Obesity in Older Women Tied to Dementia Risk

A recent study finds that, for older women, more belly fat could mean an increased risk for dementia later in life.

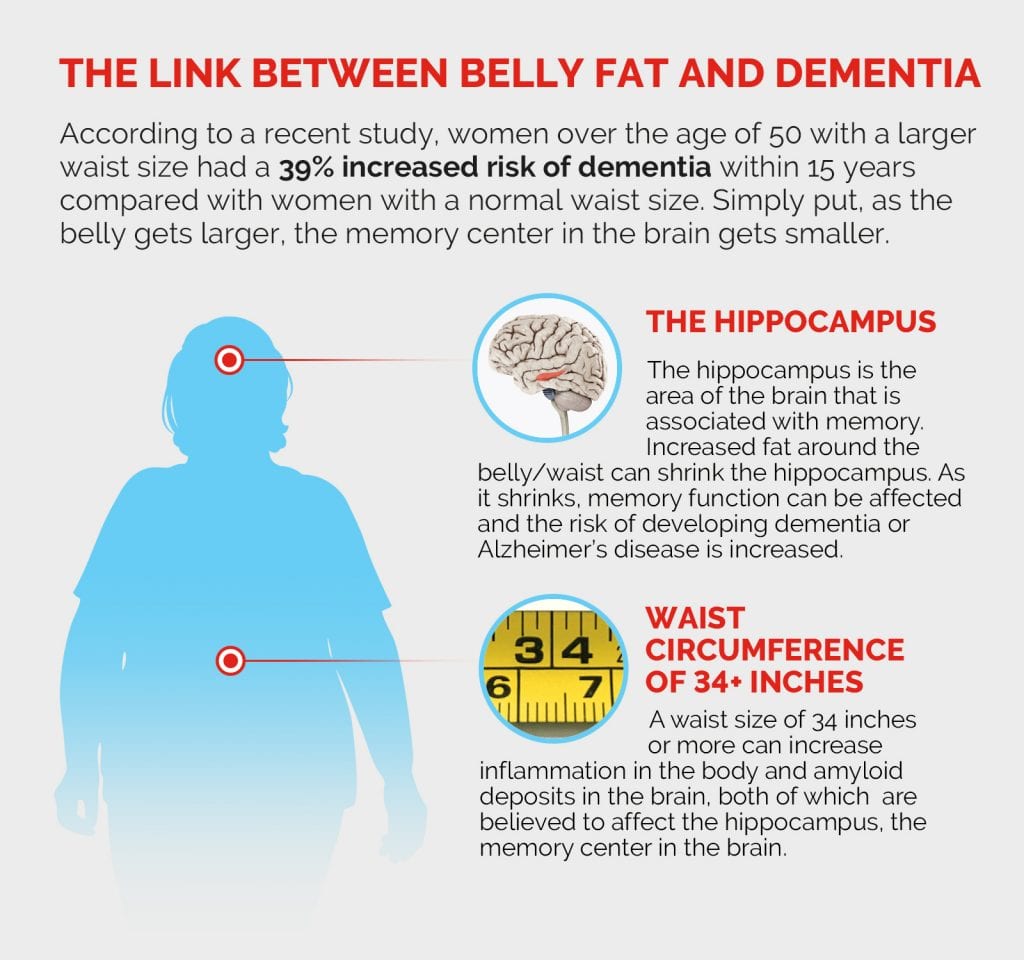

Both men and women who are obese and over 50 are at an increased risk for developing dementia later in life; for women with above average belly fat, that risk is particularly high. According to a recent study, older women with a larger waist size—more than 34 inches—had a 39% increased risk of dementia within 15 years compared with women with a normal waist size. Health Matters spoke with Dr. Richard Isaacson , a neurologist and the founder and director of the Alzheimer’s Prevention Clinic at Weill Cornell Medicine and NewYork-Presbyterian, about what can be learned from the study about the relationship between obesity and dementia, and what it means for women.

Health Matters: What surprised you about the study?

Dr. Isaacson: It’s actually not surprising at all to me. This study substantiated what I’ve been observing in my clinic for over a decade. We’ve made great strides in the last several years with Alzheimer’s disease and dementia research, and we’re discovering patterns among our patients that are shedding light on prominent risk factors — one of those being obesity.

