Three New Organs, One New Life

One year after undergoing a 23-hour triple transplant that gave him two new lungs, a liver, and a kidney, 25-year-old Raymond Fermin says, “I wake up every day feeling grateful that I’m still here and that I can breathe now.”

Raymond Fermin just landed a shot at a basketball court near his home in the Bronx. He is messing around with his best friend, Bernie Fabre, as they dribble past one another, drive to the basket for a layup, and scramble for rebounds.

After about 20 minutes, Raymond takes a break, not to catch his breath but to drink some water and revel in the fact that he’s back on the court.

“Before, when I was sick and playing basketball, I wouldn’t last too long,” recalls the 25-year-old. “Now I can actually play at my pace, and I don’t have to give my spot up during a game.”

There was a time when Raymond had to witness life from the sidelines. Born with an aggressive form of cystic fibrosis — a genetic disorder that affects the lungs, pancreas, and other organs — Raymond started experiencing trouble breathing as a teenager. By age 23, cystic fibrosis had ravaged Raymond’s body, causing multiorgan failure and leaving him with limited breathing capacity, recurrent lung infections, cirrhosis in his liver, and advanced kidney disease that led to dialysis.

“His quality of life was terrible,” says Dr. Emily DiMango, the director of the Gunnar Esiason Adult Cystic Fibrosis and Lung Program at NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving Medical Center. “He had frequent infections and needed frequent hospitalizations. It was getting increasingly difficult to keep him stable.”

That all changed after Raymond underwent the first-ever triple transplant at NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving Medical Center, receiving two lungs, a liver, and a kidney from one deceased donor. Raymond is the first lung-liver-kidney transplant patient in New York State and only the third such case reported in the United States, according to the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network database. The 23-hour surgery started in the evening of July 16, 2020, and stretched into the next day, with a care team of more than 20 working around the clock to do their part.

“This transplant involved every team imaginable: our cystic fibrosis team, the lung team, the kidney team, the liver team, anesthesiology, the ECMO team, the cardiothoracic ICU team, who would care for him after surgery. It really does take a village, and there is no way we would have been successful in Raymond’s care from beginning to end without this multidisciplinary approach,” says Dr. Lori Shah, a transplant pulmonologist at NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving Medical Center and one of Raymond’s doctors.

Now, one year after his groundbreaking triple transplant, “I wake up every day feeling grateful that I’m still here and I can breathe now,” Raymond says. “I’ve been given a second chance.”

“I Was Missing Out”

Growing up with his mom, Griselda Aracena, and his little sister, Adrianna, “I didn’t actually notice my cystic fibrosis,” says Raymond. “I would play tag with my friends. We would run around, ride bikes, climb things.”

Raymond with his little sister, Adrianna.

“He would always go outside and play,” adds Adrianna, 20, who was also born with CF and underwent a lung transplant at NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving Medical Center in 2018. “He was very outgoing.”

Cystic fibrosis, however, is a progressive disease that causes mucus to build up in your lungs, which leads to breathing problems. As a patient gets older, the condition can cause persistent lung infections that lead to scarring in the lungs and limit one’s ability to breathe. It can also affect the digestive tract and the body’s ability to absorb key nutrients from food. More than 30,000 people in the U.S. have cystic fibrosis, and the disease is the third-leading cause for lung transplants in the country.

When Raymond hit his late teens, he started to cough more and would get run down easily. Soon, Raymond — who also developed cystic fibrosis-related diabetes — found himself winded doing everyday activities, from making his bed to playing basketball. “I saw all my friends running up and down, and I’d have to catch my breath, or sometimes I’d sit out the game,” he says.

“When he started telling me he really couldn’t play basketball, that really struck me,” says Dr. DiMango, who met Raymond in 2017 when he transitioned from the pediatric to the adult cystic fibrosis program at NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving Medical Center. “That was not only exercise, but his social life.”

In 2018, Dr. DiMango referred Raymond to Dr. Shah to start exploring a possible lung transplant — a welcome conversation that Raymond was eager to have.

