What is Multiple Myeloma?

An oncologist explains how multiple myeloma, a rare blood cancer, is diagnosed and treated.

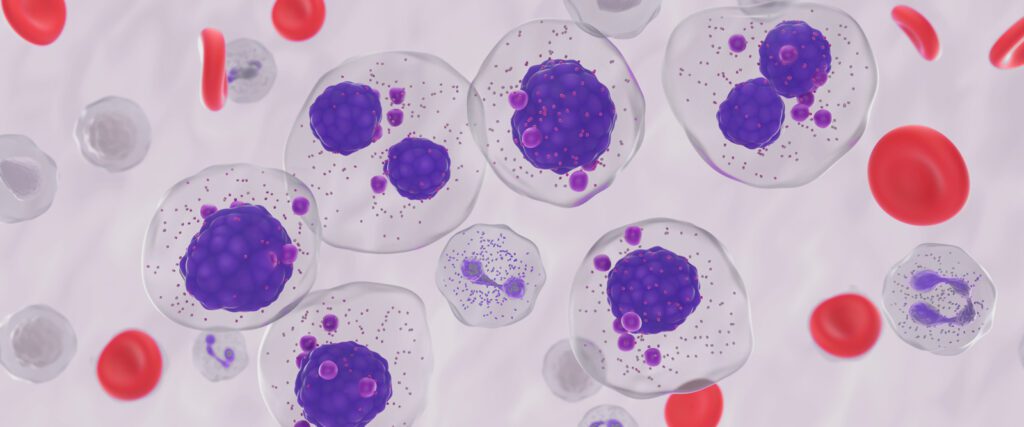

Plasma cells, a type of white blood cell made in the bone marrow, play a key role in helping our immune systems fight off infection. But these cells can grow out of control and become cancerous, a disease known as multiple myeloma, explains Dr. Suzanne Lentzsch, an oncologist and the director of the Multiple Myeloma and Amyloidosis Program at New York-Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving Medical Center. “These abnormal plasma cells produce antibodies that are not able to protect the body from infections like normal ones do,” says Dr. Lentzsch. Besides having an increased risk of infection, people with multiple myeloma may be prone to developing other conditions like bone fractures, anemia, and kidney failure.

Multiple myeloma is a rare blood cancer that affects less than 1% of people and has a five-year survival rate of 61%, according to the American Cancer Society (ACS). In the fall of 2024, multiple myeloma made news when Patti Scialfa, Bruce Springsteen’s wife and bandmate, revealed she has been living with this type of blood cancer since 2018.

In recognition of Multiple Myeloma Awareness Month in March, Health Matters spoke with Dr. Lentzsch to understand how multiple myeloma affects the body, risk factors for the disease, and how it is diagnosed and treated.

What happens in the body when multiple myeloma occurs?

Dr. Lentzsch: Normal plasma cells produce antibodies called immunoglobulins, which are proteins that protect our bodies from infection. The overgrowth of abnormal plasma cells produces antibodies called monoclonal proteins (M proteins). These antibodies are not able to fight infection. And when there are large amounts of abnormal plasma cells, other important cells in our bodies are crowded out, including red blood cells, which are responsible for carrying oxygen throughout our bodies; platelets, which help heal bruising and stop bleeding; and other white blood cells that also fight off infection.

It is important to note that the presence of M proteins in the blood does not mean that someone has multiple myeloma. These abnormal proteins can also be a sign of other plasma cell disorders, such as MGUS (monoclonal gammopathy of uncertain significance) or smoldering multiple myeloma. However, both disorders are risk factors for multiple myeloma and considered pre-stages of the disease. They tend to be detected by accident through blood tests ordered to look for other health conditions.

Can you tell us more about MGUS and smoldering multiple myeloma?

MGUS occurs when abnormal plasma cells produce a small number of M proteins, but this disorder is not cancer, and people with MGUS do not experience any health effects or need any treatment. However, studies have shown that there is risk of MGUS progressing to multiple myeloma or other plasma or lymphoid malignancies. At 10 years, there was a 10% risk, and at 20, it was 18%.

Smoldering multiple myeloma is what MGUS usually progresses to. It’s when patients have more abnormal plasma cells in the bone marrow and higher levels of the M protein. While smoldering multiple myeloma does not cause damage to a person’s health, it is a pre-cancerous condition and people with the disorder have a 10% risk per year of it progressing to multiple myeloma.

These disorders take many years to transition to multiple myeloma, and sometimes occurrence of the disease may never happen. But because these plasma cell disorders are pre-stage conditions, we see patients with MGUS yearly to examine their overall health. Those with smoldering multiple myeloma need a tighter follow-up, such as every four to six months. This allows doctors to recognize any changes, signs, and symptoms of multiple myeloma so that we can treat them early on.

What are some other risk factors of the disease?

We see an increased risk of multiple myeloma if there is a strong family history of the disease. If people have several family members who have had the disease, I recommend they mention this to their doctors.

Other factors include age, gender, and race. People younger than 45 years old rarely develop multiple myeloma, and men are more likely than women to develop the disease. It is also more than twice as common among Black people than white people, according to the CDC.

What are the signs and symptoms?

About 10% to 20% of patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma do not experience symptoms, according to the Multiple Myeloma Research Foundation. When they do, symptoms include fatigue, bone damage and pain, kidney problems, and infections.

What tests help diagnose multiple myeloma?

Multiple myeloma is often diagnosed by doing lab tests, including complete blood count, blood chemistry tests, blood, and urine tests; physical exams; biopsies, such as of the bone marrow; and imaging tests, including X-rays, CT scans, and MRIs.

To establish a diagnosis, we would look at the results of several of these tests. We would need to see at least 10% plasma cells in the bone marrow, and one of several other factors, such as low red blood cell counts (anemia), bone lesions, high blood calcium level, or poor kidney function.

How is multiple myeloma treated?

In general, treatment includes four medications that are usually well tolerated by patients. They include monoclonal antibodies, man-made versions of antibodies that destroy malignant plasma cells, and proteasome inhibitors, which target and remove multiple myeloma cells. Both are given subcutaneously, or as an injection under the skin. Additionally, oral medications include immunomodulatory drugs, which break down proteins that are essential for controlling cell division, as well as steroids.

What advancements have been made in treating this disease?

The future of multiple myeloma treatment is very promising. In 2023, we had two new approvals of bispecific antibodies, which target tumor cells and engage T-cells, a type of white blood cell of the immune system. And then we have immunotherapy, such as CAR-T cell therapy, which genetically changes a person’s own immune cells to fight cancer.

We are also working towards a functional cure. Let’s say a patient is 70 years old. We might not cure them from multiple myeloma, but we might treat them until they reach their natural life expectancy. For example, if the natural life expectancy is 86, would we be able to keep the patient alive for 16 more years? We are on our way to switching it from a life-threatening disease to a chronic disease.

Suzanne Lentzsch, M.D., Ph.D., is an oncologist and the director of the Multiple Myeloma and Amyloidosis Program at NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving Medical Center. She is also a professor of clinical medicine at Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons.

Dr. Lentzsch is an internationally recognized expert in her field and cares primarily for patients with plasma cell dyscrasia, including MGUS, multiple myeloma, amyloidosis, POEMS syndrome, and Waldenstrom’s Macroglobulinemia.