Dr. Richard S. Isaacson

Why does obesity, particularly belly fat, put women at greater risk for dementia than men?

Medical conditions can affect men and women quite differently, and in terms of Alzheimer’s disease — the most common cause of dementia — that’s absolutely true. As we’ve seen in this study and in previous research, women who have elevated body fat, not just body fat throughout the body but body fat specifically around the belly, waist, and internal organs, tend to have a higher risk of dementia. In a study we published in 2019, we found that reducing body fat in people at risk of Alzheimer’s disease correlated with improved cognitive function.

How does waist circumference impact dementia risk?

Something I talk about all the time is, as the belly gets larger, the memory center in the brain gets smaller. Waist circumference is directly linked to the size of the hippocampus, the area of the brain that is associated with memory. I also commonly associate the words “metabolism” and “memory” in the same sentence, as the two are closely interrelated. Aside from a worsening metabolism, a poor diet, not enough exercise, and genetics can also lead to insulin resistance, which can develop into diabetes. People with diabetes have twice the risk of Alzheimer’s disease. Obesity-associated chronic inflammation can be responsible for lower insulin sensitivity, and the inflammatory cascade can cause damage throughout the body, brain, and belly. Also, insulin resistance literally fast-forwards amyloid deposits, plaque that builds up in the brain and impacts brain cell function, a biomarker for Alzheimer’s.

What does this mean for future dementia research?

We’ll need to further substantiate whether reducing body fat in the belly area lowers dementia risk and improves memory function. Based on my clinical experience, I would say of course it does. But we need to prove this now through rigorous studies. Our team at the Alzheimer’s Prevention Clinic is investigating this through a study we hope to publish soon.

Two out of three people affected by Alzheimer’s disease are women. Why does Alzheimer’s affect women more than men?

We used to say, “We don’t know,” but that’s not true anymore. Several factors are at play: It’s not just because women live longer, it’s not just because of the decrease in estrogen during menopause — which is very important and I’ll talk about that in a moment — it’s also due to a brain energy metabolism problem.

Just as there are metabolism changes in the body as you age, brain metabolism changes also occur. What we’ve seen through recent research is that certain hormonal risk factors like menopause can increase risk of Alzheimer’s from a metabolic perspective. During menopause, there are bioenergetic shifts in the brain that can trigger glucose hypometabolism (the inability to consume glucose), especially in people who are at the highest risk for Alzheimer’s.

We just published a new study that found that women who are undergoing perimenopause had higher amyloid deposits and their brain had trouble metabolizing sugar, the brain’s energy source, and had lower volumes of gray and white matter.

When should women be thinking about their brain health?

Alzheimer’s begins in the brain over 20 years before the first symptom of memory loss begins. So, if you have a family history of Alzheimer’s or a family member got symptoms of dementia starting at say, 55, then at least by 35 you should start getting serious about your health. If you have multiple family members with Alzheimer’s and the average age of the onset is 70, then at a minimum, you should start in your 40s.

But Alzheimer’s prevention, honestly, begins in the womb: The food and vitamin B content of what a mother eats while pregnant correlates with cognitive outcomes later on. Alzheimer’s is a life course disease, and the earlier someone pays attention to their brain health, the more of an impact they can make.

What can people do in their earlier years to stave off dementia in their later years?

Be proactive about your health. Take control of risk factors like high blood pressure, cholesterol, and diabetes, exercise regularly, consider switching to a Mediterranean diet, stress management, there are so many things. One out of every three cases of Alzheimer’s disease may be preventable if that person does everything right. That being said, some people will do everything right and still get Alzheimer’s, but research shows that people can really make a tangible impact on their trajectory away from Alzheimer’s by making healthy lifestyle choices.

Additional Resources

For more information on Alzheimer’s prevention, visit AlzU.org.

Learn more about brain health on Health Matters and read our “7 Tips to Help Prevent Alzheimer’s Disease.”

Richard Isaacson, M.D., specializes in Alzheimer’s prevention at NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center. He is the founder of the Alzheimer’s Prevention Clinic and the Weill Cornell Memory Disorders Program and is a trustee of the McKnight Brain Research Foundation. He is also the author of two bestselling books, The Alzheimer’s Prevention & Treatment Diet (with Christopher Ochner, Ph.D.) and Alzheimer’s Treatment, Alzheimer’s Prevention: A Patient & Family Guide.