Amazing Things: Lauren Manning

Sixteen years after two planes struck the World Trade Center, a 9/11 survivor has a new outlook on life — and is thriving.

Lauren Manning is used to making split-second decisions under pressure. A former Wall Street executive, an athlete, and the daughter of a Marine, she says, “In a crisis, no matter who you are, you can surrender or put on your game face.”

That attitude didn’t desert her September 11, 2001, when she arrived at 1 World Trade Center and turned the corner into the lobby, toward the elevators, at 8:46 a.m.

She barely paused when she heard an ear-splitting sound, chalking it up to construction. In reality, the piercing whistling was exploding jet fuel coming down the elevator from American Airlines Flight 11. The jet had crashed into floors 93–99 and cut off escape routes from the floors above, including 101–105, where hundreds of Lauren’s Cantor Fitzgerald colleagues were at their desks. For an instant, the tower trembled, then fire exploded from the elevators, engulfing Lauren and scores of others on the south and west sides of the lobby.

As the flames enveloped her, igniting her back and arms, Lauren fled, making it across the six lanes of West Street traffic to a grass embankment, where she dropped and rolled with the aid of two good Samaritans.

“I was in complete and utter pain, I knew I needed a burn center, and some of the first words out of my mouth were, ‘Get me to Weill Cornell, now!’” she recalls yelling.

She wouldn’t arrive at NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center until 10 hours later. She was first admitted to another hospital, one without specialized burn care. That night, Lauren was transferred through the locked-down city to the William Randolph Hearst Burn Center at NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell.

What It Takes to Heal Burns

Seventeen other survivors were in the intensive care unit that night. Many wouldn’t make it. Lauren’s burns were catastrophic and covered 82.5 percent of her body.

In the weeks after, she faced severe infection and an onslaught of surgeries, including grafts, partial finger amputations and joint fusions.

“She also had serious injuries to her lungs, and we needed to put her on a ventilator,” says Dr. Palmer Bessey, associate director of the Hearst Burn Center and the Aronson Family Foundation Professor of Burn Surgery at Weill Cornell Medicine. Her chance of dying was estimated at 90–95 percent.

Her accomplishments every day, from the moment she opened her eyes, made grown people weep, and it kept happening again and again.

Greg Manning

The medical team, led by Dr. Roger Yurt, retired chief of burns, critical care, and trauma at the Hearst Burn Center and Professor Emeritus of Surgery at Weill Cornell Medicine, then the director at the burn center, would perform 11 surgeries. Each had multiple procedures, including using cadaver skin and skin grafts as Lauren lay in an induced coma for almost two months.

“The body eventually rejects the cadaver skin, so you have to keep shaving off what healthy skin she has left, expand and stretch it to cover a part of the burned area, then wait for the healthy areas to heal, and then take more skin to cover another small part of the burn,” says Dr. Bessey.

Surgery was only the first step.

“When they brought me out of the coma, it was already late October,” Lauren recalls. “I knew I’d been injured, but I still somehow believed that I’d be going home at the end of the week. I guess I had a positive attitude from the outset,” she said with a laugh.

Lauren would learn how seriously she’d been wounded when Dr. Yurt explained the extreme nature of her injury and that there was no certain release date.

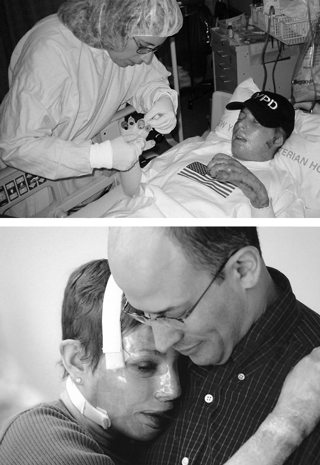

Lauren during her recovery.

Occupational and physical therapists continued to work on her limbs, as they’d begun doing weeks before she was brought out of the coma. On November 12, Lauren’s physical therapists announced that her goal that day was to walk to a chair in the corner of her room, about 4 feet from her bed.

“I thought, ‘These people think that’s all I can do? That’s easy — I’ve got this,’” Lauren recalls. Within minutes, she discovered she didn’t have the strength to sit up on her own. Putting weight on her feet and her grafted legs for the first time in two months was excruciating.

“It felt as if my body was pulling apart. I almost passed out from the pain.”

Yet with help, she dragged her legs and made it to that chair, tears streaming down her face.

“I was elated,” she says. “I called it the day of the walking mummy.”

Three days later, determined and flanked by PTs once again, she walked 30 feet to the ICU nurses’ station. Nurses, doctors, and therapists crowded around. One of the occupational therapists ran out to the corridor, its walls covered with cards from well-wishers around the world, to get Lauren’s parents, exclaiming, “Lauren is walking!”

