Fixing a Little Boy’s ‘Swiss Cheese’ Heart

Born with more than a dozen holes in his heart, Maverick Waler was on the path toward transplant, until he traveled across the country to NewYork-Presbyterian Morgan Stanley Children’s Hospital, where specialists saved his heart and gave him the chance for a normal life.

When the pediatric cardiologist walked into the room with a red clipboard, a notepad, and a diagram of her baby’s heart, Ellyn Waler’s own heart dropped. Ellyn, a human resources director who lives in Redmond, Oregon, was seven months pregnant and everything had been going smoothly. But something did not look right in her last ultrasound.

After another ultrasound, Ellyn and her husband, Brad, an information technology technician, got the news that would start them on a four-year medical journey that ultimately led them 2,800 miles from their home to NewYork-Presbyterian Morgan Stanley Children’s Hospital.

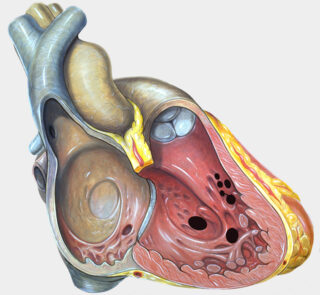

That day, the cardiologist explained to the Walers that the left side of their unborn son’s heart was small, and his mitral valve, which helps keep blood flowing in the right direction, was too narrow. They later found even more issues: multiple holes in the septum, or wall, that separates the right and left sides of the heart, a very rare condition known as a Swiss cheese defect.

Dr. Christopher Petit

“Typically, there’s a solid wall between the right and the left side of the heart,” explains Dr. Christopher Petit, chief of the Pediatric Cardiology Service at NewYork-Presbyterian Morgan Stanley Children’s Hospital. “It’s very common to have a hole in that wall, called a ventricular septal defect (VSD). When there are multiple holes between the wall that separates the two chambers of the heart — holes in different locations and that are different sizes and shapes — that’s what is known as multiple complex muscular VSDs. We use the term Swiss cheese to describe the condition, but even the term doesn’t really do it justice, because the muscle of the ventricles are like a mesh of fibers, so it makes it very complex to locate all the holes and to fix.”

Ellyn’s doctors advised that she give birth three hours away from their home at a larger hospital in Portland, Oregon, because the baby would need open-heart surgery soon after birth.

“You go through a grieving process a little bit, because you have your idea of what delivery is like, what bringing him home is like, and then it’s all sort of thrown up in the air. Because now, everything is different,” Ellyn says.

A Challenging Start to Life

Maverick was born on June 14, 2017, when a scheduled C-section turned into an emergency C-section after his heart rate dropped. Ellyn got a quick glimpse of Maverick before he was whisked away to the NICU, where he could get oxygen. Once the team stabilized Maverick, she was finally able to get a closer look at her baby. “He had this super dark head of hair, and he was all red and chubby,” she remembers.

But by the next day, Maverick’s condition took a turn for the worse due to his heart defect and several infections. Soon he was on medication, intubated, and needed a blood transfusion. He had so many lines running out of his little body that Brad and Ellyn could not hold him.

Born with multiple holes in his heart, Maverick spent the first six weeks of his life in the hospital and was so fragile that his parents could not hold him.

After his birth, doctors were able to get a clearer picture of Maverick’s heart condition. Maverick’s Swiss cheese heart had holes in the upper chambers, called atrial septal defects (ASDs) and VSDs in the lower chambers. Multiple holes are rare, and holes where many of Maverick’s were located, in the apex of the heart, known as apical VSDs, are rarer still.

His heart condition was making Maverick very sick. In a normal heart, oxygen-rich blood enters the left side of the heart from the lungs and goes out to the body while oxygen-poor blood enters the right side from the body and goes out to the lungs. The pressure on the left side is five times higher than on the right. With a porous wall like Maverick’s, the blood can mix, making the overall oxygen saturation level drop, and the pressure in the two sides equalizes, endangering the lungs and other organs.

“The holes have a cascade effect that leads to the damage of other organs,” explains Dr. Emile Bacha, chief of the Division of Cardiac, Thoracic, and Vascular Surgery at NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving Medical Center and director of Congenital Pediatric Cardiac Surgery at NewYork-Presbyterian Morgan Stanley Children’s Hospital. “So, it’s something you really don’t want to happen.”

Two weeks after birth, Maverick underwent surgery to fix a narrowed aorta and install a pulmonary artery (PA) band to regulate the blood flow between his heart and lungs, a temporary fix. After six weeks total in the hospital, the couple finally brought Maverick home — along with an IV pole, a basket full of meds, wound-care material for the surgery wounds in his chest and back, a nasogastric feeding tube he’d rely on for six months, and a long list of instructions. “We were just trying to absorb all the new medical terms we had never heard before and learning how to care for him,” says Brad.

The immediate challenges were daunting enough; the ones looming down the road were too difficult to fathom. Doctors told them that Maverick would probably outgrow his PA band in a year. Then he’d need a number of procedures culminating in the Fontan procedure, an operation that would replumb his heart into a single ventricle, leaving him to live with half a working heart. As a young adult, he’d need a heart transplant.

The Journey to a Cure

Despite all his challenges, Maverick developed into a happy baby, a mellow observer his parents could take anywhere. The medical interventions had put him behind developmentally, but with the help of speech, food, physical and occupational therapies, he caught up to his peers by the age of 2 ½.

When Maverick was 2 and went back to Portland to have a stent inserted into a large ASD ahead of the anticipated Fontan procedure, doctors couldn’t find the hole. While the VSDs remained, the ASDs seemed to be closing on their own. His doctors decided to put off further intervention for a while. Projected to last a year, his PA band was still holding up after three.