“I wanted to get out of my old self,” says Raymond. “I was always coughing and uncomfortable. When I would try to go out with friends, I would just want to go back home. I wouldn’t really be up for anything. I was missing out.”

The Triple Threat

In 2019, as Raymond’s pulmonary function continued to decline, doctors discovered that his lungs were not the only organs suffering from end-stage disease.

Liver disease has become more prevalent in cystic fibrosis patients, presenting in an estimated 20% to 40% of CF cases in recent years. As a precaution, Dr. Shah asked Raymond to undergo a routine liver exam as part of his lung transplant evaluation. That’s when doctors discovered severe cirrhosis.

“We all have more liver than we need. Raymond had enough good liver to do everything the liver needs to do, but it would not have been enough to take him through the difficulty of a lung transplant,” says Dr. Lorna Mills Dove, director of Clinical Hepatology at NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving Medical Center and medical director of Adult Liver Transplants at the Center for Liver Disease and Transplantation at NewYork-Presbyterian. Plus, “a liver that’s scarred puts you at risk for increased infection post-transplant.”

As doctors began to discuss a possible lung-liver transplant, Raymond had a kidney biopsy that revealed extensive chronic renal disease from IgA nephropathy, an inflammation in the kidneys that is not normally associated with CF patients.

“There are patients who’ve received combined lung-liver transplants, but having underlying advanced kidney disease makes it more likely that the patient will have major complications,” explains Dr. Geoffrey Dube, a transplant nephrologist at NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving Medical Center. “Doing two organs at the same time would only fix two-thirds of the problem.”

By the fall of 2019, the three transplant teams reached the same conclusion: Raymond needed a simultaneous lung-liver-kidney transplant in order to give him the best chance for a successful recovery.

