Mushlin and Dr. Osman Sayan

While Michael was recovering, a 6-foot-4-inch man wearing a bright blue New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene jacket and a friendly smile came to check on him. Ben Mushlin, or “Big Ben” as he’s known, was ready to talk to Michael about making changes to prevent another near-death experience — or worse.

“That day I almost lost my life,” Michael says. “I love my kids and I definitely wasn’t trying to leave them behind. I thought, ‘Maybe this person can help me out.’ So I gave it a shot.”

The Relay Program

Relay was launched by the New York City health department in spring 2017, and NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving Medical Center became the first hospital to offer the service. In March 2018, NewYork-Presbyterian Allen Hospital began offering Relay as well.

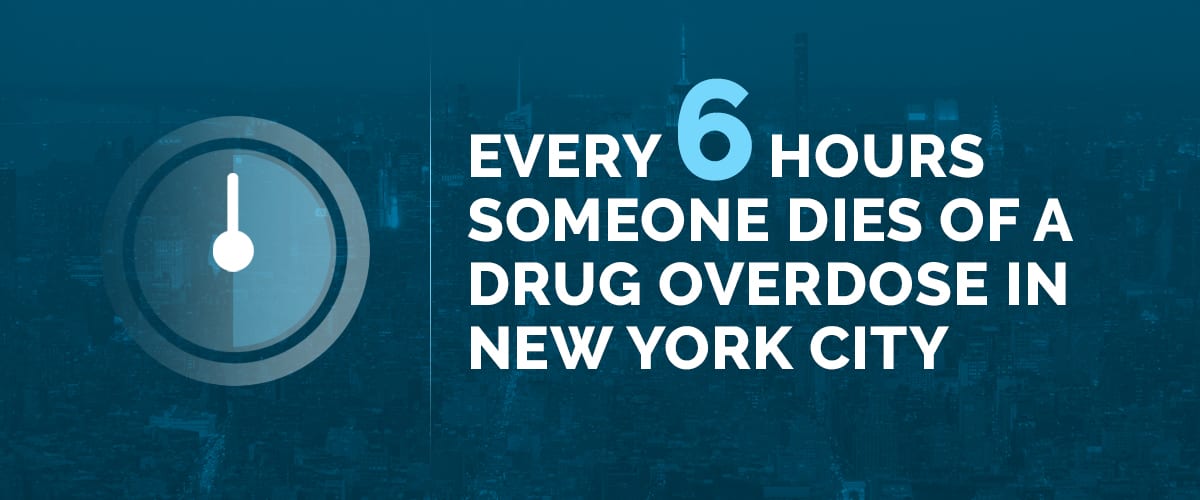

“This could be a moment when people who are addicted would now have a motivation for behavioral change,” says Dr. Jordan Foster, director of government and community affairs for emergency medicine at NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving Medical Center and NewYork-Presbyterian’s liaison to the Relay program. “We wanted to make it as easy as possible to minimize whatever barriers there are for people to get to the next step, whether it’s a program or support services so they can deal with their addiction issues.”

Here’s how it works: Once a patient who has experienced an opioid overdose arrives in the emergency department and Relay is called, a “wellness advocate” or peer who has had personal experience with substance abuse, like Ben, arrives within the hour. These advocates offer patients everything from naloxone kits to keep on hand to referrals to medication-assisted treatment like methadone and buprenorphine, and social services such as housing, food assistance, or health insurance. Patients can work with the wellness advocate for up to 90 days.

Relay aims to use the critical window of opportunity in the hours after a near-death experience to offer help. With survivors of an opioid overdose two to three times more likely to experience a fatal overdose than people who use drugs but have not experienced an overdose, the goal of the program is simple: to save lives.

Relay now operates at seven emergency departments at hospitals across the city and will expand to 15 by June 2020. Since Relay’s launch, 157 overdose survivors from the two NewYork-Presbyterian hospitals and 620 people citywide have chosen to participate in the 24/7 program, which targets hospitals serving communities with the highest opioid overdose death rates.

