A Teenage Girl Finds Her Smile After a Series of Reconstructive Surgeries

Born with a condition that stunted the growth of her face, Jade Metivier and her family turned to NewYork-Presbyterian for the complex surgical treatment she needed to breathe, speak and smile properly.

Christi and Mark Metivier vividly remember their first meeting with Dr. Thomas Imahiyerobo, director of cleft and craniofacial surgery at NewYork-Presbyterian, in his office at the NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving Medical Center. It was May 2023, and the plastic surgeon showed them a series of scans and visualizations on his laptop that outlined his plan for reconstructing their daughter Jade’s facial bones. Jade, who was 13 at the time, had a condition known as midface hypoplasia, in which the bones around the eyes, cheekbones, and jaw don’t grow at the same rate as the rest of her face. As a result, it was difficult for her to eat, speak, and even smile.

While they were hopeful, the extent of the reconstruction was a lot to take in. It would require a series of surgeries in which Dr. Imahiyerobo would separate her facial bones from her skull and move them slowly forward using mechanical devices.

“It kind of knocks the wind out of your sails,” says Christi. “It’s a lot to digest. But Dr. Imahiyerobo and the team gave us the confidence and the reassurance that we weren’t going through this alone.”

Jade, on the other hand, was fearless. “You can imagine that if you walked into a room and said, ‘I’m going to separate your face from your skull,’ not a lot of people would sign up for that,” says Dr. Imahiyerobo, who is also the section chief for pediatric plastic surgery at NewYork-Presbyterian Morgan Stanley Children’s Hospital of Children’s Hospital of New York. “Jade never missed a beat. She said, ‘Let’s go. I’m ready.’”

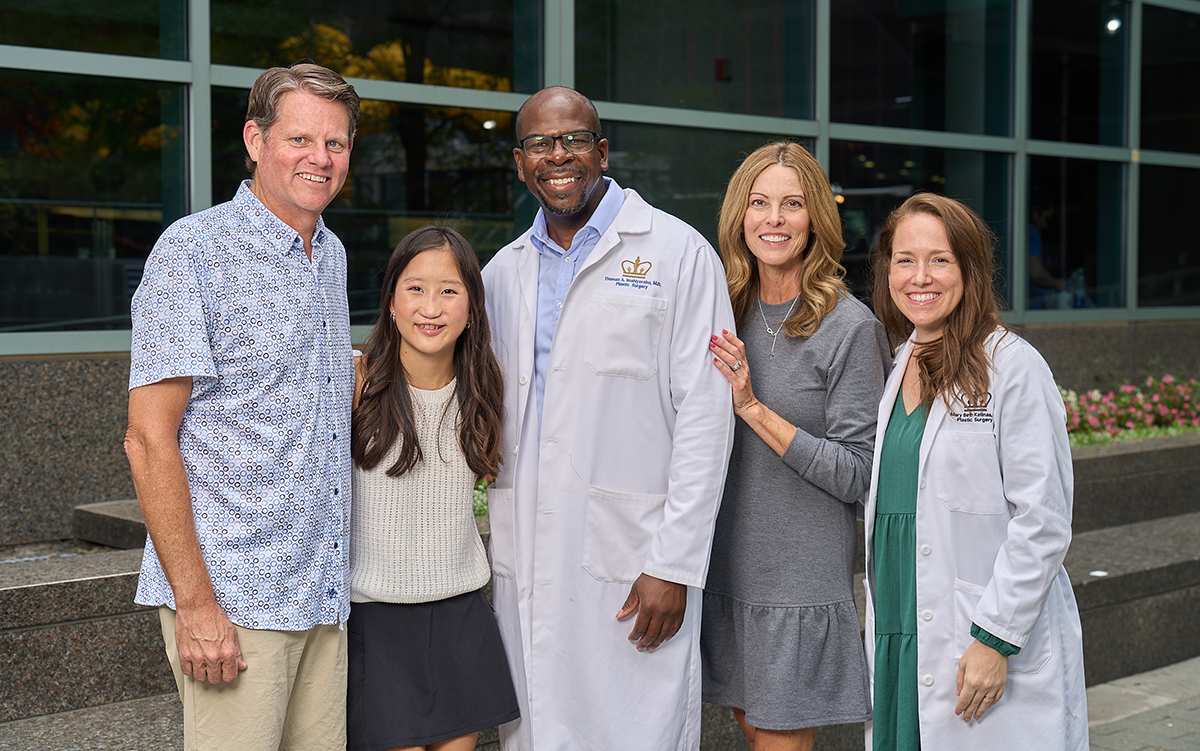

Dr. Imahiyerobo and nurse practitioner Mary Beth Katinas (far right).

