‘I’m Proud of My Family’s Resilience and Perseverance’

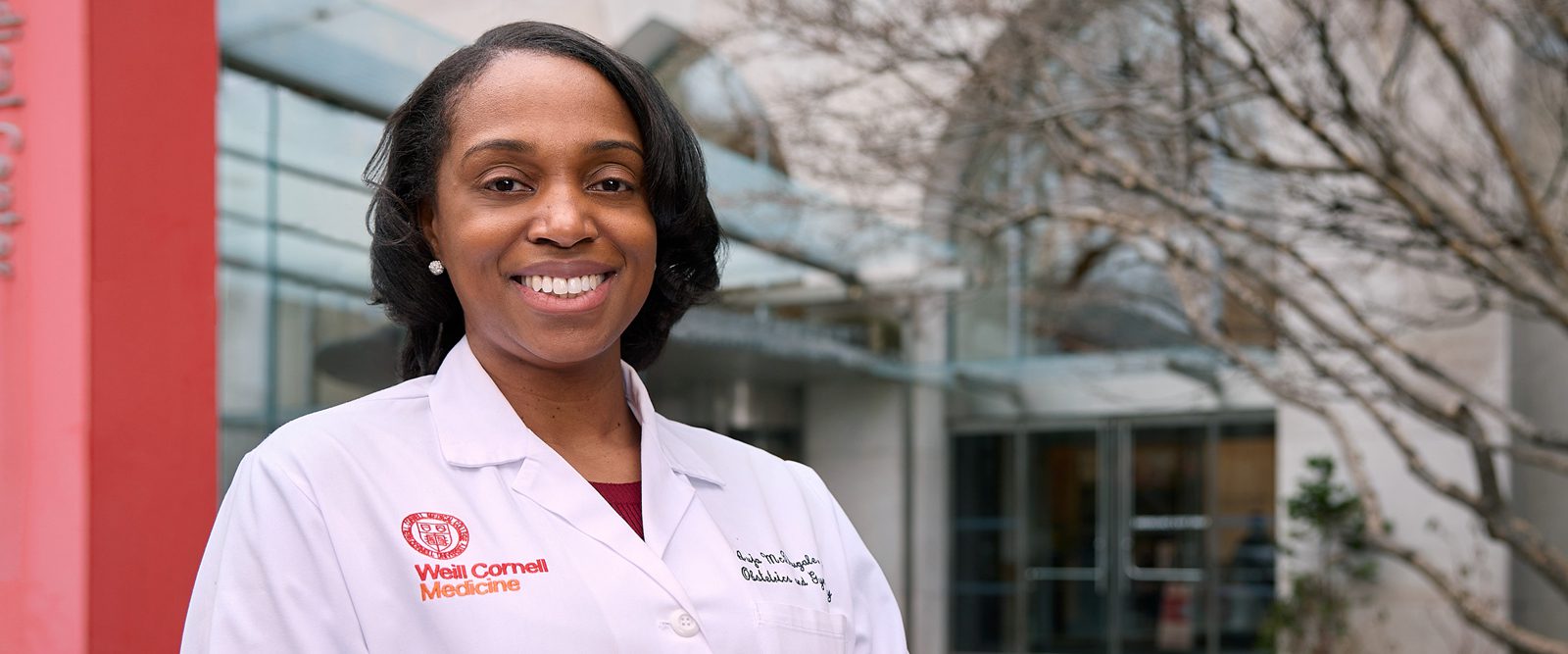

In honor of Black History Month, OB-GYN Dr. Auja McDougale shares how her family’s rich history shaped who she is today and inspires her to give back to her community.

My grandmother used to say to me, “Have something within.” Being a Black woman, there are quite a number of challenges and barriers “from without.” When you have “something within,” it is that inner voice that gives you the power, gives you the strength, and gives you the confidence to move forward.

As an OB-GYN at NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center, and an advocate for global and local health, I often think about my family’s influence on who I am today. I’m proud to represent their legacy of resilience and perseverance.

