After Beating Sickle Cell Disease, This College Student Has Big Plans for the Future

Francisca Kwakye left Ghana as a young child to receive life-changing treatment for sickle cell disease. Now cured, her dream is to improve health care access for others.

In her off-campus apartment, University of Pennsylvania junior Francisca Kwakye is reading over new course materials and filling out her daily planner.

Her schedule is packed, and it’s not hard to see why. The Health and Societies major has a concentration in Health Policy and Law and a double minor in Political and Cognitive Science. She is on the boards of multiple school clubs and works as a teacher’s assistant in a Twi class, a native language of Ghana. Through it all, she still finds time to run on the treadmill and enjoy college life with her best friend and roommate.

Francisca’s ambition and her achievements are impressive, but her personal journey is what makes her inspiring. Diagnosed with sickle cell disease as a young girl in Ghana, she spent much of her childhood in chronic and crippling pain, which eventually brought her to the U.S. to seek treatment and ultimately receive a bone marrow transplant at NewYork-Presbyterian Morgan Stanley Children’s Hospital. “Because of the care I received at NewYork-Presbyterian, I am achieving my dreams,” says Francisca. “If you asked the 8-year-old me if I would go to an Ivy League school, I wouldn’t have believed it. You never know what the future holds. But going through sickle cell at an early age inspired me to help others who need care.”

After her sickle cell disease diagnosis, Francisca moved from Ghana to New York City with her two older sisters to seek better care.

An Elusive Diagnosis

Francisca was born in Konongo, Ghana, in 2003, and lived with her mom and two older sisters. Her father had relocated to New York City for work when she was an infant, but her grandfather would help her with homework and feed her dinner when he came home from teaching at a university.

While Francisca had many happy moments growing up, she experienced many ups and downs because she was often in pain. “I had excruciating pain that was completely unpredictable, and my eyes were yellow,” says Francisca. “Sometimes my sister would carry me on her back to school because I couldn’t walk.”

For years, Francisca was misdiagnosed with typhoid fever by doctors at her local hospital. They would send her home with pain medication, only for her to return weeks later. In 2012, she finally visited a specialized hospital where she got a blood test for sickle cell disease, a group of genetic blood disorders.

Healthy red blood cells are normally shaped like doughnuts, but in sickle cell disease, the cells have a sickle-like shape. Because of the abnormal shape, the cells get stuck in small blood vessels and block the flow of oxygen and blood throughout the body, causing pain and exhaustion and putting people at high risk for strokes and organ damage. Sickle cell disease affects about 100,000 people in the U.S. and 20 million people worldwide, and disproportionately impacts people of African descent and other communities of color.

After her diagnosis, Francisca and her sisters joined her father in New York City to seek better care for Francisca. “It was kind of sad for me to leave my mom, but I had my sisters,” says Francisca. “We had to learn a new language, make new friends, and assimilate.”