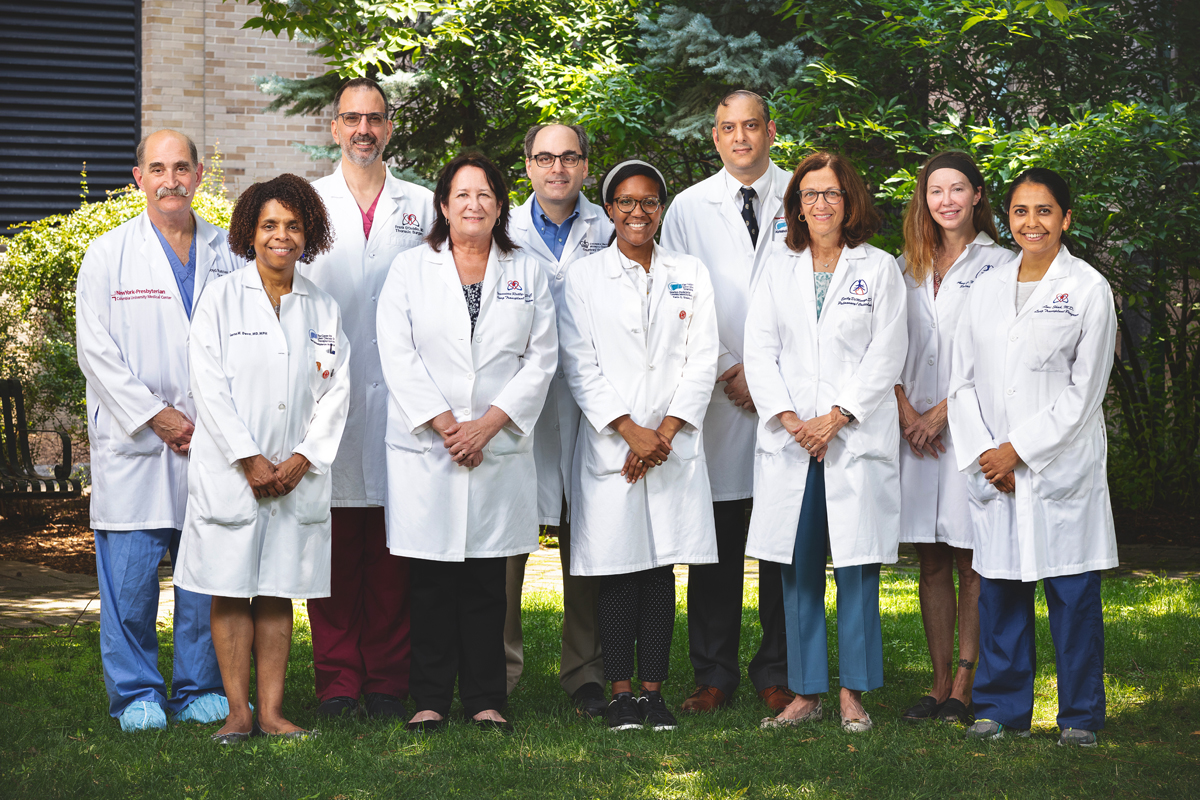

Meet Raymond’s Care Team

A multidisciplinary team from NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving Medical Center worked together to perform the first lung-liver-kidney transplant in New York State.

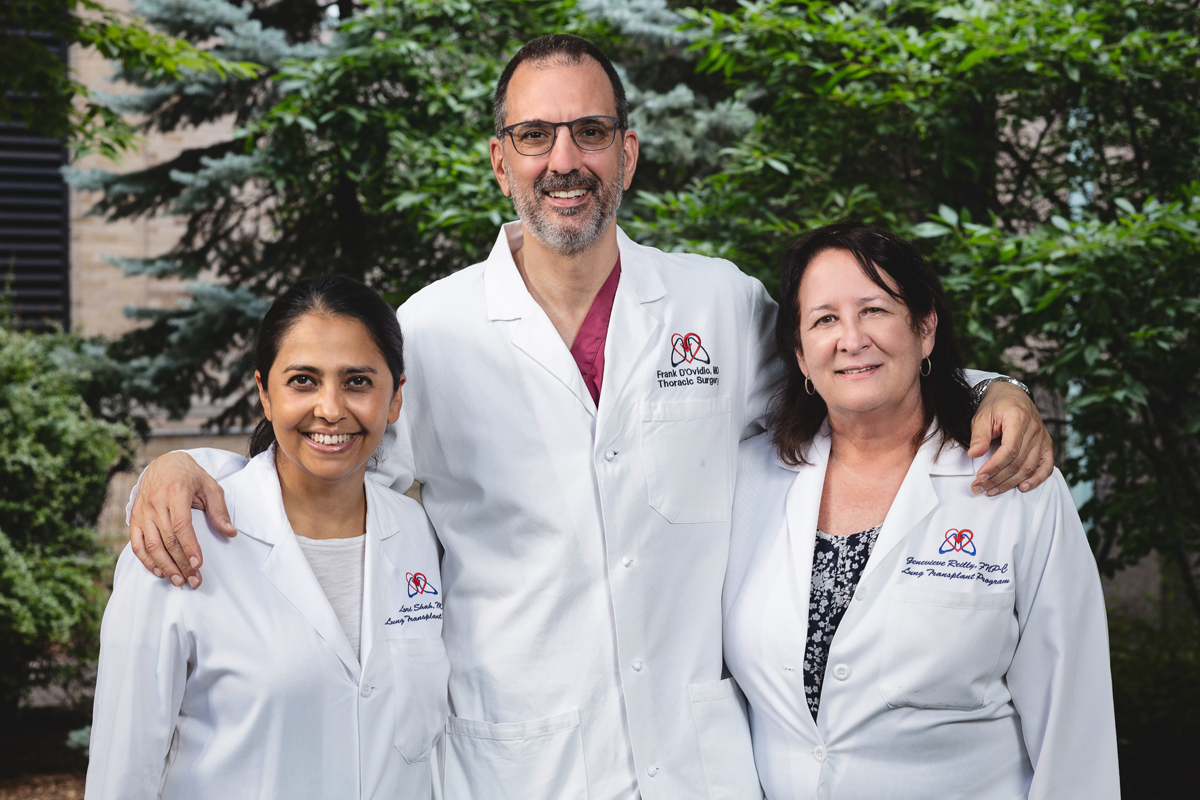

Lung Transplant Team

(from left) Dr. Lori Shah, Dr. Frank D’Ovidio, and nurse practitioner Genevieve Reilly.

