Award-Winning Artist Noma Bar’s New TAVR Ad

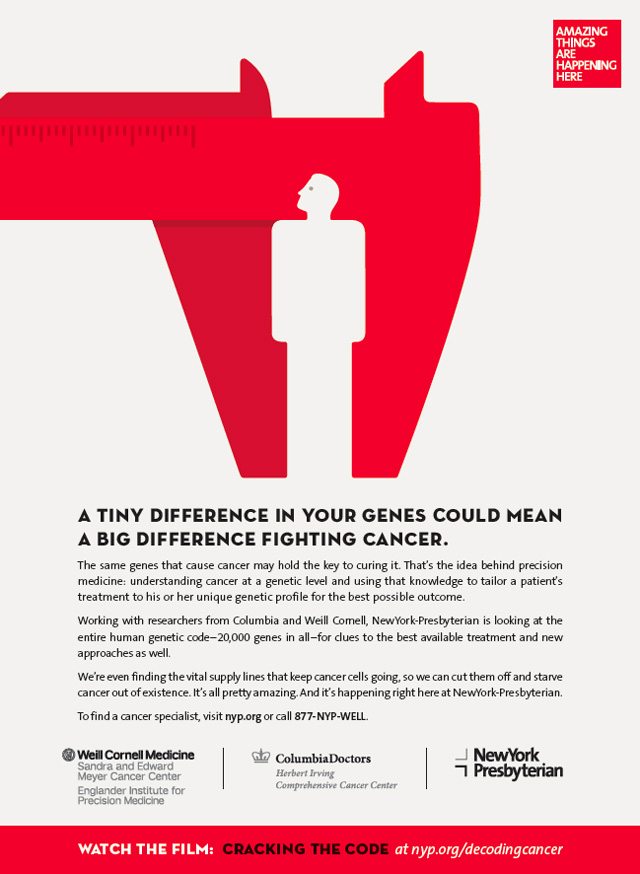

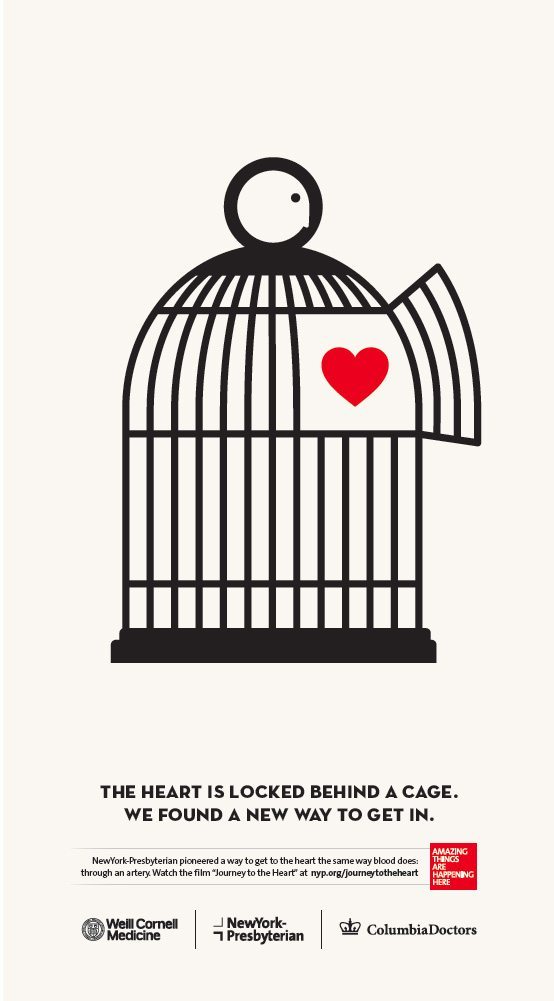

The acclaimed designer behind NewYork-Presbyterian’s ads that bring to life breakthroughs in cardiac and cancer care.

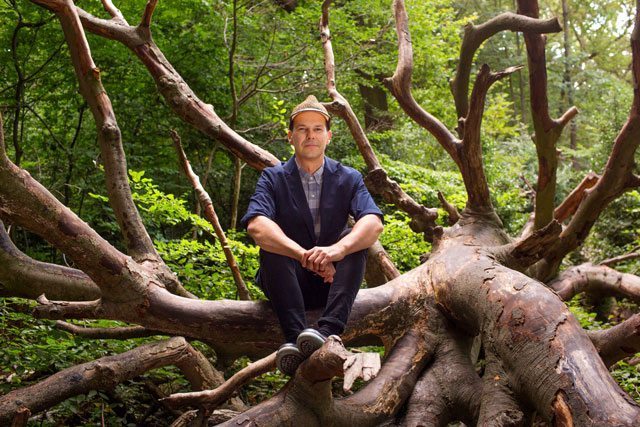

For renowned graphic designer, illustrator, and artist Noma Bar, most days begin the same way: He drops off his daughters at school, stops by a café, then heads to the office.