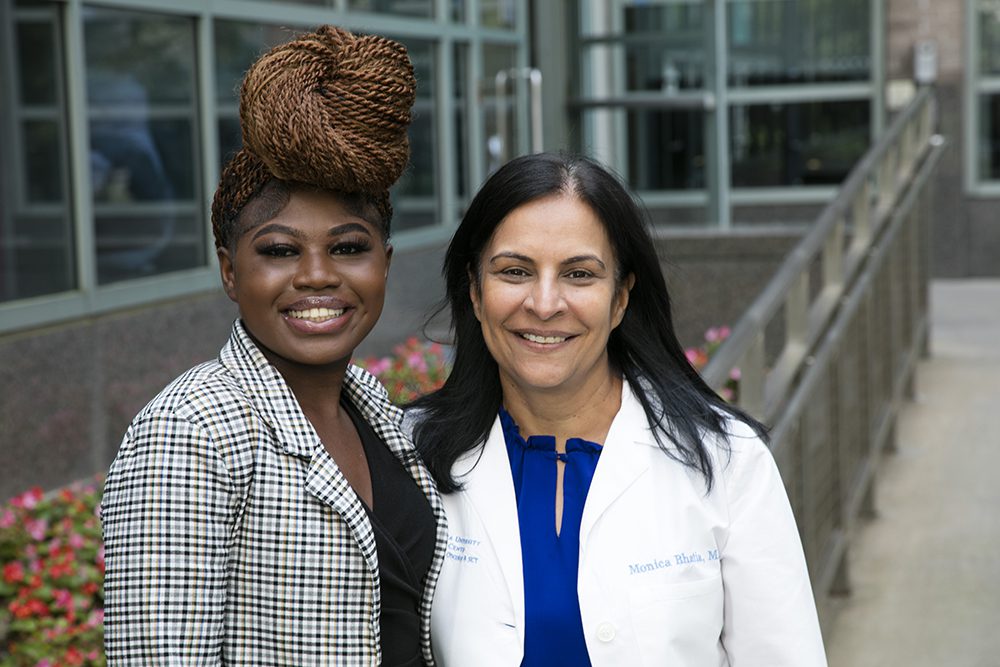

Pediatric Hematologist and Oncologist Dr. Monica Bhatia (right) performed Francisca’s bone marrow transplant and cured her of sickle cell disease.

Finding Hope With the Help of Family

Francisca went to a local clinic in the Bronx and started taking medications for her sickle cell disease. The options for treatment are different for everyone, but most patients are given medicines and blood transfusions to reduce pain and add normal blood cells. A cure is possible with a bone marrow transplant, but the approach is risky and requires a donor who is a full match — ideally, a sibling. Only 15% of patients with sickle cell disease have a sibling who can be a donor, and if there is a match, cure rates are about 90% to 95%.

Because she had sisters with normal blood cells, Francisca’s hematologist at the clinic felt a bone marrow transplant could be possible. He referred her to Dr. Monica Bhatia, director of the Pediatric Stem Cell Transplant Program at NewYork-Presbyterian Morgan Stanley Children’s Hospital. The pediatric program is one the largest in the country for sickle cell disease bone marrow transplants.

“I remember Francie coming to see me with her older sister and dad, and what struck me was that she was so motivated and gifted,” says Dr. Bhatia. “As pediatricians, we advocate for transplants as early as possible if there is a donor because sickle cell disease only gets worse with time — but it’s a family decision, and there are sacrifices. Francie took it to heart. She said, ‘I want to live my life just like anybody else.’”

The transplant process began with a series of blood tests to confirm that Francisca’s older sister, Esther, was a match. Dr. Bhatia and a nurse practitioner, Ria Hawks, met with Francisca, Esther, her father and mother, who moved from Ghana by then, to educate them about every step. And when Francisca needed an MRI to check for complications, a child-life specialist always stayed by her side to comfort her through a sometimes-scary process.

Francisca also had to undergo chemotherapy for eight days to destroy the unhealthy blood cells in her body and prepare her bone marrow for Esther’s healthy stem cells. “The first time I cried was when they had to shave my hair because of the chemotherapy,” she says. “But they understood that I was a child going through this and my emotions were all over the place. Everyone is super nice. They are like my family.”

On October 22, 2014, Francisca received Esther’s healthy stem cells. The transplant was a success, and after six weeks of monitoring to make sure her body did not reject the new cells, Francisca was discharged. “I have patients who after a transplant don’t really know what to do with the extra time they have outside of the hospital and not being in pain,” says Dr. Bhatia. “Francie embraced it, and now the sky’s the limit.”