Finding the Right Care

The medical condition Jade was confronting had been with her since she was a young girl, but the signs of it manifested as she grew. Jade was born with a cleft lip and cleft palate, a birth defect that occurs when a baby’s lip or mouth does not form properly. The abnormality can cause problems with feeding and speech, so when Christi and Mark adopted Jade from China at 2 years old, they had her lip and palate surgically repaired right away.

But as Jade entered puberty at age 11, they noticed the bones in the middle of her face weren’t growing as fast as her forehead and chin, and it was affecting her everyday life. “I couldn’t bite into my food, and it was harder to talk and harder to smile,” Jade says.

“We did a lot of research to find who could handle her case,” says Mark. “We decided to meet with Dr. Imahiyerobo, and what struck me was his compassion and his attention to detail. We knew we’d come to the right place.”

That’s when the Metiviers, who live in the Kansas City metropolitan area, knew they would have to find a hospital that could handle her complex care. Conditions like Jade’s are rare, occurring in about one in 10,000 live births, and NewYork-Presbyterian is among only a handful of academic medical centers in the country that have the expertise to treat it.

For craniofacial cases like Jade, Dr. Imahiyerobo works in tandem with Dr. Caitlin Hoffman, a pediatric neurosurgeon at NewYork-Presbyterian Komansky Children’s Hospital of Children’s Hospital of NewYork and the director of craniofacial surgery in Neurosurgery at NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center. This collaborative approach brings together experts from Columbia and Weill Cornell Medicine.

“Within our program, we give our patients access to multiple specialists across many different disciplines and provide care plans that address both the medical side and their functional needs,” says Dr. Imahiyerobo.

A Complex — and Virtual — Surgical Plan

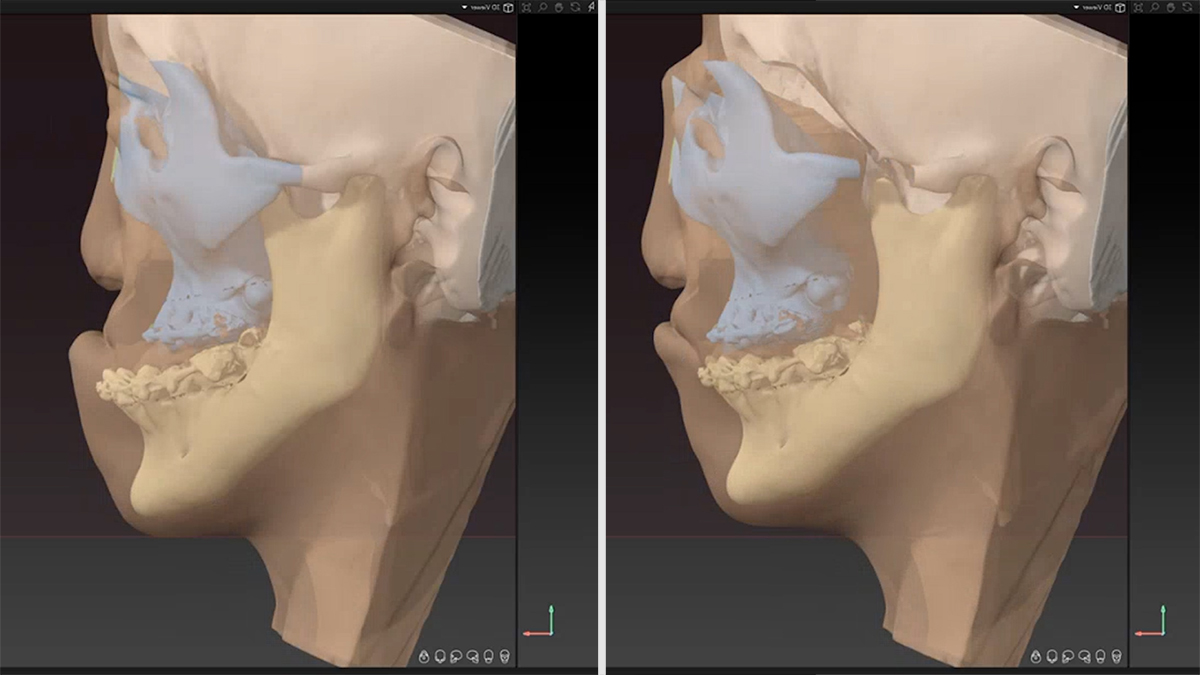

In Jade’s case, her lower jawbone and eye sockets extended forward, while her nasal bone was flat and her upper jaw pushed back, which obstructed Jade’s airway and prevented her from being able to put her lips together.

