Esophageal Cancer On the Rise: What To Know

Gastroenterologist Dr. Felice Schnoll-Sussman discusses how to spot the signs.

Up to 15 million Americans experience heartburn daily, which occurs when excessive acid from the stomach splashes up into the esophagus. It is often caused by overeating, drinking caffeinated beverages like coffee, or the frequent consumption of spicy food or tomato-based products. Lying down with a full stomach or eating close to bedtime can cause heartburn as well. For most, this results in occasional, mild discomfort that subsides.

But if that heartburn persists and occurs more than twice a week, it may signal something more serious, such as gastroesophageal reflux disease, or GERD. Over time, this reflux process can change cells and damage the esophagus, possibly leading to esophageal cancer.

In 2018, it is estimated that over 17,000 cases of esophageal cancer will be diagnosed. That’s a 600 percent increase over the past 35 years, due in part to heartburn, reflux, fatty foods, and fast foods. If it’s detected early, however, it can be treated and possibly cured.

Dr. Felice Schnoll-Sussman, a gastroenterologist and the director of the Jay Monahan Center for Gastrointestinal Health and an associate attending physician at NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center, weighs in on what types of esophageal cancer to be aware of, who is at risk, and how to prevent reflux from turning into cancer.

Health Matters: What is esophageal cancer, and where does it occur?

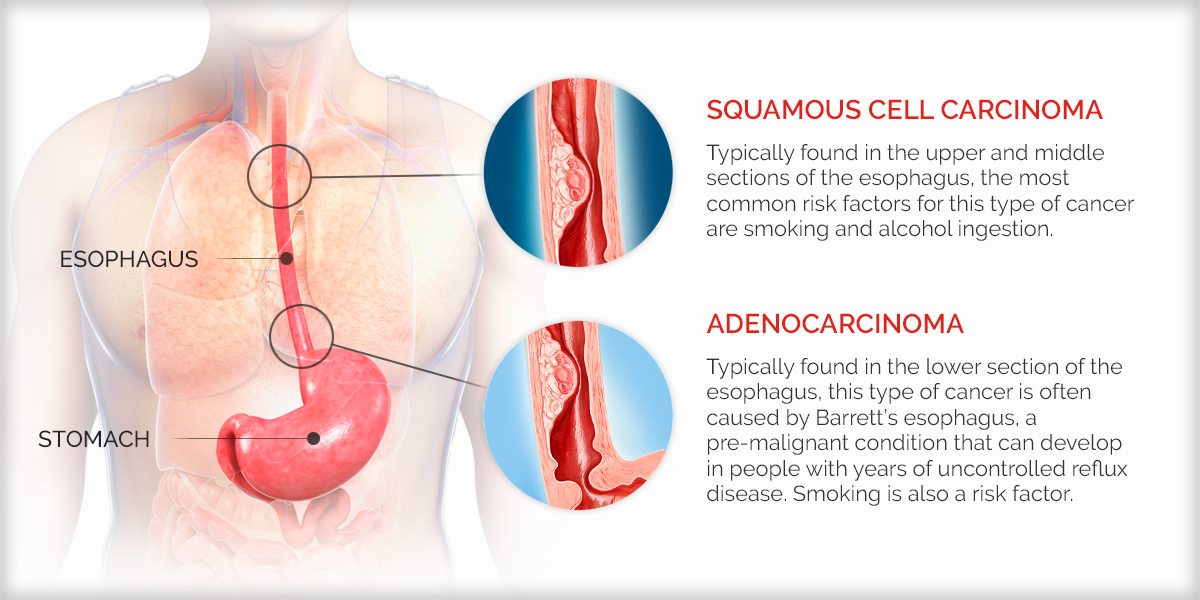

Dr. Schnoll-Sussman: There are two types of esophageal cancer: adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma. Adenocarcinoma is located in the bottom third of the esophagus. Squamous cell cancer is typically in the middle and upper part. Both cancer types can be very serious.

What are the risk factors for esophageal cancer?

Adenocarcinoma is often caused by a premalignant condition called Barrett’s esophagus. We believe that people who develop Barrett’s are those with years of uncontrolled reflux disease.

Caucasian males over the age of 45 who have experienced reflux three or more times a week for several months are most at risk. That’s not to say women and other demographic risk factors aren’t in that group though.

The most common risk factors for squamous cell carcinoma are smoking and alcohol ingestion. Smoking is probably a risk factor for both of these cancers. But when you think about squamous cancer, we more often think about people who have smoking as part of their history. So if you do smoke, try to quit. If you do not smoke, do not start.

What are the signs of esophageal cancer?

Everyone can get occasional heartburn. But a significant change in reflux symptoms may be a cause for concern. If you’re getting reflux symptoms much more regularly than in the past, if symptoms are becoming much worse, or they’re not controlled with, let’s say, just the over-the-counter medications such as proton pump inhibitors (e.g., omeprazole — brand names Prilosec or Zegerid) and H2 blockers (ranitidine — or brand name Zantac), or if you’re starting to have difficulty, pain, or food caught when swallowing, you should visit a physician to get evaluated.

Reflux may not only affect the esophagus but also the throat. People may get a chronic cough or hoarse voice, or a change in their voice from reflux. And some can have pulmonary symptoms such as wheezing and chronic cough.

How is esophageal cancer treated?

When caught very early, there are opportunities to remove a lesion endoscopically, by carving out the cancerous cells. This may be able to avoid the need for a more extensive surgery.

With Barrett’s esophagus, many different technologies now can be offered endoscopically. These include burning or freezing the abnormal precancerous areas with a subsequent return of the lining to normal tissue. If someone’s cancer has grown deeper into the wall of the esophagus, they may require surgery to take out all or part of it. If the cancer has already grown through the wall of the esophagus or traveled to a lymph node or other organ, a patient may require chemotherapy or radiation.

Dr. Felice Schnoll-Sussman

Why do we need to raise awareness about esophageal cancer?

It’s very often diagnosed at a late stage because patients don’t present [symptoms] until they start to have difficulty swallowing — and that’s a late symptom of esophageal cancer.

Now, in terms of late presentation, there are those who take medications over the counter — and that’s potentially an issue. Individuals are able to treat their heartburn without a prescription. That may, at times, have them not present early on with symptoms. Since they can self-medicate, that could potentially shift the timing of diagnosis to somewhat later.

Do you believe that’s a concern?

Part of it is understanding what symptoms are related to reflux disease, and making people realize if their reflux disease doesn’t go away with a short course of over-the-counter medications to control acid production, they should visit their physician for evaluation. Not to say they have esophageal cancer, but it’s at least a symptom that we can recognize, to try to get someone to the doctor at a stage before they develop cancer.

Any words of advice for people concerned about reflux disease leading to esophageal cancer?

I always say to patients, above all else, have a sense of your own body. It’s not normal to feel food getting caught. If you all of a sudden start to feel that, you should visit a physician.

There are also so many advances in our ability to diagnose and treat these diseases at early stages. When I speak with patients who have late-stage esophageal cancer, very often they had symptoms for a while, and either they didn’t get to a physician to discuss them or they ignored them. The other common thing is they’re frightened. My mantra is “do not die of fear.”

Learn more about reflux disease and digestive health.

Felice Schnoll-Sussman, M.D., is a gastroenterologist and the director of the Jay Monahan Center for Gastrointestinal Health; the director of clinical operations for the division of gastroenterology and the interim chief of endoscopy; an associate attending physician at NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center; and an associate professor of clinical medicine at Weill Cornell Medicine.