At 8, a Heart Pioneer

Born with a congenital heart condition known as tetralogy of Fallot, Yasin Samad needed multiple surgeries in the first few years of his life. But thanks to a collaborative effort across NewYork-Presbyterian and an innovative approach, Yasin is a thriving third-grader who's proud to share the story of his heart journey.

Standing in front of his third-grade classroom in Ozone Park, Queens, Yasin Samad prepared to start his presentation. The topic was not history, math, or reading. Yasin, age 8, had created a show-and-tell about his heart.

Just then a special guest, Dr. Maria Thanjan, chief of pediatric cardiology at NewYork-Presbyterian Queens, joined Yasin to talk to the class. Dr. Thanjan, who has cared for him since he was a newborn, had said she was going to join on Zoom with Yasin’s mom, Syema. She surprised him in person instead, and together they talked about Yasin’s condition and presented a slideshow of his journey through three open-heart surgeries — including the fact that he is one of the first kids ever to receive a new kind of artificial valve that helps his heart pump blood to his lungs.

“Dr. Thanjan explained what a real heart looks like and what my heart looks like,” says Yasin. “Everyone was clapping at the end and wanted to take pictures with me. One kid asked, ‘How was your last surgery?’ and I said, ‘It went very well.’”

After the show-and-tell, Dr. Thanjan had another surprise. “She gave us stethoscopes so we could all hear each other’s heartbeats. It was so cool,” he says.

Dr. Thanjan’s interest in cardiology traces back to when she was diagnosed with congenital heart disease at age 5. She remembered the moment her doctor let her listen to her heartbeat, and she wanted Yasin to experience that as well. “It brought tears to my eyes to see Yasin’s eyes light up,” she says. “I really wanted to make him aware of how special he is and how proud I am that he is willing to tell his story to help other people.”

Dr. Maria Thanjan with Yasin, his father Adam and mother Syema.

An Unexpected Diagnosis

Yasin was born on August 24, 2015, at NewYork-Presbyterian Queens after a scheduled C-section. Syema had developed a serious pregnancy condition called placenta accreta that increases the risk of premature birth and hemorrhage. After Yasin was taken to the NICU, doctors noticed a heart murmur and tests showed he had a congenital heart defect known as tetralogy of Fallot (TOF). “It was definitely hard not knowing what to expect, but the care team was really helpful with guiding us through the process,” says Syema.

Cases of TOF range in severity — some babies require immediate surgery, and others, like Yasin, can wait to grow stronger and gain weight. “I met Yasin when he was a newborn,” says Dr. Thanjan. “His oxygen was still normal, but he needed surgery within the first six months of life.”

Yasin, after his first and third open-heart surgeries.

What is Tetralogy of Fallot?

Babies with TOF have four heart abnormalities which together restrict blood flow from the heart to the lungs, so babies born with TOF do not get enough oxygen. About 1 in every 2,077 babies in the U.S. are diagnosed with TOF each year, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

- Pulmonary stenosis: A narrowing of the valve between the lower right heart chamber and pulmonary artery limits blood flow.

- Ventricular septal defect: A hole between the bottom left and right chambers of the heart allows blood to cross from one side of the heart to the other.

- Overriding aorta: The aorta, the main blood vessel going to the body, is positioned over the hole between the left and right chambers instead of over the left ventricle.

- Right ventricular hypertrophy: The muscle wall in the lower right chamber of the heart thickens because the heart is pumping harder than normal, which can make the heart stiff and weak over time

A Team Effort

Yasin’s care required expertise from doctors across NewYork-Presbyterian, who work together on some of the most difficult cases. Twice a week, Dr. Thanjan and other pediatric cardiologists and heart surgeons at NewYork-Presbyterian Komansky Children’s Hospital and NewYork-Presbyterian Morgan Stanley Children’s Hospital discuss patients in a multidisciplinary conference call done over Zoom. “Everyone weighs in, and we come up with a plan,” she says. “If a patient needs a procedure, they can go to either campus, and then they come right back home to me and we follow them in Queens.”

Dr. Emile Bacha, the chief of the Division of Cardiac, Thoracic and Vascular Surgery at NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving Medical Center, performed Yasin’s open-heart surgery. Because Yasin’s case of TOF was less severe, Dr. Bacha kept the pulmonary valve intact and instead widened the pulmonary artery to improve blood flow.

The surgery was successful, but ten months later, when Yasin was 16 months old, his pulmonary valve started to weaken, and not enough oxygen was getting to his lungs. Dr. Bacha did a second operation to relieve the obstruction of blood flow. “We went home in about a week, and Yasin was active, moving and playing,” says Syema. “Nobody could even tell that he had surgery.”

For most patients with TOF, the pulmonary valve lasts until the teenage years before it starts to wear out or leak. But at 7, Yasin started showing symptoms that the valve was failing. “I used to watch Yasin play basketball with his brother and their cousins in the backyard, and he was like the other kids,” says his father, Adam. “Then there was a period of time where I could see that he needed longer breaks, and he would complain that he was running short of breath.”