But what made Jade’s case particularly complex was that she lacked bone structure around the nasal, orbital, and jaw area, and her cleft lip and palate affected the soft tissues of her face. “I was really worried about how her soft tissues would respond,” says Dr. Imahiyerobo. “Would her lip be able to move into the normal position? Would we be able to get enough structure under her nose? How would we be able to work around her eyes and get them to sit back into her head?”

The team’s treatment plan included a craniofacial disjunction surgery, where Dr. Imahiyerobo and Dr. Hoffman would cut the midfacial bones, separate them from the skull, and move them forward. In doing so, all the organs — the eyes, nose, teeth, and mouth — would become aligned.

Then, they would lengthen Jade’s bones into place over time, a procedure called a distraction osteogenesis. It would require surgery to attach two small, metal devices, called distractors, on either side of Jade’s skull, underneath her skin. The distractors have cranks, gears, and a rod attached to them that run to the outside of Jade’s head. For three weeks, Christi and Mark would have to turn the distractors with the rod about one millimeter a day to gradually move her bones forward. Once the bones were in the right position and healed, the distractors would be removed via surgery about three months later.

Before the first operation, Dr. Imahiyerobo and Dr. Hoffman created a virtual surgery plan, a cutting-edge innovation that allows surgeons to perform the surgery in a virtual world, from start to finish, using CT scans and a 3D model. A craniofacial disjunction usually takes about 12 hours, but with virtual surgery planning, they successfully completed Jade’s in about half the time.

“It’s like taking NASA-level simulation into the operating room,” he says. “It provides a measure of safety, it increases the efficiency, and it really maximizes the success of the surgery.”

Finding Her Confidence After a Long Recovery

While Jade was in the pediatric intensive care unit recovering, she had to stay sedated and have her eyes sewn shut because of the swelling in her face and airway. The care team knew she was a dancer and huge Taylor Swift fan, so to make her feel more comfortable during recovery, they played Jade’s favorite song, “Blank Space.”

“Lo and behold, Jade started to move her hands to the rhythm while she was still intubated and sedated,” says Dr. Imahiyerobo. “It was remarkable. At that moment, I knew this kid was going to be OK.”

Between the craniofacial disjunction surgery, distractor removal, and an extensive surgery to reconstruct Jade’s nose, chin and jaw, the Metiviers spent almost 50 days in New York City, where she not only had her surgeries but also had physical therapy, dental care, orthodontic treatment, neurosurgical assessments and a speech evaluation. Throughout her treatment, Jade’s spirits stayed high — she was even able to catch a Broadway show at one point, wearing a hat that covered her distractors. “What helped me through the process was the support from my family and friends,” says Jade. “I focused on what I wanted to do after the surgery instead of the pain I was having.”

Although her journey was a long one, “our goal with craniofacial surgeries is always to elevate someone’s quality of life while also making them feel more like themselves,” Dr. Imahiyerobo adds.

For Jade, that’s exactly what happened. Now a freshman in high school, she spends her time with friends, watching Kansas City Chiefs football games, and doing what she loves most: dancing. She does tap, ballet, acrobatics, jazz, and contemporary, and this winter, she is performing in a ballet show and a hip-hop dance competition. “The surgeries gave me more confidence in my dance,” she says. “When you perform, you have to smile, and I like the smile I have now.”

Additional Resources

- The Craniofacial Center at Children’s Hospital of New York at NewYork-Presbyterian features renowned pediatric surgeons and specialists, including ENT, speech and swallow therapists, pediatric dentists, orthodontists, pulmonologists, and pediatric child life specialists. The Center offers minimally invasive approaches to craniosynostosis and cutting-edge technology, including virtual surgical planning using 3D imaging. Learn more about the Craniofacial Center.