With a New Heart, a Tennis Player Feels Like a ‘True Champion’

Though he was born with a heart defect, Mati Luik didn’t let that stop him from living an active lifestyle until he collapsed on the court one day. In 2023, he became the first patient to receive a heart transplant at NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center.

Mati Luik was playing in his winter league tennis match in December 2019, when he felt his heart racing. He quickly lay down to avoid falling since he had collapsed on the court a year before and had to be hospitalized.

In that moment, Mati admits, he knew it was only a matter of time before he would need to consider a heart transplant. Born with a heart defect, Mati had managed to live an active lifestyle, playing tennis competitively for much of his life. But it was becoming clear that his heart was failing him.

“Things were changing and deteriorating in a way that I definitely wasn’t prepared for,” says Mati.

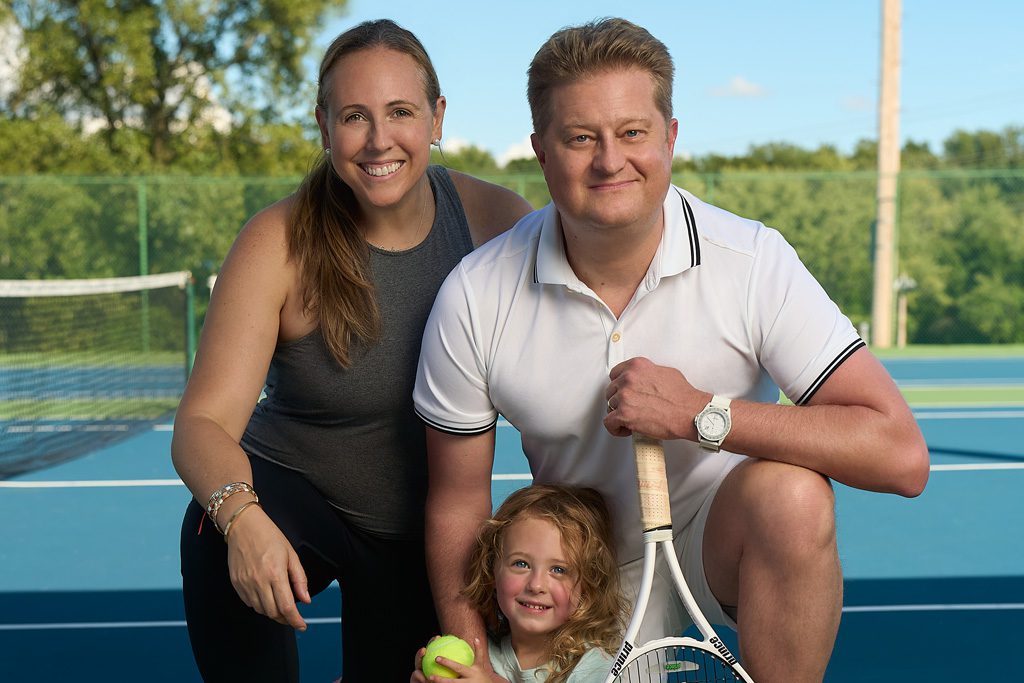

Soon after, Mati reluctantly called his tennis game quits, which became easier in 2020 when his daughter, Carolina, was born and he and his wife, Veronica, hunkered down like everyone else during the early days of COVID-19. But in 2022, after a routine battery of tests showed some frightening numbers, two of his doctors, Dr. Harsimran Sachdeva Singh, director of adult congenital heart disease at NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center, and Dr. Maria Karas, medical director of the cardiac intensive care unit, told Mati that it was time to get things in motion for a transplant.

Mati Luik with his wife, Veronica, and daughter, Carolina.

Finally, what Mati knew would happen one day was happening now. But he didn’t know that the hospital where he had been a patient for most of his life was expanding its renowned heart transplant program to its NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center campus — previously, the heart transplant program was only based at its NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving Medical Center campus. In just a matter of months, he would become its first heart transplant recipient.

“I was thrilled to be patient number one,” Mati recalls of his surgery, which was performed on February 1. “I had a lot of experience with Dr. Singh, Dr. Karas and all their nurse practitioners, so I was confident these are some of the best people in the world and I was in good hands.”

A Lifetime of Heart Care

Mati, now 43, was born with congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries (CCTGA), a congenital heart defect where the heart’s ventricles and main arteries are reversed, forcing the stronger left ventricle to pump blood to the lungs and the weaker right ventricle to take on the harder job of pumping blood to the entire body.

