How to Protect Your Brain Health During Menopause

A leading expert explains how declining hormones at menopause impact the brain, and what you can do to improve your brain health and lower the risk for Alzheimer’s disease.

Many women know that the transition into menopause means a change in menstrual cycles and ovarian function, but what about the changes to the brain during this phase?

“We associate menopause with the ovaries, but when women say that they’re having hot flashes, night sweats, insomnia, memory lapses, depression, anxiety, those symptoms don’t start in the ovaries,” says Lisa Mosconi, Ph.D., director of the Alzheimer’s Prevention Program and the Women’s Brain Initiative at Weill Cornell Medicine and NewYork-Presbyterian. “They start in the brain. Those are neurological symptoms. We’re just not used to thinking about them as such.”

Dr. Lisa Mosconi

One reason why menopause impacts the brain is because estrogen, the main female hormone, is involved not only with reproduction but also with brain function. When estrogen levels start fluctuating widely during perimenopause, the two- to seven-year period preceding menopause, and then drop after menopause, there are significant effects in the brain. For more than 15 years, Dr. Mosconi has studied what happens when estrogen begins to fall and how to support and protect the brain as you age.

How Menopause Impacts the Brain

Hot flashes

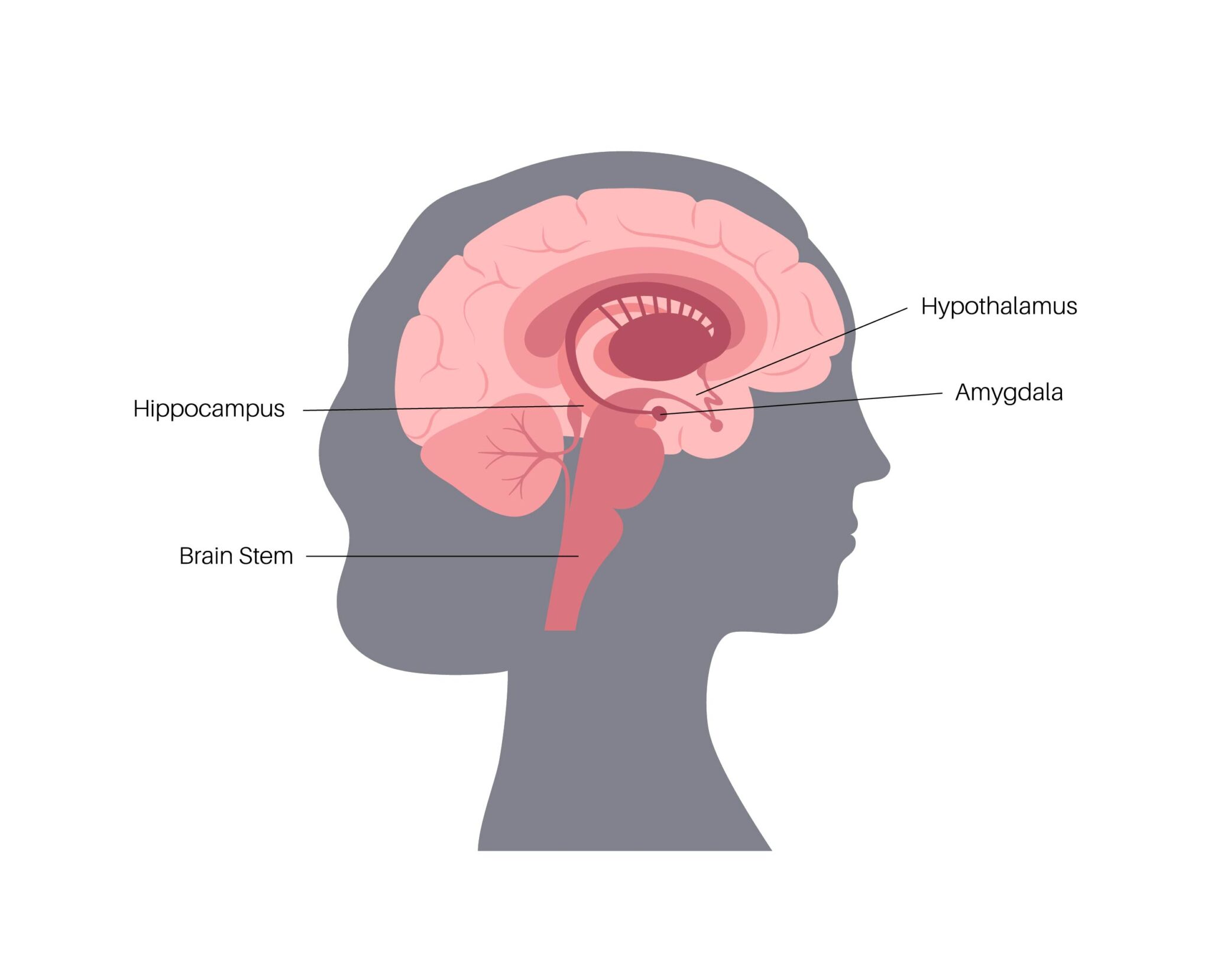

Hot flashes, which are very common in perimenopause, are associated with the function of the hypothalamus, the brain region in charge of regulating body temperature, says Dr. Mosconi. “When estrogen doesn’t activate the hypothalamus correctly, the brain cannot regulate body temperature correctly.” Hot flashes and night sweats may occur as a result.