“Opioid addiction cuts across all socioeconomic classes, all education levels, and all races,” says Dr. Philip Wilner, senior vice president and chief operating officer of NewYork-Presbyterian Westchester Division, who also oversees NewYork-Presbyterian’s efforts to address the opioid epidemic. “Relay is an important part of our strategy to engage with those suffering from addiction so we can help them find ways to deal with their drug use, connect survivors to lifesaving support, and loosen the grip of overdose deaths that has been strangling our city.”

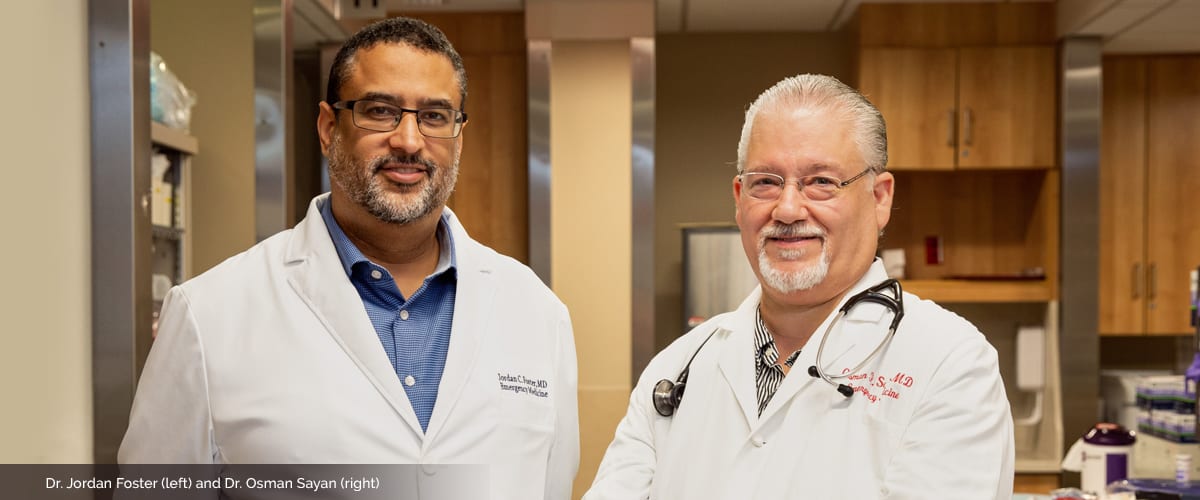

NewYork-Presbyterian is also educating staff on how to take a more sympathetic approach to patients who have an addiction, focusing on non-opiate pain relief options, and collaborating with community-based organizations to get people treatment, Dr. Wilner says. Additionally, NewYork-Presbyterian has been conducting training sessions with members of the public on how to use naloxone and giving away free kits with the lifesaving drug.

“Given the current opioid epidemic, we all need to know how to use naloxone,” says Dr. Jonathan Avery, director of addiction psychiatry at NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center, who runs NewYork-Presbyterian’s community naloxone trainings. “It is a safe, easy-to-administer medication that saves lives, and you can’t hurt someone by using it even if they haven’t had an opioid overdose.”

