What to Expect in an Epilepsy Monitoring Unit

A neurologist explains what happens in an epilepsy monitoring unit and what to know if you need to stay in one.

Approximately 3.4 million people in the U.S. live with epilepsy, a common neurological condition that causes a disruption in the brain’s electrical network, sending irregular signals to the body that result in a seizure. The condition can usually be treated successfully with medication or surgery.

As part of the process of either diagnosing epilepsy, adjusting medications to treat it, or determining if someone is a candidate for epilepsy surgery, patients will often need to stay in an epilepsy monitoring unit (EMU). This is a facility where clinicians can safely observe a person’s seizures and monitor their brain activity to understand not only how often seizures are happening, but also where in the brain the electrical network is being disrupted.

To learn more about what to expect if you or a loved one need to spend time in an EMU, Health Matters spoke to Dr. Padmaja Kandula, a neurologist at NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center and director of the Comprehensive Epilepsy Center at Weill Cornell Medicine.

Dr. Padmaja Kandula

Why would someone need to spend time in an epilepsy monitoring unit?

Dr. Kandula: There are several reasons. One would be if a doctor is not sure whether a patient is having seizures due to a neurological issue or is experiencing something else, such as feeling faint because of a cardiac issue like cardiac arrhythmia. Clinicians would need to capture the event on video, with both electroencephalogram recordings (EEG), where electrodes are pasted to the head, and cardiac monitoring.

Other times there are patients with epilepsy who need medication adjustments. In an EMU we can make one or two medication adjustments under guidance, which is much safer and quicker than in an outpatient setting because adjusting epilepsy medications can lead to seizures.

Some patients might have seizures that are not easily visibly detectable, such as an absence seizure, where a person might stare off for a period of time. We would monitor for that or, if they already have a diagnosis, monitor how many seizures a person is having and for how long. This is particularly important for adults who live by themselves.

Lastly, there are people who don’t respond to medication treatment. If they have failed drug therapy, meaning they don’t respond to two or more different medications, they may come in to be monitored to see if they are candidates for epilepsy surgery.

How do you capture someone’s seizure in an EMU?

We will, within reason, try to safely trigger a seizure so we can capture the information we need to make the best clinical decisions for the patient. This is why these tests need to be done in a hospital setting, under the guidance and care of epilepsy doctors and nurses.

The easiest way to induce a seizure is to slowly lower a patient’s medication. We gently wean them off, and for most people, once the medication levels are low, they will have a seizure. We won’t lower them so much so that it puts them in any risk or they have back-to-back seizures, but we do need to capture a seizure event. Often things like sleep deprivation and flashing lights will trigger a seizure, so we will safely find ways to induce a seizure that we can closely monitor and observe.

There is no standard number of seizures we need to capture, but typically we want to reproduce the seizure event once or twice. We want to make sure we capture the usual event they have at home. Sometimes they may have more than one seizure and different seizure types, and we want to capture all of that.

How do you monitor a seizure while it is happening?

Technicians check the electrodes for EEG readings quite frequently to make sure the person is comfortable, and there’s a head wrap to make sure the electrodes stay on. There’s also concurrent cardiac monitoring because some seizures are accompanied by an exaggerated heart rate response. That could be the first sign somebody is in the middle of a seizure or starting a seizure. It’s also helpful in trying to differentiate between cardiac versus neurologic causes of loss of consciousness.