“It’s like a car engine being pushed consistently beyond its capacity,” explains Dr. Singh, who is also the David S. Blumenthal Assistant Professor of Medicine at Weill Cornell Medicine. “Over the years, CCTGA can lead the right ventricle to fail, because it is pushing against the much higher pressures of the rest of the body as opposed to the lower pressure of the lungs.”

The CCTGA was diagnosed when Mati was a baby and, one day, his mother found him very blue. At 2 1/2, he had his first surgery at NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving Medical Center to promote blood flow. The procedure went well and enabled Mati to enjoy what he says was a “typical childhood,” filled with sports that fostered a love of tennis, which he discovered at age 10.

“I was never afraid to try anything new or push myself,” Mati says. “Honestly, [my illness] was never in the back of my mind at all.”

Between different corrective surgeries, he was able to enjoy a decent quality of life, but he knew that additional surgeries were in his future, and he’d need to be followed closely by cardiology experts, so after college he started seeing Dr. Singh. When he was in his early 30s, Mati’s health started to decline.

It’s hard to describe the feeling, going from such a damaged heart to a new, properly functioning heart.

Mati Luik

“That’s the reason Dr. Singh sent him to me,” Dr. Karas recalls, “Even though he didn’t need [a transplant] then, we told him we thought that he was going to need it at some point in his lifetime.”

In 2015, Mati received a heart valve replacement, followed by a pacemaker/defibrillator in 2016 to help keep his heart rhythm regular. The interventions got him feeling better and he was able to resume his active life. He was able to hike with Veronica in Patagonia and play regularly in tennis leagues. It wasn’t until his fainting spells that Mati’s doctors started to plan for the next step in his heart journey.

“Heart failure can take many different paths,” says Dr. Karas, who is also an assistant professor of medicine at Weill Cornell Medicine. “The scary part is that arrhythmias can be very unpredictable, and it’s hard to know when they’re going to hit.”

“Number One” Heart Transplant Patient

By 2022, Mati would ping-pong from feeling great to feeling ill again, so that fall, Dr. Yoshifumi Naka, surgical director of heart failure, cardiac transplantation and mechanical circulatory support programs, was brought onto the team. With his condition worsening, Mati went on medical leave from work and, on November 3, was listed for a donor heart, and the wait began.

Around the holidays, Mati learned he needed to be put on an intravenous heart failure medication called milrinone, and he’d need to be put on a pump to administer it continuously. On New Year’s Eve, the nurses served celebratory sparkling cider, and then Mati went home — attached to the pump — to continue to wait for the call for a new heart. Finally, on the last day of January, he got the news that a heart was available. Relieved and excited, Mati went into his long-awaited surgery the next day.

“Knowing the team so well and being a part of it for so long just made things a lot more comfortable,” he recalls. “It was just relief. It was like, ‘All right, finally! This is finally happening… Let’s go!’”

