What Is a “Mini-Stroke?”

A “mini-stroke” may not cause permanent brain damage, but it’s a warning sign that you could be at risk for a debilitating—or deadly—stroke.

Approximately one in three American adults has experienced a symptom consistent with a “mini-stroke,” sometimes called a transient ischemic attack (TIA). Yet, only 3 percent sought medical care, according to a 2017 study from the American Heart Association.

Ignoring these symptoms could have serious consequences, says Dr. Feliks Koyfman, a neurologist and director of stroke services at NewYork-Presbyterian Queens. Once you’ve had a TIA, there’s a 10 percent chance you’ll suffer a full-blown stroke within the next three months, says Dr. Koyfman. However, he notes that the greatest risk is in the first 48 hours to seven days after a TIA. In fact, five people out of a 100 who have had a TIA will have a stroke within just two days.

“People might minimize the event because a ‘mini-stroke’ often resolves quickly, but it’s still an emergency that needs to be evaluated,” he says. “The best way to prevent future strokes is if a person acts quickly so we can determine and treat the underlying cause.”

Ahead of World Stroke Day, Health Matters spoke with Dr. Koyfman, who is also an assistant professor of clinical neurology at Weill Cornell Medicine, about how to spot the warning signs of a TIA, what to do after someone suffers one, and ways to reduce the risk of having a stroke.

What is TIA?

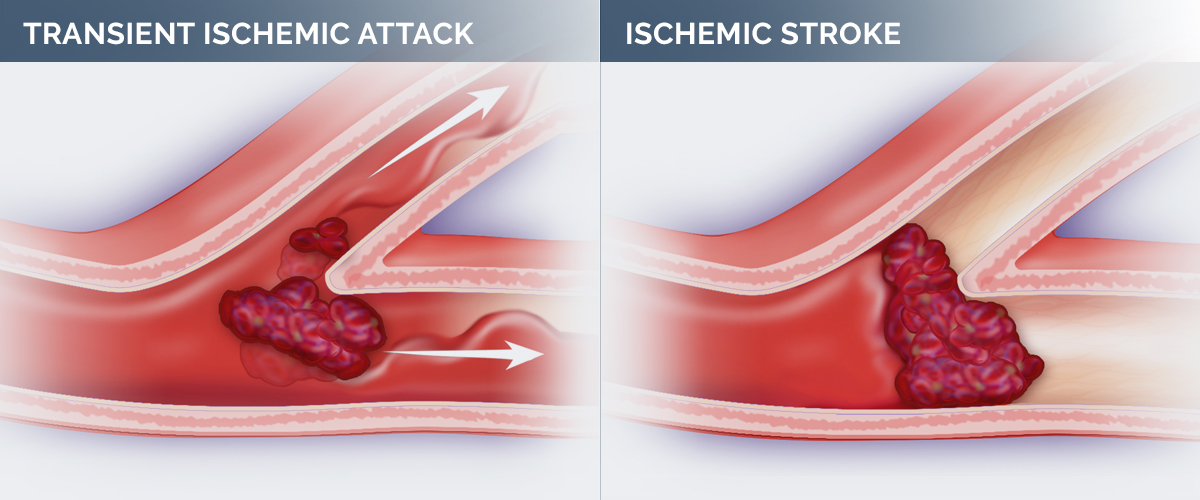

TIA stands for transient ischemic attack, sometimes known as a “mini-stroke.” Most strokes are due to a blockage in a blood vessel that leads to an injury in the brain. A TIA is like a stroke that stopped before any permanent damage was done. This means there is a temporary cessation of blood flow causing dysfunction of the brain, but the blood flow is restored before there’s permanent damage to the brain.

u003cstrongu003eWhat’s the difference between a TIA and a full-blown stroke?u003c/strongu003e

With a TIA, the symptoms are usually short-lived. The person might have a drooping face and weakness of the arm on the same side of the body, but those symptoms will often last only 5 to 10 minutes, go away and the person will look and feel completely normal. With a full-blown stroke, the decrease in blood flow goes on for a longer period of time.