Liver Transplant Team

(from left) Nurse practitioner Karin Shears, Dr. Abhishek Mathur, and Dr. Lorna Dove.

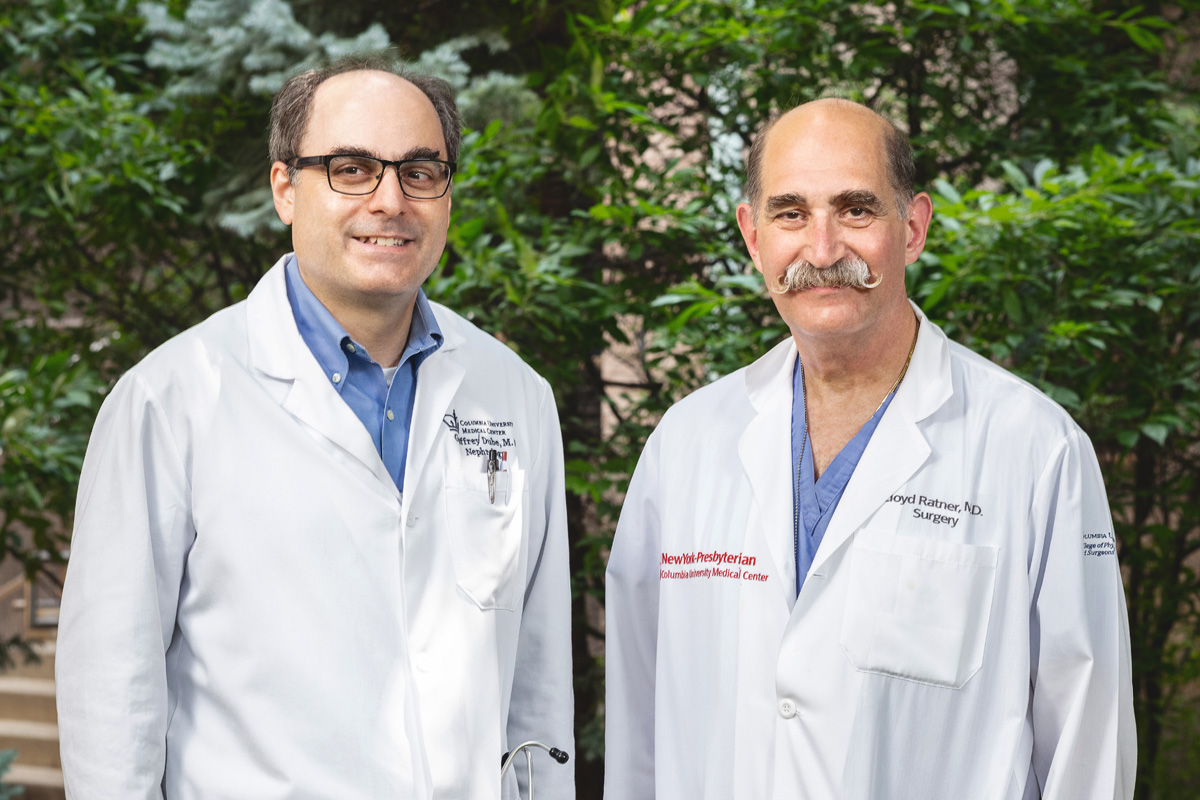

Kidney Transplant Team

Dr. Geoffrey Dube (left) and Dr. Lloyd Ratner. (Not pictured: Nurse practitioners Mia Boehler and Olga Pawliczak.)

Cystic Fibrosis Team

Nurse practitioner Amy McLaughlin (left) and Dr. Emily DiMango.

“In the beginning, I thought it was only going to be the lungs,” says Raymond. “Then when they started letting me know that they might need to do the liver, I was like, ‘We have to do what we have to do.’ Then when it was three organs, that’s when I probably had some fear. Three organs is a lot. But there were really no good options.”