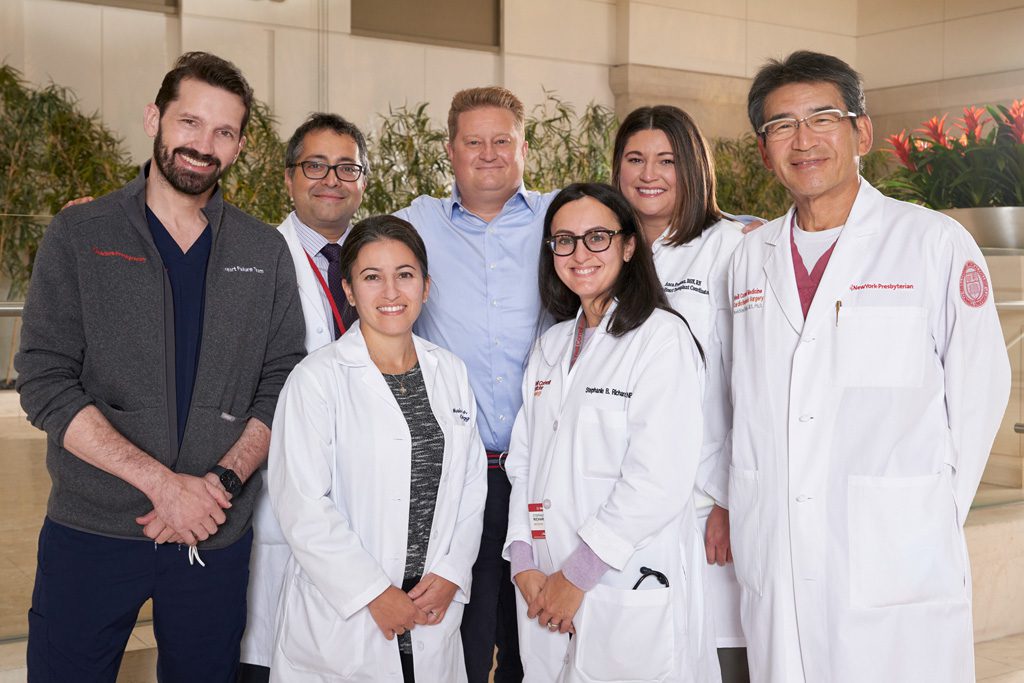

The surgical team working on Mati’s heart transplant.

Mati says he felt confident that he was getting a team of leading experts, who would work through any complexities his case presented. For example, when Dr. Naka started the operation, he saw that, due to previous repair work, Mati had little pericardium, the membrane surrounding the heart, which made it difficult to “explant the heart.”

“Usually, I spend about two hours from the skin incision to take the heart out,” Dr. Naka says. In Mati’s case, the surgery took over three hours, but was successful, and Mati was soon in recovery. He had been told that he wasn’t going to be able to get up and walk the next day, but Mati had other plans.

“He said he decided that morning that he was going to get up and walk,” recalls Dr. Naka, who is also the Stephen and Suzanne Weiss Professor in Cardiothoracic Surgery (I) and a professor of cardiothoracic surgery at Weill Cornell Medicine. “I think I slept in my office because [surgery] went to midnight or so… And then, the next day, early in the morning, I went to the ICU and Mati was doing fine.”

When Dr. Naka went back to the ICU later that day, he couldn’t believe what he saw.

“I was so surprised that he was walking,” Dr. Naka says, admitting he may have shed a tear. “I’ve never seen this, because transplant patients don’t walk the next day.”

“It’s hard to describe the feeling,” Mati says, “going from such a damaged heart to a new, properly functioning heart.”

To the surprise of his care team, Mati was able to walk the day following his heart transplant.

A Chance to Help More Patients

NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving Medical Center has long been a leader in heart transplant. Expanding the program to NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center now means that patients can get access to heart failure services throughout the region — and perhaps closer to home — throughout their lives.

“The relationship between congenital heart disease doctors and congenital heart patients can be a very special and meaningful one, because of its longevity,” says Dr. Singh. “Most of these patients end up needing care when they’re children, and as adults, they will develop adult-specific problems that require additional interventions. So, it becomes a lifelong commitment.”

“It was a long process, and it was really in some ways a beautiful process,” says Dr. David Majure, medical director of the Heart Transplant Service, of building the new program that led to Mati’s transplant. “Because every level of the hospital became heavily involved in making sure that it was successful…. We had representatives from the intensive care units, from the post-surgical intensive care units, from anesthesia, from administration, from the outpatient care… The nursing involvement really was quite phenomenal. Just the amount of people that wanted to make sure they got this right was very impressive.”

Mati with members of his care team.

Dr. Majure aims to create the best outcome for every patient. “I will not be happy or satisfied until I see the best long-term outcomes that we can possibly generate,” says Dr. Majure, who is also an assistant professor of medicine at Weill Cornell Medicine.

As for Mati, Dr. Majure says, “My job is to keep him healthy for years to come, so that he has the longest and best quality of life that he possibly can have.”

“It’s a new heart,” Mati says, echoing Dr. Majure’s sentiments on longevity, “but me being an athlete, I understand you still need to work out and build everything else up… That’s one of the big things that sports and tennis have taught me. If you believe it, if you work at something, you can just be better and do better.”

Mati is grateful for his care, and how the entire team got to know him as a person and listened to him, down to those who provided his meals while he was in the ICU and remembered what food he liked. He recalls the moment he was leaving the hospital: “They literally rolled out the red carpet for me. It was so meaningful to see all the people who played a role in bringing me to this moment.”

“It’s in those moments when you struggle that really define who you are and whether you’ll be able to reach the top and be a true champion. I’m looking forward to being able to watch my daughter grow up, and I’m ready to be the champion they know I can be.”

Additional Resources

Learn more about heart transplant services at NewYork-Presbyterian.