“I felt an incredible surge of freedom,” Lauren says. “Everyone was clapping and crying, and I realized that my fight was their fight and that we were a team. My triumphs were ours together and that this was our victory.”

Part of Lauren’s motivation was her son, Tyler, 10 months old the day of the attacks, who was not allowed to see her until 67 days afterward, when the risk of infection was less severe. In the time they’d been apart, he had his first birthday and learned to walk. The day of the visit he toddled past, not recognizing her.

“I could see he was afraid and uncertain, so I sang as best I could, having just had the tracheal tube removed, a little lullaby that used to soothe him,” she says. At last he turned toward Lauren. “He smiled at me. Everything I had fought and hoped for was embodied in that moment of recognition. That visit, and the ones that came after, fueled me forward.”

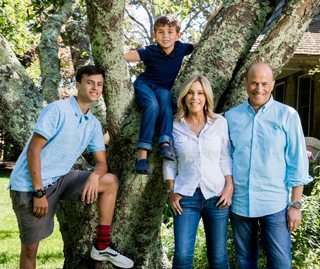

Lauren and her husband Greg, with sons Tyler, 16, and Jagger, 7.

“Her accomplishments every day, from the moment she opened her eyes, made grown people weep, and it kept happening again and again,” says her husband, Greg, whose best-selling book, Love, Greg & Lauren, recounts the first six months of Lauren’s recovery. “She’s the strongest person I know. She said she wanted to make the injured woman disappear, and like every other impossible goal she set, she achieved it.”

Lauren credits her equally determined medical team.

“It was the power and hope in everyone’s heart on a day-to-day basis, caregivers’ footsteps outside my door in the quietest hours of the night, checking on me,” Lauren says. “Every single person there had the same goal: to win. We met every setback with the desire to conquer the next. I existed outside the bell curve of survival odds, but together we accomplished things that no one believed I could.”

A Delicate Balance

Helping burn survivors requires being “tough but supportive,” says Dr. Bessey.

Lauren agrees. “It’s sometimes not clear to clinicians to know how far to push someone — to know when the patient has reached their breaking point,” she says. Yet despite that push-pull, “I remained relentless, and amidst all the pain we also managed to laugh through the tears.”

After 91 days, Lauren was discharged to a rehabilitation hospital for three months.

“I’d been asking about leaving for so long, but as the day approached, although I was initially ecstatic, I was also afraid,” she admits. “I knew the people in the hospital, the routine — it had become my home.”

Lauren went home in March 2002. She was beginning the next phase of a decade-long recovery. She traveled to NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell five days a week for hours of grueling occupational and physical therapy. On Sundays, an occupational therapist she befriended at the hospital came to her home for another session.

“My relationship with the hospital and my caregivers lasted for years. I had frequent operations, on average every nine weeks during the first few years, to help release scar tissue on my hands, my arms, my shoulders, and back. I was there all the time. NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell became my workplace, my recovery, my full-time job.”

On the 10-year anniversary of the terror attacks, Lauren’s best-selling memoir, Unmeasured Strength: A Story of Survival and Transformation, published. Since then, Lauren has shared her story of inspiration and courage as a speaker to audiences throughout the U.S.

I felt an incredible surge of freedom. Everyone was clapping and crying, and I realized that my fight was their fight and that we were a team. My triumphs were ours together and that this was our victory.

Lauren Manning

“She is the reason for her success,” says Dr. Bessey. “We were able to keep her body alive, but she was the one to get her life back.”

One of Lauren’s prime motivations is mothering her two sons, Tyler, now 16, and Jagger, 7, born in 2009 with the help of a gestational carrier. “I fought so hard to get back to being a mom,” she says. “When I look into my sons’ eyes, it’s all there — everything I fought for, the grace I feel for just being alive.”

These days, Lauren is making the most of that, as co-founder of a consumer privacy startup, YouBoard Inc., and she is working on a master’s degree in narrative medicine/bioethics at Columbia University.

“Before the attacks, I used to breeze right by the little things, all those expected or mundane activities that you don’t pay attention to, like seeing a friend for lunch or bringing your son to school. I treasure each of these simple and joyful moments now,” she says.

The 658 of her colleagues who were killed on 9/11 are never far from her thoughts, particularly every September 11, when she gathers with her Cantor Fitzgerald family for their annual memorial.

“I worked alongside those people for years. So many were good friends,” she says. “I was half a step removed from the ones who died. But they didn’t have the chance I had to fight. I have never failed to appreciate that gift.”

She also makes time to see her former medical team. “It’s like returning for a school reunion — we recount the old stories,” she says. Of course, it’s much more than that. “I should be dead, but I’m not, and that’s not because of luck, but because of the fortitude, talent, and commitment we had as a team. We were in it together, and not one of us wanted to lose.”

As Lauren says, “Every day you have a choice. We chose to make it count.”