Making Childbirth Safer for Moms

How Dr. Mary D’Alton is working to reduce maternal deaths and complications.

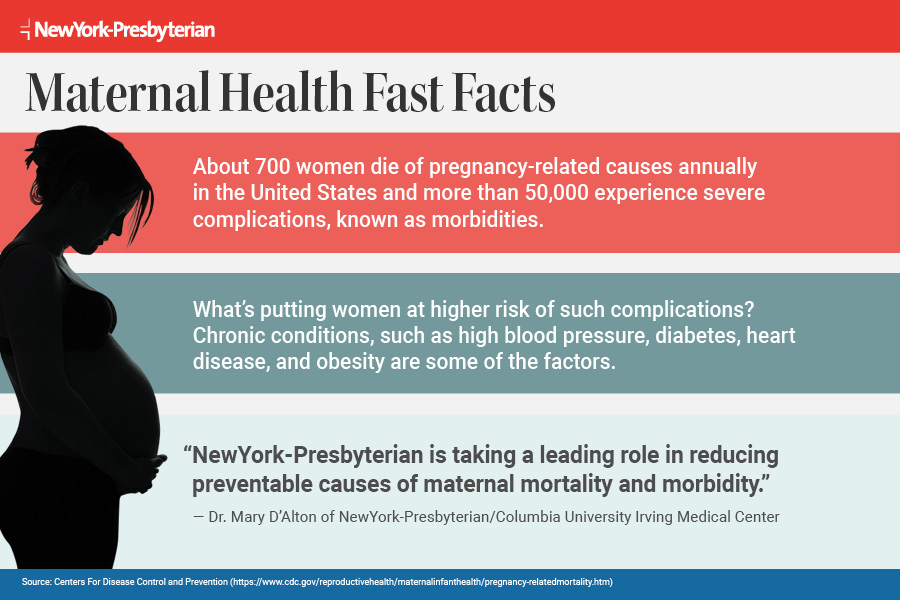

Every year in the United States, an estimated 700 women die from pregnancy or childbirth complications, and more than 50,000 experience severe complications, from shock to kidney failure.

And the problem is growing.

The rate of severe complications related to labor and delivery rose almost 200 percent from 1993–2014, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control.

And while maternal mortality has declined globally in recent years, several studies indicate it’s on the rise in the U.S. The maternal death rate increased by 27 percent from 2000-2014 for 48 states and Washington, D.C., according to an analysis published in the American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology. Among developed countries, the U.S. ranks last and also falls behind many poorer countries, such as Serbia and Vietnam.

What are the causes of maternal deaths in the U.S., and how can we prevent them and the rising tide of near misses? We spoke with Dr. Mary D’Alton, who is drawing national attention to the problem and working toward making pregnancy and childbirth safer.

As chair of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving Medical Center and director of services at NewYork-Presbyterian Sloane Hospital for Women, Dr. D’Alton specializes in high-risk pregnancies. She also serves as co-chair of the Safe Motherhood Initiative, which has implemented changes in New York State hospitals to reduce maternal deaths and serious complications. In 2018, NewYork-Presbyterian and Columbia University Irving Medical Center opened the Mothers Center, the nation’s first multidisciplinary center to focus specifically on caring for pregnant women with complex medical and surgical conditions.

Why aren’t maternal deaths going down in the United States?

The nature of women delivering children over the last 20 years has significantly changed. Number one, many pregnant women are older, and as women age they are more likely to have more complications medically and surgically. Obesity, which is on the rise, also increases risk in pregnancy, and women today are more likely to have chronic hypertension (high blood pressure) and diabetes.

Another factor we see in our center, thanks to medical and surgical advancements, is that women who have had organ transplants, have a history of cancer, or suffer from a chronic condition, such as cystic fibrosis or congenital heart disease, are becoming pregnant. These are women who previously were not considering pregnancy and are now becoming pregnant.

We also know that, nationally, non-Hispanic black women are three to four times more likely to experience a maternal death and considerably more likely to experience a severe complication. This is completely unacceptable, and we must address the factors that are driving these outcomes, including racism in our society and implicit bias in care.

Are life-threatening events a growing issue?

Serious maternal morbidity, meaning significant medical or surgical complications for the mother, is going up, and we have definitive data on that. I’m not talking about an increased hospital stay for a few extra days. I’m talking about very substantial maternal complications causing the mother to be admitted to an intensive care unit or requiring a hysterectomy, which will limit her future plans to become pregnant again. There’s an increase in incidences of very significant respiratory distress, cardiac events during pregnancy, strokes, severe renal (kidney) failure — complications that no one would argue about in terms of their serious nature. So we are not just focusing on maternal mortality. There’s an enormous need to reduce severe complications, as well.