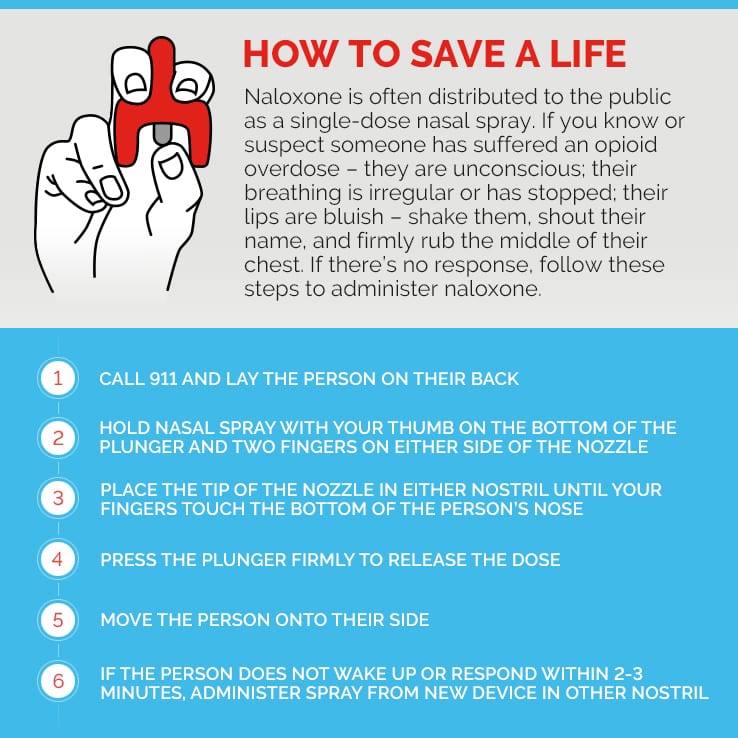

An Epidemic of Overdose Deaths

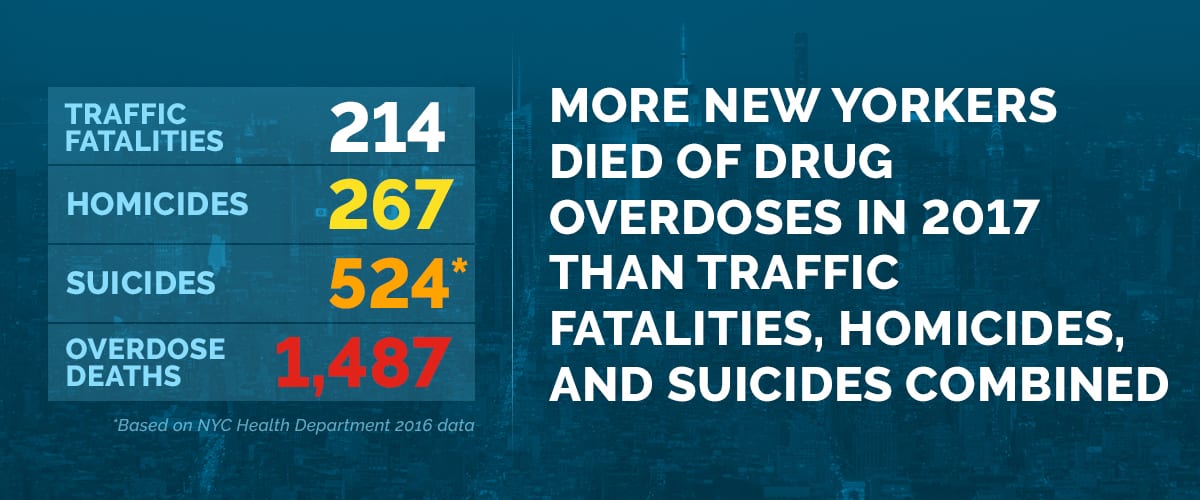

Overdose deaths are at epidemic levels in the United States. Unintentional drug overdoses killed more than 70,000 Americans in 2017, a 10 percent increase over 2016, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. New York City experienced the highest number on record, with 1,487 unintentional drug overdose deaths in 2017, compared with 942 in 2015, according to the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. Every six hours a person dies from an overdose in New York City, and more than 80 percent of those deaths involve opioids.

“Approximately one quarter of the deaths in our emergency department are from opioid overdoses,” says Dr. Foster. “Before, it was definitely more of a mixed bag of deaths, with overdoses occurring not very often.”