What we’ve learned, though, from more modern imaging techniques like MRI — which is sensitive to the earliest signs of a stroke — is that even people who have very brief spells, can have evidence of permanent damage to the brain about half the time. So, these brief spells that we used to call TIAs are now actually referred to as strokes if an MRI shows signs of scarring on the brain. The important thing is finding out what made this spell happen and what we can do to prevent the person from having a potentially large, disabling stroke.

u003cstrongu003eIf the symptoms resolve quickly, how does a person know they’ve suffered from a TIA and not something less dangerous?u003c/strongu003e

A TIA is a transient event that, by definition, resolves within 24 hours. Because the symptoms frequently go away within minutes or in under an hour, people may assume everything is okay. For that reason, they may attribute their symptoms to something else, like a migraine, a pinched nerve or an inner-ear issue that causes dizziness. When the symptoms are new or different from anything that you’ve experienced before, if they’re severe, or if they come on very suddenly, it’s important to seek medical attention right away.

If you can’t come up with an obvious alternative explanation for your symptoms, then you should go to the emergency room and get it checked out because it can be the first sign of a more serious problem. Unfortunately, there’s no real way to know for sure unless you get it checked out.

u003cstrongu003eDo we know what causes a TIA?u003c/strongu003e

There are many different causes of a TIA, and the causes are essentially the same as those for stroke and heart disease. High blood pressure is the most important cause of strokes and TIAs. Heart diseases are also a common cause of stroke, especially heart rhythm disturbances like atrial fibrillation or an irregular heart rhythm. What happens in that situation is that the heart is not beating regularly, so instead of the blood flowing quickly through the heart, it can form little eddy pools, like whirlpools, inside the chambers of the heart. Those eddy pools can lead to the formation of blood clots. Those little blood clots can travel through the blood vessels, and when they get into a small enough blood vessel in the brain, they block it and stop the blood flow, causing a stroke.

Another major cause is a narrowing in one of the arteries of the brain, particularly the carotid artery that comes up from the neck. This is the blood vessel that everybody can feel pulsing in their neck, carrying blood to the brain. A narrowing in a blood vessel is called a stenosis. With time and aging and certain risk factors, like high blood pressure and diabetes, the carotid and other vessels can narrow, and this leads to decreased blood flow to the brain. Sometimes it closes off completely and that can then lead to a stroke.

u003cstrongu003eWho is most at risk for a TIA?u003c/strongu003e

People who have high blood pressure, diabetes, high cholesterol, inflammation or who smoke and have a sedentary lifestyle are at risk. All of these conditions can gradually lead to damage to the heart or blood vessels over time.

There is also a misconception about strokes and TIAs that they only affect older people. We have seen an increase in strokes in younger people as well. We think part of the reason for that is a change in the occurrence of risk factors in younger people. There’s an obesity epidemic in the country, and there’s a lot of sedentary behavior. People aren’t getting enough activity and exercise. So, we’re seeing the occurrence of conditions like high blood pressure and diabetes in younger and younger people. Along with that come complications, which include strokes and TIAs.

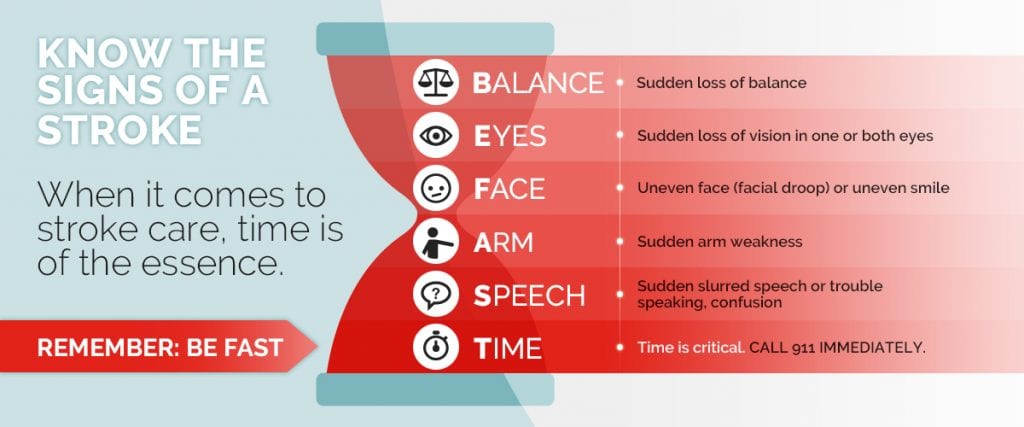

Additionally, according to a 2020 study from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, one third of adults in the United States don’t know all five of the most common symptoms of a stroke, which are trouble speaking, problems with balance, vision problems, facial asymmetry and weakness or numbness in one’s arm or leg. So, at the public health and national level, education about risk factors and symptoms is extremely important.