What are the leading causes of preventable maternal deaths?

The most common are hemorrhage, which is significant loss of blood; hypertension, which can develop rapidly in pregnancy and cause bleeding in the brain; and venous thromboembolism, which is a blood clot in the lungs. A reasonable estimate is that 50 percent of maternal deaths in the U.S. are avoidable, which is why we’ve focused on making changes in clinical care that target these three causes.

“My goal was to create something unique here at NewYork-Presbyterian for the care and management of expectant mothers who have significant medical and surgical complications.”— Dr. Mary D’Alton

What key efforts are underway to reduce preventable maternal deaths?

Tremendous focus is being placed on what needs to be done to keep moms safe through initiatives like the National Partnership for Maternal Safety and the Council on Patient Safety in Women’s Health Care. Prior to 2013 or 2014, the majority of hospitals did not have standardized protocols for obstetric emergencies. Our first area was to try to standardize care at hospitals throughout the country, and I feel we have moved the needle on that. California has the led the way, and deaths have decreased significantly in the state because of standards in practices such as managing hemorrhage. We have also worked to increase fellowship training in maternal health, which includes obstetric emergency simulation drills, and to introduce uniform designations for levels of maternal care, which indicate a hospital’s capability to care for women with higher risk.

What’s happening in New York State to make childbirth safer for moms?

We have introduced three standardized approaches for treatment of maternal hemorrhage, hypertension, and venous thromboembolism. We focused on those three because they are leading preventable causes of maternal death and can happen in any patient at any time, even low-risk pregnancies. Through a combined effort called the Safe Motherhood Initiative, we drew up protocols in New York State for managing these three obstetric emergencies. Our goal was that we would have 75 percent of hospitals in New York State adopt these policies, and we are thrilled that we’ve surpassed that original goal; virtually all hospitals in New York State are in some phase of enacting these standardized protocols so that they are consistently followed in every patient at every time. Implementation of these protocols raises important questions, such as, is there a hemorrhage cart on the labor floor with all the medicines, instruments, and supplies needed to optimally treat a woman experiencing potentially life-threatening bleeding? In some situations, a woman’s risk may be so significant that we would recommend she not deliver in a smaller hospital but in a tertiary care hospital, where more resources are available.

Dr. Mary D’Alton

Have you seen results in New York State?

Our maternal mortality ranking has significantly improved. We were 48th in the nation when we started this effort in 2013, and we’re now 30th. Still, it’s not something that we’re very proud of because I and many of my colleagues believe that there is great care here in the majority of our hospitals in New York State and that standardization and regionalization of care — meaning getting the sickest mothers to the appropriate institution — will substantially improve outcomes.

What was your vision for the Mothers Center, which opened in the summer of 2018?

My goal was to create something unique here at NewYork-Presbyterian for the care and management of expectant mothers who have significant medical and surgical complications. It uses a multidisciplinary care model, leveraging the enormous talent that is here at NewYork-Presbyterian, including the heart center, the neurological institute and the cancer center. Patients are seen by specialists in the same location. If a pregnant woman has cardiac disease, she is seen in the same space by her maternal-fetal medicine physician and her cardiologist. It is the first of its kind in the country. Although many centers are focusing on certain conditions like diabetes or hypertension, I don’t know of a single center that focuses on all maternal conditions in the same space in such a collaborative way.

What’s the next big step?

I believe that the process of reviews is absolutely essential to helping us reduce maternal deaths. The U.K. has led the world in their analysis of maternal deaths. Since the 1950s, they have had a confidential inquiry into every single maternal death in the U.K. From that has come a publication every three years analyzing trends, and those trends and causes of maternal death are then fed back into practice patterns to improve care and outcomes for women. For instance, they noticed that there was a substantial number of deaths occurring from venous thromboembolism, so they put protocols in place for care that has now significantly reduced its incidence in the U.K. I’m delighted that New York State is committed to creating a Maternal Mortality Review Board to undertake comprehensive multidisciplinary reviews of maternal deaths. I am privileged to be involved in these efforts on both the state and city level. Reviews are critical to our effort in New York. They will help us determine if lessons can be learned from a maternal death and what changes need to be made where prevention is possible.

Learn more about the Mothers Center here.