Raymond’s care team, however, was determined to create the best option for him — though a triple transplant had never been performed at NewYork-Presbyterian. “We basically had to invent a surgical protocol for Raymond,” says Dr. Shah.

“One of our key jobs is to be able to give people hope,” adds Dr. Lloyd E. Ratner, director of the Renal and Pancreatic Transplant Program at NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving Medical Center. “It’s important for people who have complex medical problems not to lose hope, because there are people and institutions, particularly ours, that are willing to take on the most difficult problems.”

To that end, it took significant effort to work out the details around the novel procedure with multiple meetings to discuss everything from the procurement of the donor organs, to the order that the transplants would take place, to how post-op rounds would work. “This involved multiple planning sessions with a detailed discussion of each phase of care,” says Dr. Abhishek Mathur, a liver transplant surgeon at NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving Medical Center.

Raymond was always kept in the loop on the team’s progress. “He was on top of what’s going on,” says Dr. Shah. “He’s his own No. 1 advocate. He has taken responsibility and ownership of his medical issues for a long time.”

Adds Dr. Dove, “Raymond was persistent and a very active participant in his care. I would say, ‘You’ve got to do this,’ and he would reply, ‘Let’s do it.’”

And in the face of any obstacle, Raymond has remained resilient. “He deals with the challenges and doesn’t feel sorry for himself,” says Dr. DiMango. “He goes forward.”

A Race Against Time

His resolve was tested when COVID-19 descended on New York City last March — right as the team was about to clear him for the transplant waitlist.

“COVID put everything on hold because the whole world was on hold,” says Dr. Dove. “There were just too many unknown variables to do a transplant safely, and that delayed when we felt comfortable activating him on the transplant list.”

The delay was “very frustrating,” Raymond admits. “I was mad, depressed — a lot of emotions were running through me. I even cried because I’m already very sick.”

While his transplant was on pause, Raymond’s health continued to deteriorate during the pandemic.

“I was coughing up a lot of mucus. I was barely able to breathe, and I was using oxygen. Even sleep was hard; every hour I would wake up coughing,” says Raymond, who was also undergoing dialysis three times a week for up to four hours per session. “I didn’t want to do anything but lay in bed.”

“I never planned for my future, because I didn’t think I was going to make it this far … Now I can actually dream.”— Raymond Fermin

In June 2020, Raymond got “the best news”: His care team felt confident that the time was right, and they could safely add him to the transplant waiting list.

A few weeks later, on the evening of July 15, Raymond experienced severe bouts of coughing and was struggling to breathe more than usual. His mom insisted he head to the hospital, where he then started to cough up blood, a serious condition sometimes seen in patients with advanced CF lung disease.

He was immediately admitted to the ICU overnight, because “on top of everything else, Raymond now had life-threatening bleeding from his lungs,” says Dr. DiMango, who noted that his lungs were only functioning at 20 percent capacity. “We knew his time was limited.”

The next morning, “we get a phone call from the hospital saying Raymond is in really bad shape, and our hearts dropped,” recalls his sister Adrianna.

Serendipitously, on that same morning, a text chain among Raymond’s care team lit up with an urgent message: There was a possible match for Raymond.

“When I woke up in the ICU, my mom and my sister were already in the room,” recalls Raymond. “I remember someone came in and told us about the possible donor, and we all started crying.”

What happened next was a whirlwind. “I didn’t hesitate to sign the papers. I knew I was in bad condition, and this was a chance I had to take,” says Raymond.

Within three hours, word came back that the transplant was a go. “It happened so fast,” says Raymond, who was immediately wheeled into the operating room with hospital staff lining the hallways clapping. “My mother said it was a miracle.”

The triple transplant began at 6:32 p.m. with the removal of Raymond’s damaged lungs by Dr. Frank D’Ovidio, surgical director of the Lung Transplant Program at NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia.

“His lungs were as bad as they could get,” says Dr. D’Ovidio. “He didn’t have much more time to wait.”