Sleep problems

A similar change happens in the brain stem, the control center for the body’s sleep and wake cycles, she says. “When estrogen doesn’t activate the brain stem correctly, we have trouble sleeping and sleep patterns change.”

Mood changes

Other perimenopause-related effects can be tied to the amygdala, the emotional center of the brain, she says. Waning estrogen here can contribute to mood swings, depression, or anxiety.

Forgetfulness

Changes also occur in the hippocampus, the brain’s main memory center. “When estrogen levels ebb in this region, we may feel forgetful,” says Dr. Mosconi.

Brain fog

Many people experience fuzzy thinking during perimenopause. “So many women worry that they might be losing their minds at menopause,” says Dr. Mosconi. “But the truth is that your brain is going through a transition and needs time and support to adjust.”

Fortunately, the brain changes brought on during perimenopause appear to be temporary and do not affect cognitive performance, according to Dr. Mosconi’s research. “Women may be tired, but we are just as sharp.”

Alzheimer’s disease

For some women, the withdrawal of estrogen in perimenopause can have a more serious effect, setting the stage for Alzheimer’s disease later in life, says Dr. Mosconi. Her research has sought to explain why women are more likely than men to develop the devastating disease. “Alzheimer’s affects close to 6 million people in the United States,” she says. “But almost two-thirds of those people are women.”

Women live longer than men overall, giving them more time to develop Alzheimer’s, says Dr. Mosconi. But the gender longevity gap doesn’t fully explain the disparity.

Her research offers clues. “Estrogen literally pushes neurons to burn glucose to make energy. If your estrogen is high, your brain energy is high,” says Dr. Mosconi. “When your estrogen declines, though, your neurons start slowing down and age faster. And studies have shown that this process can lead to the formation of amyloid plaques, which are a hallmark of Alzheimer’s disease.”

Brain scans show that while amyloid plaques are rare in men at midlife, women begin to see an increase during the transition to menopause, typically in their 40s and early 50s. “Many studies show that Alzheimer’s starts with negative changes in the brain years prior to clinical symptoms,” she says. “For women, it looks like this process starts during the menopause transition.”

Dr. Mosconi emphasizes that not all women develop the plaques, and not all women with the plaques develop dementia. Rather, perimenopause appears to activate the accumulation of plaques, at least in women who have a genetic predisposition for Alzheimer’s, such as those who have a first-degree family member with the disease or who carry a particular gene (called APOE4), she says.

Women who have both ovaries surgically removed, which causes an abrupt drop in hormones, may fare even less well than those who go through the menopause transition, Dr. Mosconi says. “Unfortunately, there is evidence that having the uterus and, more so, the ovaries removed prior to menopause correlates with a higher risk of dementia in women,” she says. But the risk drops if they start taking hormones soon after surgery and continue treatment until the natural age of menopause, she adds.

How to Protect Your Brain

The good news is there are multiple ways to improve your brain health and lower your chances for Alzheimer’s disease and other forms of dementia. “This includes a variety of factors, from diet and exercise to sleep, stress reduction, and reduced exposure to toxins, including chemicals found in things like plastics and pesticides,” Dr. Mosconi says.

Here’s a closer look at what you can do to improve your brain health:

Diet

The Mediterranean diet seems to work best for slowing brain aging. “By doing brain scans, we have shown that the brain of a 60-year-old woman on the Mediterranean diet looks five years younger than that of a 50-year-old woman on the Western diet,” Dr. Mosconi says. (The eating pattern features an abundance of fruits and vegetables, nuts, seeds, fish, and olive oil.)

Dr. Mosconi also touts disease-fighting antioxidants in foods like berries — particularly goji berries and blackberries— and citrus foods for promoting a healthier brain. Even espresso, in moderation, is helpful. “It has the highest antioxidant power of all beverages,” she says.

Exercise

Physical activity helps both men and women prevent dementia. But it seems to be of greater benefit for women, says Dr. Mosconi.

Exercise also helps to lower stress, another barrier to good brain health. “Brain imaging studies are showing that women’s brains are actually more vulnerable to chronic stress than men’s brains.” Meditation or yoga also can lower stress.

“These lifestyle changes are known to promote brain health overall, reduce the risk of dementia later in life, and lower the risks and complications of so many additional health issues to boot,” says Dr. Mosconi. “It’s a win-win.”

Additional Resources

Learn more about women’s health at NewYork-Presbyterian.

Lisa Mosconi, Ph.D., is director of the Alzheimer’s Prevention Program, including the Women’s Brain Initiative and the Alzheimer’s Prevention Clinic, at Weill Cornell Medicine and NewYork-Presbyterian. She is also an associate professor of neuroscience in neurology and in radiology at Weill Cornell Medicine. Dr. Mosconi’s research is focused on the early detection and prevention of cognitive aging and Alzheimer’s disease in at-risk individuals, especially women, and she has published more than 150 papers in medical journals. She is author of The Menopause Brain, and The XX Brain: The Groundbreaking Science Empowering Women to Maximize Cognitive Health and Prevent Alzheimer’s Disease and Brain Food.