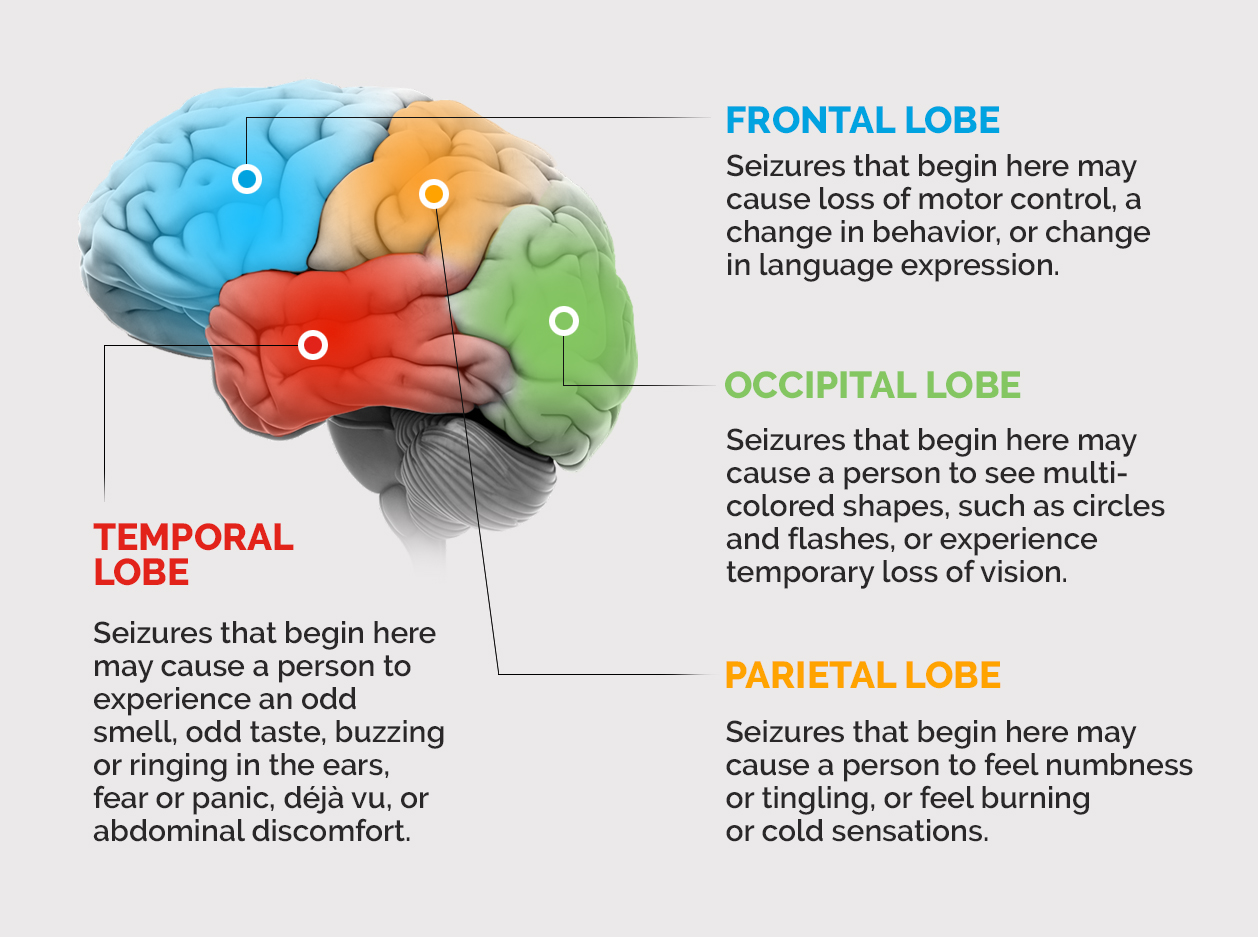

Sometimes when people have a large convulsion, their oxygen count drops temporarily, so we monitor that by having the patient wear a pulse oximeter on their finger. We also have two cameras in each room to give us a 360-degree view. Looking at the video helps us figure out how long a seizure is happening. Seeing the signs and symptoms of a seizure can also help us localize where it’s coming from in the brain, particularly if they need to have epilepsy surgery.

A person will experience different symptoms depending on where a seizure starts in their brain.

How long does a person need to stay in an EMU?

The average length of stay for an adult is usually three to five days. If we’re adjusting medications, it may be a shorter stay. If we’re documenting seizures for potential epilepsy surgery, it may be a longer stay. Patients will have to stay overnight to make sure we don’t miss an event. For children, it will also depend on how well they tolerate the monitoring. We can have patients as young as 2 years old, and their stays will be much shorter than adult patients because they may not be able to tolerate the testing needed over many days.

If a patient needs someone to stay with them, we encourage that, whether that’s a partner or spouse, a caregiver for an adult, or parents who want to stay with a child. In the EMU at NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center, there are private rooms with pull-away beds, room for more than one family member, and things like a refrigerator and television. These can also act as accommodations for people who don’t live nearby.

Does someone need to stay in an EMU to be diagnosed with epilepsy?

No. Some people can be diagnosed without going to the monitoring unit. If the clinical history matches a baseline EEG that shows the appropriate abnormalities, that’s enough to make an epilepsy diagnosis. At that point we could go ahead and start them on medication.

What happens when a person leaves the EMU?

Every day, the patient and any family or caregivers get a synopsis of what happened that day. This means that by the time they leave the unit, they have an entire diagnosis. The summary of the entire video and EEG recording is also available to them or their referring physician.

Additionally, when the patient comes in for a follow-up visit, usually within two weeks of discharge, we will already have their plan for treatment. For instance, if we started a new medication while the patient was in the EMU, that would be indicated in the discharge summary.

Why does a patient need to stay in an EMU to be monitored? Why can’t it be done remotely?

It’s best to do this in an EMU. These are specialized units so the staff, from the doctors to the nurses to the EEG techs, have advanced training in epilepsy. It wouldn’t be safe to lower someone’s medication to induce a seizure without clinical supervision, and you need someone with the right experience to respond if there’s an acute problem, like if someone has a severe seizure. Outside the EMU, we also wouldn’t be able to guarantee that someone could monitor the patient on video, and if someone knocks the electrodes off their head — which can happen if patients move around a lot — there’s no one to fix it. All this means there could be a degradation of the study, and the results wouldn’t be accurate enough to make informed decisions.

Additional Resources

Learn more about the epilepsy services at NewYork-Presbyterian.

Learn more about The Epilepsy Center at Weill Cornell Medicine and NewYork-Presbyterian.