The office, in Bar’s case, is a 70-acre wood in northern London that dates to the Middle Ages. Here, sitting on moss-covered stumps shaded by ancient oak trees, the Israeli-born artist has spent 17 years sketching award-winning artwork, later completing it on his computer, including NewYork-Presbyterian’s animated ads explaining immunotherapy, precision medicine, and now TAVR (transcatheter aortic valve replacement).

“This is the best kind of work, the kind of work that can make a difference,” Bar says of the collaboration with NewYork-Presbyterian.

In the new television ad (shown above), Bar, 43, uses everyday objects — a pump, a car, a washing machine — or what is known as ready-made art, to make complex topics easy to understand.

In the TAVR ad, his mission was to explain a new minimally invasive procedure that has proved to be lifesaving for aortic valve stenosis patients who are not good candidates for standard valve replacement, which typically requires open-heart surgery. Aortic disease means that the valve opening is so narrow that blood flow is restricted.

Since the ad is intended to explain this latest advance in cardiac care, Bar, collaborating with animator Alejo Accini, of Ale Pixel studio, and sound designer Weston Fonger, of VINYLmix, with a script written by Steve Feinberg, of Seiden Advertising, began with a pump, an apt metaphor for the heart.

Taking out his sketchbook and a black felt pen, Bar began to illustrate how the handle of a pump morphed into a car, and a washing machine, without his pen leaving the page.

Early Days

Bar was just a boy when he discovered the power of the pen in his hand.

“I always loved drawing,” he says, recalling how his parents realized they could keep him quiet if they gave him a pen and paper.

One day during the Gulf War, Bar, then 17, was in a bomb shelter with his family when he noticed a black radioactive symbol on a yellow background in the pages of a newspaper.

“It struck me that it looked just like Saddam Hussein’s dark eyebrows and mustache,” he says of conceiving one of the images that gained him fame.

But it was his drawing of William Shakespeare, using a question mark to reflect “To be, or not to be,” that ultimately landed him his first commission for an iconic face from Time Out London.

Bar was born in Afula, Israel, during the Yom Kippur War. Even his early drawings included guns, tanks, soldiers, and symbols of war still seen in his work today.

After an unhappy stint in the Israeli Navy, Bar finally had the chance to pursue his dream of becoming an artist.

His family, which includes many artists, immigrated to Israel from Romania after the Holocaust. His father worked as an area inspector protecting the woods. Although Bar says he felt like an outsider joining his father in the forests, he is drawn to the woods now.

Bar, who recently released Graphic Story Telling, a midcareer retrospective featuring a collection of his work, studied typography at the Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design in Jerusalem. After moving to London with his wife, Dana, he could no longer use the written word to express himself as an artist.

“I needed to find a new way to communicate, so I came back to early things I did, like faces,” he says. “Like an actor that moved to a different country and cannot play in his language on the stage, I couldn’t say things in Hebrew, but I wanted to say things, so I started to do almost like Charlie Chaplin, communicating without words.”

Bringing Complex Surgery to Life

That method informs his work for NewYork-Presbyterian.

“It’s a little like Pac-Man. I’m eating the next one all the time, just like going through a maze,” he says, explaining how he transitions naturally from one object to another.

“You want to get to the other side, but it always starts with the red square,” he says of his work for NewYork-Presbyterian, referring to the hospital’s iconic red box touting “Amazing Things Are Happening Here.”

As a graphic designer, you have the power to make a statement, to grab people’s attention.

Noma Bar

Given the promise of TAVR, pioneered at NewYork-Presbyterian, doctors stress the importance of spreading the word about it.

“Aortic stenosis is largely a disease of aging, and older patients are not good candidates for open surgery due to a variety of age-related illnesses,” explains Dr. Marty Leon, the director of the Center for Interventional Vascular Therapy at NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving Medical Center and a professor of medicine at Columbia University Medical Center.

“The underlying disease, aortic stenosis, has a devastating prognosis with up to a 50 percent mortality in the first year after symptoms,” he continues. “We’re now offering an opportunity to have an easier, safer procedure that could be applied more broadly to many more patients who otherwise might not have been candidates or who are at high risk with the expectation of equivalent results.”

Dr. Arash Salemi, the surgical director of the Acquavella Heart Valve Center at NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center and the Carrie and David Landew Associate Professor of Cardiothoracic Surgery at Weill Cornell Medicine, says: “The exciting things about the technology are, one, that we are able to treat a wider range of patients than we otherwise would have with just open-heart surgery. We have more options for our patients. Also, it’s less invasive physiologically than open-heart surgery. Because of that, recovery is quick. You see patients rebound and go home. They’re doing what they wanted to be doing two weeks ago. They’re doing it now without a problem. It’s very gratifying.”

Bar is happy to help spread the word.

“As a graphic designer,” he says, “you have the power to make a statement, to grab people’s attention.”