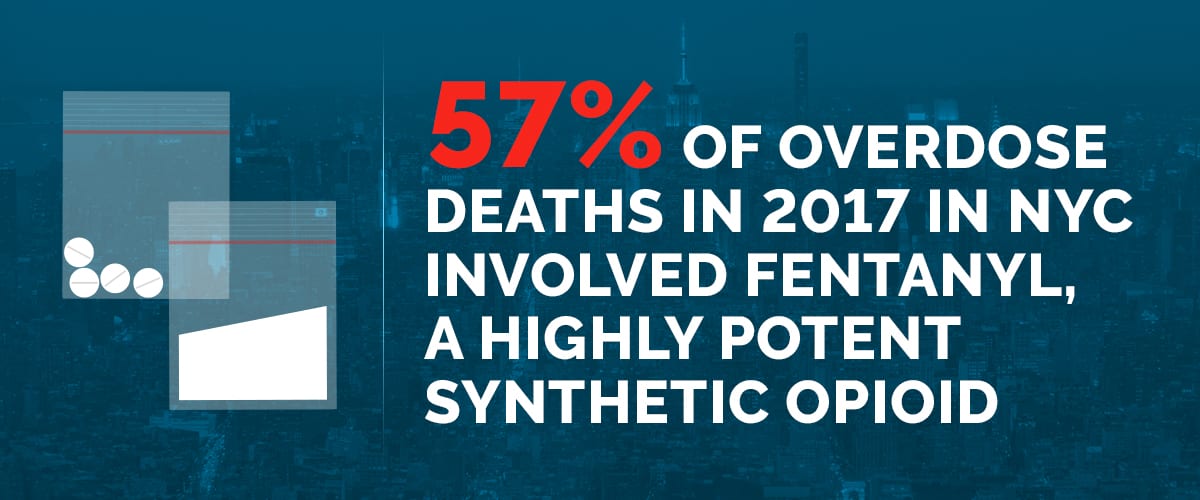

Perhaps most frightening, people who use drugs may not know that some of these drugs contain fentanyl, a potent synthetic opioid that can be laced into heroin, cocaine, or pills. Fentanyl was involved in 57 percent of overdose deaths last year in New York City, according to the health department.

“Fentanyl is dirt cheap, so it’s being mixed with anything that’s a white powder,” Dr. Foster says. “It’s almost a pride among the dealers that what they have is deadly, that somehow that means it’s strong and worth the money that you’re going to spend for it. It’s resulted in skyrocketing deaths from drug users who don’t even know what they’re taking. And we’re seeing it weekly here in the emergency department.”

One Night in the Emergency Department

The opioid crisis was evident one recent night in the emergency department at NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving Medical Center, when paramedics brought in four drug emergencies.

Ranging in age from 22 to 41, two patients were men, two were women. All had used heroin, and one had injected both cocaine and heroin, known as speedballing. Paramedics had given the patient in the most serious condition 8 milligrams of the rescue drug naloxone, approximately 20 times the amount typically given. The patient had been found unresponsive, lying on their back, and vomiting. In the emergency department, doctors suctioned the vomit from the patient’s mouth, started oxygen and monitored breathing. Because it was likely that vomit had entered the lungs, causing inflammation, the patient was admitted for observation and treatment. The other three were closely monitored for breathing and oxygen, as well.

“With opiate overdoses, you get super-sedated and then may stop breathing,” explains Dr. Osman Sayan, the emergency department attending physician working the overnight shift when these cases came in and the associate program director of the Emergency Medicine Residency at NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital. “We stabilize their breathing, then make sure no other medical issues or physical injuries are present. We monitor their breathing, blood pressure, and pulse until they metabolize the opiates and hopefully wake up. In extreme cases where naloxone does not work, we have to place them on mechanical ventilators until the opiates wear off.”

Drs. Sayan and Foster, who have worked in the emergency department 25 years and 20 years, respectively, have seen a spike in these kinds of overdoses in recent years.

“With the recent trend of mixing heroin with the potent opiate fentanyl,” Dr. Sayan says, “what we’re seeing is the death of young people who are not even making it to the emergency department to get any kind of care because they’ve stopped breathing for too long.”

Support for Overdose Survivors

Ben Mushlin was the Relay peer advocate on call that night. The hospital had called for two patients, but by the time Ben arrived, four were eligible for Relay. Ben waited until the patients were awake.

“We will wait in the ED for however long it takes for the patient to be coherent enough to receive what we’re saying or to consent to our program,” Ben says. “So we’ll wait three hours, six hours, 12 hours — we’ll wait as long as we have to, to speak to somebody.”

