Podcast: Honoring Black History and Family

Two NewYork-Presbyterian doctors discuss how their personal histories have shaped their careers and fueled their drive to provide equitable access to high-quality care.

While Carl Crawford and Solomon Iyasere never knew each other, they had many things in common. Both men immigrated to the United States around the same time (the late 1960s to early ’70s); both were athletes (Crawford represented Guyana in boxing in the 1960 Rome Olympics; Iyasere earned a soccer scholarship to SUNY New Paltz along with a Nigerian federal scholarship), and both instilled in their children the belief that “You’re going to do your best or not do it at all.” Those are the words that Crawford’s son, Dr. Carl Crawford Jr., and Iyasere’s daughter Dr. Julia Iyasere continue to live by in the work they do at NewYork-Presbyterian.

In honor of Black History Month, Dr. Iyasere, executive director of NewYork-Presbyterian’s Dalio Center for Health Justice, and Dr. Crawford, an attending physician at NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center and assistant professor of clinical medicine in the division of gastroenterology and hepatology at Weill Cornell Medicine, sat down with Health Matters to share the powerful story of how their fathers’ legacies inspire them to be better physicians and to help ensure that communities of color have more equitable access to high-quality care.

Listen to Health Matters Today

Informed and moved by their fathers’ experiences — and challenges — with the healthcare system, Drs. Crawford and Iyasere have both made building trust with their patients, particularly those from vulnerable populations, central to their approach. “As healthcare professionals, we have the opportunity to be recognized as a trusted source,” says Dr. Crawford. “We have to open up ourselves and we have to make sure that the community trusts us so that we can help them. [That’s what] they deserve.”

With communities of color impacted so severely by the COVID-19 pandemic, working to reach these populations is more urgent than ever. Dr. Iyasere has engaged in countless conversations with community members, especially as the COVID-19 vaccines roll out. “I think one of the things that we’re learning a lot of in the vaccine conversations is to meet people where they are and to say, ‘We recognize your history. We honor your approach. We just want to help support you in the decision,’” she says. “These conversations are the first step to building trust in communities.”

Highlights From Health Matters Today

On honoring their fathers

Dr. Crawford: I started college in 1992, and my dad was diagnosed with colon cancer in 1994. That was during the summertime. I was exposed to a hospital setting against my will, you can say. And I remember visiting an ICU for the first time to see my dad there. And it was very scary because here you have this ex-Olympic athlete who still trains, jumps rope, goes to work for days straight, comes home, never gets sick, in an ICU intubated for about six to eight weeks, not able to communicate with us. And to be told that he may not make it can really hurt an individual. And that’s where I started to see that I am in a position where I can make a difference for people that are in his situation. …

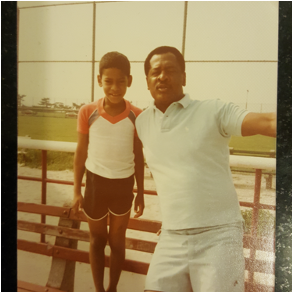

Dr. Carl Crawford Jr. with his father, circa 1983

And my dad, he hung on because he was a fighter. And he worked through cancer treatment, through radiation, through multiple surgeries, through compression fractures, and he kept going. And one of the things that I’ve always taken with me is, never quit no matter what, because he never quit.

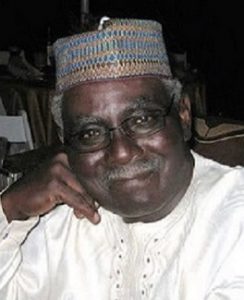

Dr. Iyasere: We suddenly lost my father in 2016. And it was very unexpected. And it took a lot of processing afterwards to understand what had happened in the hospital, and not to think that there had been something overlooked. And so even to this day, when we think about it, we do think about whether or not: Were there differences in the way my dad was approached and the way he was spoken to, or the care he received? And I think we’ve had a lot of time to reflect on it, but I think it still points out how important it is that we engage in the process with our patients [and their families], that we talk to our patients, that we think about how to best translate the language of medicine.

Solomon Iyasere

When I start to think about my role now at the Dalio Center for Health Justice, one of the things that very much propels me and what I do every day is thinking about my dad and thinking about his experience in the hospital and thinking about what could have been done differently for him. And unfortunately he is not with us today but it is that experience which has absolutely transformed the way I think about healthcare and the way I think about my role in healthcare and what I can do to eliminate gaps in care for our most vulnerable populations.

On the importance of communication

Dr. Iyasere: Being able to translate the language of medicine, not only into approachable language, but then also to share in that experience with your patients is so important and so meaningful. And I think it’s something that we all need to learn how to do, how to take some of the burden from our patients and share the experience with them.

Dr. Crawford: In this day and age, there’s so much information that it’s hard for anyone to sift through it. And there has to be people [who are] able to relay medicine and health [information] to people who are coming to us for that help…. I hope that patients that are out there know that they deserve everything from their caregivers and they should not accept care that they think is substandard. They shouldn’t be afraid if they don’t understand something to be able to ask a question.

On addressing vaccine hesitancy and gaining trust

Dr. Crawford: If my friends know that I got a vaccine and they were like, “Dr. Crawford, you got a vaccine?” And I would say, yeah, you give me two more shots if need be because I know that this is safe because my colleagues work on this and we all participate in this and we know that it’s safe. …. And I think we’re at this point where medicine has opened up their arms and said, we are offering our help. And now it’s just a matter of the population, our community to say, “Well, we accept your help.” And I think we just have to continue to open up our arms and continue to educate and use our platforms to reach as many people as possible.

Dr. Iyasere: This is the beginning of not rewriting history but reckoning with history and saying, we recognize why people don’t trust vaccines. We recognize why people feel uncomfortable and we will do whatever we can as a healthcare community to rebuild those bridges, to build the foundations of trust in our communities and to say, this is our safest way to make sure that we save lives in our country.

On building a foundation for the future

Dr. Crawford: As program director for our Gastroenterology Fellowship, I try to teach my trainees …. When there are patients in the hospital, advocate for your patients, treat them like your mother was in the hospital. If this patient’s not getting a procedure, is that the right thing to do? Would you let your mom hang out without getting a procedure if it was scheduled for this time, or at least communicate as to what the barriers are, but don’t let people stay in the dark, you have to be really engaged with everyone.

Dr. Iyasere: I think one of the most meaningful experiences I have had in recent memory, we did a pop-up vaccine site at Abyssinian Baptist Church and seeing so many people of color come in to be vaccinated, I was tearful. … It made me think like, OK, I’m not going to stop until we reach everybody. So I do see that change in how people are reflecting and thinking. And I think that the more that we can bring communities together, I think that not just for now, it’s not just about vaccination, that’s a huge part of it, but as I said, it’s really sowing seeds for the future.

Listen to the full episode.