Like a meticulously planned relay race, the team prepared for the triple transplant so that each surgeon would have enough time to implant their respective organ within the time frame it’s viable outside of the body. When the organ procurement team arrived at the hospital with the donor organs, Dr. D’Ovidio had to be ready to implant the lungs immediately, because they can only survive for six to eight hours outside of the body. Next came the liver, which is only viable for 10 to 12 hours once removed from the donor. The final transplant surgery was the kidney, which can last for up to 36 hours before being implanted.

For the entire surgery, Raymond was supported by ECMO, an extracorporeal membrane oxygenation machine that pumps blood and oxygen through the patient’s body. “We had planned to use ECMO so that we would not stress the heart and the new lungs, which are very delicate in the early post-transplant period, throughout three big surgeries,” explains Dr. D’Ovidio.

Throughout the day, the team remained in constant contact about the progress of each transplant. “When we’re planning to do a multiorgan transplant, we’re making multiple decisions along the way of whether or not to proceed with each organ. If ever the patient’s not stable or we think that the surgery poses too much risk, we’ll cut our losses, get the patient stabilized, and reallocate the organs so that someone else could benefit,” says Dr. Ratner.

During Raymond’s triple transplant, “we were monitoring every step of the way. We were stopping in the operating room and seeing how they were doing,” says Dr. Ratner. “In this case, everything went smoothly and exactly the way we wanted it to go.”

Raymond post-transplant at NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia on Aug. 3, 2020.

Raymond’s early days recovering in the cardiothoracic ICU were a blur. “I remember I woke up and I still had a tube in my mouth, but I saw my sister,” says Raymond. “I was pretty weak. The only thing I could do is move my head and pick up my arm a little bit.”

After a few days, his breathing tube was removed and Raymond was able to take his first breath on his own with his new lungs. “A nurse had to teach me how to breathe and to take it slow,” he says. “I noticed that I wasn’t straining and I was breathing easier. That’s when I really started to realize that I’m on the other side, and I made it.”

In that moment, Raymond noticed Dr. Shah standing about 10 feet away in his hospital room. “I was just watching, not even interacting or talking with him,” recalls Dr. Shah. “He saw me, our eyes met, and the first thing he did was give me a very slow thumbs-up. At that moment I think we both felt like, ‘We got through this and we’re going to be OK.’”

Back in the Game

Raymond spent 38 days —not to mention his 24th birthday on July 31, 2020 — in the hospital, recovering from his surgery and regaining his strength. “I had to learn how to sit up, how to grab things again, how to walk,” he says.

When he was discharged in August, “I cried when I saw the sun outside,” Raymond says. “I was still weak, but I was excited and relieved that I could go home and be with my family.”

With the help of physical therapy at home three times a week to help build muscle in his core and legs, Raymond was able to return to the basketball court within six months of his triple transplant. “The first time stepping back on the basketball court after the transplant, I was only able to shoot. I couldn’t really jump, and I had to play at a slow pace,” says Raymond.

Raymond nine months post-transplant near his home in the Bronx, N.Y.

Now one year post-transplant, “I’m able to run. I’m lifting weights slowly,” says Raymond, who also started riding a bike again and landed a new job working at a car service company in the Bronx. “I don’t want to say I’m 100 percent, but I can do more.”

Raymond continues to see Dr. Shah for follow-up care every month. Dr. Shah then touches base with Dr. Dove and Dr. Dube after each visit to review Raymond’s progress. “The idea is that our team, the kidney team, and the liver team will be there hand in hand with Raymond to make sure that all those wonderful things he experiences continue to be safe environments for him and that the health of his new organs can be maintained,” says Dr. Shah. Raymond also sees Dr. DiMango several times a year to monitor the cystic fibrosis that remains in his digestive tract.

For the first time in his life, the possibilities for Raymond seem endless. “I never planned for my future, because I didn’t think I was going to make it this far,” says Raymond, who wants to be an entrepreneur one day. “Now I can actually dream.”

And if any doubt ever creeps in, he simply reflects on his perseverance over the past year. “When I look at my scars today,” he says, “I’m always reminded that I’m a fighter — and to never give up.”

Additional Resources

To learn more about transplant services at NewYork-Presbyterian, visit nyp.org/transplant.