Celebrating Dr. Elizabeth Blackwell: The First Woman in the U.S to Become an M.D.

In honor of National Women Physicians Day, held on Dr. Blackwell’s birthday, a group of NewYork-Presbyterian’s female leaders celebrate the country’s first female physician.

The tradition of pioneering female leaders and women mentoring women is strong at NewYork-Presbyterian, and that foundation was laid by Dr. Elizabeth Blackwell, the country’s first female physician and founder of a hospital that evolved into today’s NewYork-Presbyterian Lower Manhattan Hospital.

Following in Dr. Blackwell’s footsteps, Dr. Geraldine McGinty, assistant attending radiologist at NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center and associate professor of clinical radiology at Weill Cornell Medicine, is proud to be a champion for her fellow female colleagues. “Dr. Blackwell was an incredible mentor to the women who came after her,” says Dr. McGinty. “And it’s been something that I’ve benefited from throughout my career. So I think it’s really important to pay that forward and ensure that you open up opportunities and offer visions of leadership to those who are coming [after you].”

A Pioneer in Medicine

In the 1800s, the notion of a woman becoming a doctor was considered laughable, something Dr. Blackwell experienced firsthand, says Dr. Judy Tung, section chief of Adult Internal Medicine at NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center and associate dean for faculty development at Weill Cornell Medicine. Having emigrated from England in 1832, Dr. Blackwell worked as a music teacher and boarded at a physician’s home. She had access to a vast medical library and became inspired to study medicine, but faced many hurdles in her pursuit of medical school. “[She] got summarily rejected and was actually advised to disguise herself as a man and attend school in Paris,” says Dr. Tung.

Dr. Elizabeth Blackwell was born on February 3, 1821 in Bristol, England.

Dr. Blackwell didn’t heed that advice. Instead, she persisted, and applied to more medical colleges while studying and apprenticing. An eminent Quaker physician who served as her mentor wrote a letter of recommendation to Geneva Medical College in upstate New York, where she became the first woman ever accepted to a medical school in the United States — but not without spectacle. “The dean decided to put her admission decision to a vote of the student body,” says Dr. Tung. “Only a unanimous decision would result in her acceptance. So the story goes that after the dean presented this, the class was seized with laughter and catcalls due to the ludicrousness of the situation. The single ‘nay’ in the room was pummeled until he turned his opinion around and a unanimous decision was returned to the dean — as a joke.”

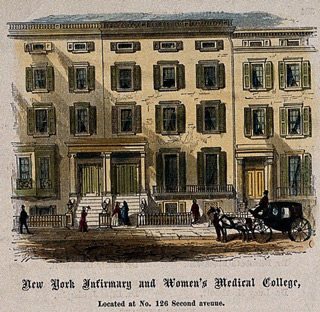

Dr. Blackwell, of course, had the last laugh. In 1849, she graduated first in her class. She won over her male classmates and went on to become one of the most important figures in medicine, establishing the New York Infirmary for Indigent Women and Children (which evolved into today’s NewYork-Presbyterian Lower Manhattan Hospital) in 1857 and opening a medical school for women in 1868 that was absorbed by what is now Weill Cornell Medicine.

Reshaping Patient Care

Dr. Blackwell’s quest to become a physician wasn’t driven by a selfish desire for personal achievement. Her mission from the start was to give back to society — providing care to the most vulnerable populations and ensuring that they were all treated with respect. It is that legacy that NewYork-Presbyterian proudly carries on today.

“Every day we work in the emergency department, we are seeing patients like those Dr. Blackwell took care of … those that weren’t able to pay for their own healthcare,” says Dr. Brenna Farmer, Emergency Department site director at NewYork-Presbyterian Lower Manhattan Hospital and associate professor of clinical emergency medicine at Weill Cornell Medicine. “NewYork-Presbyterian continues the work of Dr. Blackwell, including having people who help our patients navigate the system to get the care they need.”

Illustration of the New York Infirmary for Indigent Women and Children and Women’s Medical College founded by Dr. Elizabeth Blackwell.

Dr. Tung says that it was Dr. Blackwell’s family friend Mary Donaldson who suggested that Blackwell pursue a career in medicine. Donaldson, who likely had terminal uterine cancer, had shared that she would not have suffered as much had a female doctor cared for her, and encouraged Dr. Blackwell to change the way that female patients were treated. After Dr. Blackwell earned her degree, she focused her efforts on serving women and children, doing so for free or on a sliding fee scale.

“When I think about Elizabeth Blackwell, the two words that come to mind are courage and tenacity,” says Dr. Joy Howell, associate attending pediatrician at NewYork-Presbyterian Komansky Children’s Hospital.

Continuing the Work

At NewYork-Presbyterian, female leaders continue to carry the torch not only by providing outstanding care, but also by fostering a culture of mentorship and community within the institution. From Dr. Howell, who serves as assistant dean for Diversity and Student Life at Weill Cornell Medicine, to Dr. Shari Platt, chief of Pediatric Emergency Medicine at NewYork-Presbyterian Komansky Children’s Hospital and Weill Cornell Medicine, who works closely with medical students, trainees, and junior faculty to help them develop as leaders, the female physicians of NewYork-Presbyterian remain committed to cultivating new talent and creating opportunities.

“In my time here, part of my development has been because individuals opened the door,” says Dr. Howell. “There’s no point in anyone’s career where you don’t need mentorship. To go from mid- to senior level, you need strong mentorship.”

Dr. McGinty has seen these strong networks go beyond the walls of the hospital. The support systems for the women of NewYork-Presbyterian uplift them in their careers — and their lives. It’s a ripple effect that extends into society at large. “We need our broad professional network, but we need that squad of people that we can go to in our personal lives as well,” says Dr. McGinty, who won Weill Cornell Medicine’s Jessica M. and Natan Bibliowicz Award for Excellence in Mentoring Women Faculty in 2019. “Why it’s so important for us to become leaders is because then our influence is amplified and we’re able to impact a greater number of people and a greater part of the health system and truly move things in the right direction.”

For Dr. Platt, reflecting on Dr. Blackwell helped put into perspective her own journey and the mark she wants to leave behind. “I took for granted the path that I took without really realizing how difficult it was to pave that way. Having learned more about Elizabeth Blackwell, I’m really grateful for the things that I have in my life as a woman leader,” she says. “There’s absolutely nothing more satisfying and more rewarding than this career. And if there were a young girl who was debating about being a doctor, I [would tell her] that we need strong, smart, intelligent, wise, kind, and compassionate women doctors.”

It’s exactly the sentiment Dr. Blackwell would have affirmed, and these women are living proof that her legacy proudly lives on at NewYork-Presbyterian today.