Even though Maverick struggled with stamina issues — he couldn’t keep up with other kids on the playground and sometimes had to be carried when he was too tired to walk — he was a typical preschooler in most ways: he loved planes and race cars, cartoons, and playing at the park. He loved to ask why.

Then, in the summer of 2021, his blood oxygen levels started a steady decline, including instances when they would dip alarmingly. One of his cardiologists at home decided to reach out to Dr. Bacha, who had pioneered a successful technique for closing a Swiss cheese septum defect.

Dr. Emile Bacha

Earlier in his career he had repaired a Swiss cheese septum by teaming with a pediatric cardiologist who used a catheterization device to expose and close some of the holes while he surgically patched the others. Dr. Bacha had tackled about 20 Swiss cheese septa cases in his career. But he had never seen a case with as many apical VSDs as Maverick had. “That’s an area that’s sort of a no-man’s-land for surgeons,” says Dr. Bacha. “It’s very, very difficult to get to without damaging the heart.”

By the fall, Maverick’s situation was growing dire. As his oxygen rates dipped, he’d get dizzy and stumble or fall. He complained of headaches and vomited frequently. He needed extra layers to stay warm. “It was clear that he was at the end of the rope,” says Dr. Bacha. “His oxygen saturation was dropping significantly. His PA band was getting very tight, because he was growing into it, and he was having these dizzy spells. His heart just wasn’t functioning correctly.”

But Dr. Bacha had good news for the Walers: After reviewing all his imaging, he thought he could close all of Maverick’s holes. Every other procedure that had been proposed for the boy had been palliative, a way to buy time. No one had said they could actually cure him, until now.

“Our first time talking to Dr. Bacha, he was very confident, and said, ‘Yes, I can fix this,’” says Brad. “It was a very different demeanor from our past experiences when we just understood the procedure as being very complicated. But Dr. Bacha told us, ‘Get out here and we’ll make it happen.’ And so that’s what we did.”

A Successful Outcome Using an Innovative Approach

The family left for New York on December 5, 2021. Maverick was thrilled with the prospect of being on two big planes in connecting flights and taking a taxi ride. But he had a lot of questions once he arrived. With his parents showing him surgery and MRI videos and the Child Life staff at NewYork-Presbyterian Morgan Stanley Children’s Hospital demonstrating procedures in a child-friendly way — Maverick still has the teddy bear he watched get an IV — the boy was well-informed and prepared when, holding a nurse’s hand, he went in for his surgery on December 13.

Working alongside Dr. Petit and utilizing a hybrid approach, Dr. Bacha and the surgical team operated on Maverick for more than six hours to remove the PA band and close more than a dozen holes, some as big as a dime.

Patients who have Swiss cheese VSDs have multiple holes in the wall that separates the two chambers of the heart. Maverick’s surgery required a hybrid approach between Dr. Petit and Dr. Bacha to find and repair the holes in his heart.

“When kids have this type of heart disease, it’s really challenging because you can’t just say, ‘I’ll close all the holes with patches,’” says Dr. Petit, who is also chief of the Division of Pediatric Cardiology in the Department of Pediatrics at Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons. “Sometimes you can’t even find the true hole because it’s not really one single hole. It’s pathways that are covered in a network of fibers that are all in disarray. Think of four or five of these layers of these fibers that make it almost impossible to identify holes, which is why we use this combined approach of me with the devices, which go through the hole and have a double umbrella, and Dr. Bacha closing the other ones with the patch.”

Says Dr. Bacha, “You need to have two disciplines. We need cardiac surgery and cardiology working together. But it really takes a village. The team in pediatric cardiac surgery did a great job. But then also you have to have anesthesia, perfusion, nursing, cardiology, the ICU nursing, social workers, the respiratory therapist. The team that took care of Maverick was amazing.”

The Greatest Gift: A Normal Life

When Dr. Bacha came to talk to Ellyn and Brad in the waiting room following the surgery, he had the best news he could possibly deliver to the anxious parents. Despite its complexity, the surgery had gone better than he could have hoped. Not only that, when Brad asked if Maverick would need further surgery later, Dr. Bacha said no. The boy wouldn’t need a heart transplant, or any major heart surgeries ever again.

“I’m happy to say that his prognosis is outstanding,” says Dr. Bacha. “He’s back to the normal life expectancy curve with a normal quality of life.”

An airplane enthusiast, Maverick celebrated his 5th birthday in June on a retired Air Force cargo plane.

Ellyn wanted to scream and dance. “It felt like we were weightless walking on clouds,” she says. “It was the best Christmas present ever. He gets to play soccer, he gets to run out in the snow without his coat on, all those things we worried about. He gets to just grow up and be himself. It was amazing. We are so grateful to Dr. Bacha and the entire team.”

Six months out from surgery, Maverick still loves trains and planes and race cars, and he’s still funny and inquisitive. But he has grown bigger and faster. Now he runs — all the time, without getting tired. One of his great disappointments before heart surgery was that he could never keep up with a school friend in a foot race. Just weeks after returning from New York, he came home from preschool triumphant. “I beat him!” he announced. “It’s because of my new heart!”

Maverick won’t need to visit his cardiologist for another six months and can’t wait to go to kindergarten in the fall. He can already write his name. And there are plans for a big celebration in June when he turns 5: The Walers have rented out a retired Air Force cargo plane at an airport for the party.

“It’s like your heart smiles and you can take this huge, deep breath,” says Ellyn. “We’ve gone from an uncertain future that was scary and full of questions, to a vibrant, energetic life. The future is bright, and we love looking toward the horizon.”