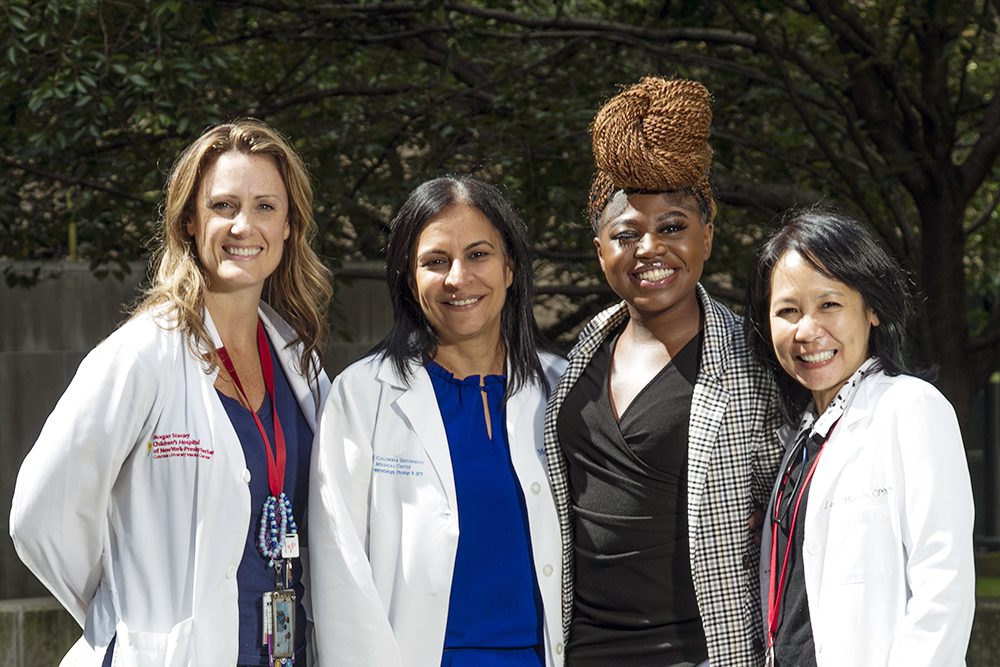

Left to right: Nurse practitioner Kelly Vitale, Dr. Bhatia, Francisca, and nurse practitioner Leah Violago reunited at NewYork-Presbyterian Morgan Stanley Children’s Hospital nearly nine years after Francisca’s transplant.

Free to Pursue Her Dreams

When Francisca came home, her fight to overcome sickle cell was not over. At just 12 years old, with the help of a social worker on her care team, she became responsible for keeping track of her medications and follow-up appointments and was home-schooled three days a week to complete sixth grade because she was still immunocompromised. “There were times when I felt like, is the transplant worth it? Did this even work? I had to go through pain, lose my hair, and I gained weight from the medicine,” she says. “But going through sickle cell at a young age made me resilient.”

Francisca’s life steadily went back to normal when she entered the seventh grade. She also stayed in touch with members of her former care team, especially Hawks, with whom she’d formed a close bond while in the hospital. “Ria has always been so supportive of me,” says Francisca. “We still speak all of the time. She called me yesterday to ask about what classes I’m taking.”

Her ambition grew as she entered high school, where she co-founded the Black Student Union and joined the African dance team. As a member of the social justice club, she traveled to Washington, D.C., to meet with staff members of U.S. Sen. Chuck Schumer of New York to talk about immigration reform and climate change. By this time, Francisca no longer needed medications and only needed annual checkups. “If I could sum it up with one word, I would say I felt liberated,” she says. “Without Dr. Bhatia, my transplant, or access to the amazing care at NewYork-Presbyterian, I wouldn’t have had these opportunities.”

While Francisca is embracing her new life at Penn disease-free, sickle cell disease will always be a part of her identity. This summer, she was awarded a Voyager Scholarship, a public service scholarship co-created by the Obama Foundation to help future leaders pursue a summer work-travel experience. “I’m excited to go to a different country and learn about how health policies affect the patients there,” she says. “I think it will be insightful.”

After college, she plans to go to law school and use her degree to help low-income patients with blood disorders get access to quality health care and medications. “I can’t imagine myself in a different career, because I know how it feels to be in a place of vulnerability,” she says. “Sickle cell disease is like a shadow. It will always follow me and be something I look back on to remember my purpose in life.”