Dr. Oliver Barry

Groundbreaking Technology

When Dr. Thanjan presented Yasin’s case again to Dr. Bacha, they discussed surgical options to replace the pulmonary valve. For a 7-year-old child, the choices are limited. Artificial valves are built only for adult sizes, and tissue valves (for example from a pig, cow, or human) wear away over time, which meant Yasin would need multiple open-heart surgeries before adulthood.

Because of Yasin’s age, Dr. Bacha recommended he enroll in a national investigational clinical trial for a new device called the Autus Valve. Dr. Bacha and Dr. Oliver Barry, a pediatric interventional cardiologist at NewYork-Presbyterian Morgan Stanley Children’s Hospital, are leading the trial for NewYork-Presbyterian — one of the first three sites in the nation chosen to participate. Children ages 18 months to 16 years are eligible.

“Yasin was a great candidate for this particular valve because any other traditional option would have required him to have yet more surgeries in the future, and we wanted to avoid that,” says Dr. Bacha.

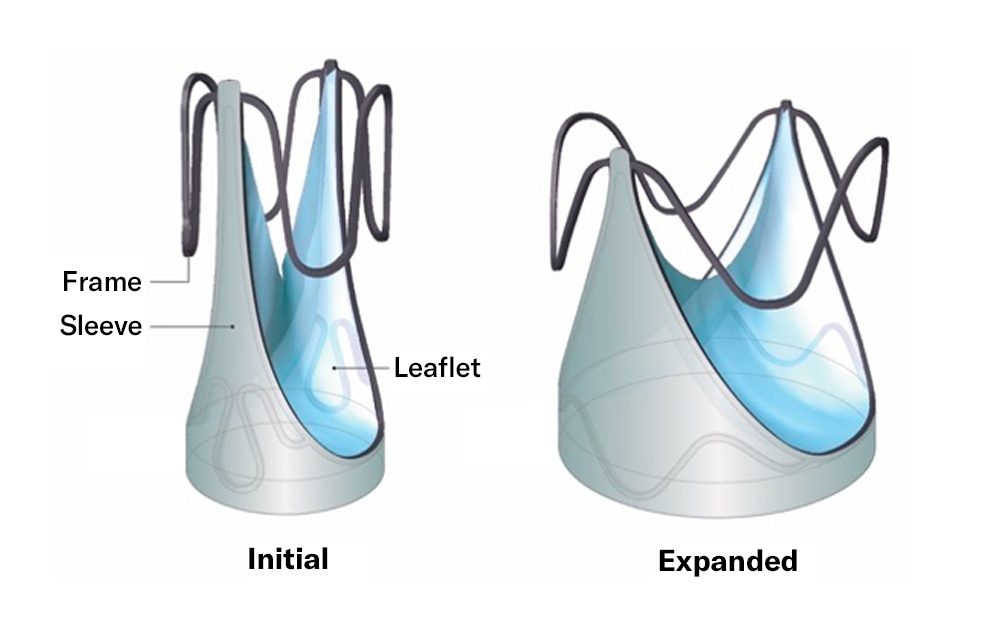

The Autus Valve is an artificial valve made of stainless steel, and its synthetic material has a long history of clinical use in children. It is implanted by open-heart surgery, and as the child grows, the valve can be expanded using a catheter. For the catheter procedure, a soft, hollow plastic tube is passed through a vein in the leg and up into the heart and lungs. The doctor then carefully positions a wire with a balloon inside the Autus Valve and inflates the balloon to expand the steel frame. Once it is at the desired size, the balloon is deflated and removed, leaving the valve in position but at a bigger size.

Image courtesy of Autus Valve Technologies, Inc.

“The beauty of this technology is we get to customize the valve before it’s sewn into place,” says Dr. Barry. “When the child starts to outgrow the valve, we do a same-day procedure with a catheter that takes a few hours, and it’s really the substitute for an open-heart surgery.”

Dr. Bacha successfully implanted the Autus Valve last January, making Yasin one of the first children in the country to have it. “He is leading the way for kids with congenital heart disease,” says Dr. Barry. “For anybody else who’s thought about this valve, I talk about an amazing 7-year-old who we met and did this for, for the first time. And that’s Yasin.”

Life as a ‘Superhero’

Because the technology is new and Yasin is young, it’s difficult to predict when he will need the valve expanded over the course of his teenage years and into adulthood (at which time the valve can be replaced). Dr. Thanjan and Dr. Barry will monitor Yasin closely with echocardiograms at least once a year.

“I think for all families who go through this, it’s never easy, but the most important thing is to have good doctors and hospitals,” says Adam. “I love superheroes, so I tell Yasin that he’s like Iron Man and they put something special inside of his heart. I always say it’s going to make you stronger, and you’re going to go through these journeys, and it’s part of you.”

Yasin is now like any other 8-year-old, playing video games and basketball in the backyard with his older brother, Mikhail. “It felt really nice when they put in the new valve,” he says. “No one could stop me from running. I had so much energy.”

Dr. Thanjan remembers a moment during the presentation when she called Yasin her “heart pioneer.” “I think he realized what he had gone through, and he was really proud of himself,” says Dr. Thanjan. “He said, ‘Wow, I really am a heart pioneer.’”