“People might minimize the event because a ‘mini-stroke’ often resolves quickly, but it’s still an emergency that needs to be evaluated.”

Dr. Koyfman

u003cstrongu003eHow do you treat a TIA?u003c/strongu003e

When somebody shows up in the emergency room with symptoms that may be consistent with a TIA or stroke, they will get a CT scan of the head. The main reason is to rule out bleeding in the brain, known as a hemorrhage. Strokes come in two major varieties. One is blockage in the blood vessel, called an ischemic stroke. The other is a hemorrhagic stroke, which is due to bleeding in the brain from a ruptured blood vessel.

If there’s no evidence of bleeding and the symptoms are persisting, the patient will be treated as though they are having a full-blown stroke, and they might be a candidate for thrombolytic therapy, or tPA, which is a medicine that can dissolve blood clots. They would need to get that within a few hours after the stroke occurs to be effective. They will also have more imaging of arteries in their head and neck, and if these tests show evidence of severe blockage in a blood vessel, then the person might need an interventional procedure — known as a thrombectomy — which is the removal of a blood clot from that large blood vessel in the brain.

What should I expect as a treatment plan after I leave the ED or doctor’s office?

Even after a thorough evaluation, about a third of strokes are of undetermined cause. It is believed that most of those are likely due to a blood clot that came from the heart, but physicians haven’t pinned down the cardiac problem that caused the clot. The standard of care is to have the patient take antithrombotic medications, such as aspirin, to thin the blood, and a cholesterol-lowering medicine or blood pressure medicine, if needed. About 30 percent of patients who suffer from an unexplained stroke will eventually have evidence of a heart rhythm disturbance like atrial fibrillation, but that means about 70 percent won’t.

Additional treatments could include stronger blood thinners, or, if imaging shows the person has carotid artery stenosis, surgery or stenting can be done to improve blood flow through the artery.

How can someone reduce their risk of having a stroke or TIA?

There are a lot of great ways to prevent having a stroke. Leading the pack is physical activity. The American Heart Association recommends 150 minutes, or 30 minutes for five days a week, of at least moderate intensity aerobic exercise, such as riding a bike, jogging or playing tennis. If you have arthritis or other issues where you may not be able to engage in this level of activity, you could walk for half an hour a day. Whatever you can do to get up and get moving is a great way to reduce the risk of a stroke.

Also, eating properly — I tell my patients to eat plenty of fruits and vegetables. Avoid concentrated sweets and processed foods. For protein, fish is good. Poultry is good, especially if you take off the skin, and limiting red meat ideally to no more than one time a week. Drink water as much as possible. Seltzer is good, too. Avoid sugar-sweetened beverages. Even diet sodas and diet drinks may carry some risk with them. With regard to alcohol, we tell people no more than one glass of red wine day for women and no more than two glasses of red wine a day for men, and beer and hard liquor should be avoided.

I recommend getting your blood pressure and cholesterol levels checked and making sure that you’re not developing problems with blood sugar. And, of course, avoid smoking any tobacco products. We’ve seen the kinds of problems that vaping can cause to the lungs. And any tobacco products are potentially risky and should be avoided.

Feliks Koyfman, M.D., is the director of stroke services at NewYork-Presbyterian Queens and an assistant professor of clinical neurology at Weill Cornell Medicine. Dr. Koyfman is a member of the American Academy of Neurology, American Heart Association, and the Stroke Council, and has clinical expertise in treating acute ischemic strokes, intracranial hemorrhages and subarachnoid hemorrhages, as well as stroke prevention.

Additional Resources

Learn more about stroke services at NewYork-Presbyterian.