Once the patient is awake, the wellness advocate introduces themselves and offers a naloxone kit with two nasal spray doses of the lifesaving medication. If family or friends are with the patient, they’ll get a kit too, along with training on how to administer the medication and where to get more. Citywide, more than 900 naloxone kits have been distributed through Relay, with 60 percent of recipients saying it was their first time receiving a kit.

The NYC Health Department care bag includes two naloxone nasal sprays, among other helpful items

Wellness advocates will also give the patient a care bag of items many of them need: socks, a bottle of water, lip balm, a granola bar, a toothbrush and toothpaste, literature about fentanyl, a list of syringe exchange programs, and a round-trip Metro card.

After this initial encounter, the wellness advocate will try to begin a conversation and see what kind of help the individual needs. The outcome Ben hopes for during his bedside visit is for a patient to consent to work with him for 90 days so he can provide them with vital information and connect them to services, such as a syringe exchange program, and offer tips to reduce overdose risk, such as avoiding mixing drugs, or suggesting they use a small amount first to see how strong the drugs are. These steps help reduce the chance a person will end up back in the emergency department or become a statistic.

Wellness advocates, Ben adds, are just that — advocates. If the person needs help getting mental health counseling or finding housing, “I will help them achieve that.” If asked, wellness advocates will accompany patients to appointments. They sign a HIPAA permission form so Ben can visit them if they are hospitalized; he once was the sole visitor to an overdose survivor who spent months in a hospital behavioral health unit.

“We want to make our interactions as patient-centered as possible,” Ben says, “meaning we want to meet them where they’re at.” There’s no “cookie-cutter approach,” he explains, so while some patients may be open to a detox program, others may not.

“We are a harm reduction program,” he continues. “We don’t follow a typical abstinence base, meaning we’re not gonna tell you to stop using drugs if you’re not ready to. We’re going to give you tips on how to use more safely to reduce the likelihood of another overdose and connect you to supportive services in the community.”

When Ben was called to NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia to see the four patients, two consented to work with him, two did not. All four got naloxone kits.

“I’m not here to tell a person how to live their life,” Ben says. “I’m here to help a person get the things they need to change a behavior that could kill them.”

A Brighter Future

All the motivation Michael needed to stop using cocaine and selling heroin, he says, was his overdose.

“That’s the reason I quit,” he says, citing his wife and three children as his inspiration. “Too many people rely on me for that stupidness [to go on].”

During the 90 days that Ben and Michael worked together, what he needed most, Michael says, was someone to listen. They met weekly at a fast food restaurant to talk.

“If I was having a bad day, I would just let him know, tell him what’s going on, and he would give me advice and just talk to me because I had a lot going on,” says Michael.

“I’m always skeptical to tell someone my private business, especially the negative stuff,” he adds, touching an unlit cigarette tucked behind his ear as his spotted brown puppy played at his feet. “Ben felt easy to confide in. He’d say, ‘You’re doing good, stay focused,’ and that was good motivation.”

In addition to motivation, Michael credits Ben with helping guide him toward a new career, barbering school, and finding financial resources for it. Michael, who enjoys cooking big family dinners, also would like to work toward starting a nonprofit that cooks and serves gourmet food at homeless shelters. Having spent time with his children in the shelter system, he knows how a good meal “can put a smile on your face.” Ben worked with Michael to research what resources were available that could help Michael achieve his goals.

Ben also helped Michael deal with his past. He had kept his drug use a secret from his mother, who lives with the family, and when he overdosed, he told her he was severely dehydrated.

“It’s real embarrassing when you come home and my daughter was like,” he pauses, collecting his thoughts. “It’s tough for me to get out, it was like, ‘Daddy, remember when the doctors had to bring you back from the dead?’”

Michael regrets the choices he made, but also believes the overdose and meeting Ben was, in many ways, an opportunity for change.

“It was a big mistake,” Michael says of his past behavior. “I wish that never happened, but I’m glad it did happen. If it didn’t, I’d probably still be sniffing coke and who knows what would have happened. Everything happens for a reason, I believe.”

*The name of the patient has been changed to protect his privacy

For more information on naloxone, including where to find it for free, please visit: nyc.gov/health/naloxone