On my mother’s side of the family, my grandmother was the queen, to say the least. She was raised in the Pennsylvania Dutch Country by parents with a mixed background — my great-grandmother was light skinned, Native American and German, and my great-grandfather was a dark-skinned, tall, handsome Black man from Alabama. They were a part of the hardworking, Black middle class in the early 1900s.

My grandmother wanted to get an education, so she went to Tuskegee Institute in Alabama and got her Ph.D. in psychology in the late 1960s. While she was in college, she joined a student civil rights organization and participated in peaceful protests. She marched in Selma with Martin Luther King Jr., and what I remember most is that her stories were uplifting and about a sense of community and unity. Her experience really sparked our passion as a family to be activists and part of a forward movement.

Although she loved growing up Pennsylvania, she was excited to try the big city life, so she moved to New York City in the 1970s and started a private practice. That’s how our family eventually settled in southeast Queens, in the historic Addisleigh Park neighborhood which was also home to many famous Black Americans like Billie Holiday, Jackie Robinson, and W.E.B. Du Bois. She also became an ordained minister, and she was on staff at some local hospitals, one of which is now NewYork-Presbyterian Queens.

Dr. McDougale with a picture of her mother.

My mother was quite the academic. She went to Queens College and was first in her class with a degree in biology. She met my father there. He comes from a family of Southerners, from South Carolina and Georgia, and they ended up in Queens because of racial discrimination. He often talks about the bus rides down south during the summer to visit. Once they passed the Mason-Dixon line, he would have to get up from the front of the bus and walk to the back, to the colored section. And I always admired how his father would never miss a day to vote, even when he had terminal cancer and had to be carried up the stairs in his wheelchair by my father and uncle.

After college, my mother decided to go into the military. She was in the Army for quite some time, and then she came back home, raised me and worked as a postal worker. She unfortunately died very young, at the age of 38.

I was young when my mother passed away. I don’t have all the details which still is haunting for me. The hospital she died in no longer exists, but I remember how cold it felt. I always think, what if she had gone to another hospital? Would the experience have been different with more resources? She was young, beautiful, smart, and just really taken too soon.

A lot of people have similar stories, right? So, it certainly does impact how I look at the doctor-patient relationship and how I look at community health in general. It really reinforces my mission to provide access to care and pay attention to areas of need, as part of my work at NewYork-Presbyterian and Weill Cornell Medicine.

I am proud to be an avenue where voices of the Black community can be heard. We have to be mindful of how unconscious racial biases can influence how Black people perceive health care. I think if we look at people in a humanistic way, we’ll be able to overcome some of those barriers. That’s why having a direct partnership with communities is so important. The programs I’m a part of here, specifically around doulas, community health workers, mobile health units, paying attention to the social determinants of health, mentoring young students of color — it all helps.

I often hear my grandmother’s voice when we talk about things like health equity, diversity and inclusion, local health, global health — it’s a collaborative effort. And that resonates, because my grandmother was very much out in the community. She preached, she sang, she taught, she did everything. She was determined to follow her own path. And I’m just so appreciative that she did that, that she broke the mold.

This Black History Month, I want to recognize how Black people have persisted and are thriving. It’s a time to be full of pride and recognize how people have moved forward. And what I really love to hear about are the everyday lives — that’s what we really need to celebrate. I’m raising a son, a little Black boy, and I want to teach him about his ancestors and share our family stories with him.

I remember the first time I delivered a baby. I was living with my father’s brother in Miami, Florida, where I did my residency. And my uncle, he was just so proud. He used to count how many deliveries I’d do, and even years later, he’d ask me, “So what’s your number now?” And I’d say, ‘Man, Uncle Earl, I stopped counting. And now I teach others how to do it.”

He passed away a few years ago, and now I think back about how wonderful it is that I had the opportunity to come full circle, to respect the legacy of so many who have come before me, and now be able to help thousands of people at the beginning of life.

Additional Resources

Find out more about these community initiatives:

Learn more about NewYork-Presbyterian’s work to improve health equity through the Dalio Center for Health Justice.