Which Activities Are Safer During the Pandemic?

Public health expert Dr. Ashwin Vasan breaks down the coronavirus risks and the precautions to take this summer.

After several months of social distancing and sheltering in place to help slow the spread of COVID-19, people are eager to resume aspects of normal life, especially with the arrival of summer. Businesses are reopening. City streets and beaches are becoming more crowded. Travel is picking up again. While life won’t be the same as before the outbreak, there is a way to get back to some normalcy while staying safe. It begins with weighing the coronavirus risks and knowing which activities are safe during the pandemic.

Public health expert Dr. Ashwin Vasan, an assistant attending physician in the Department of Medicine at NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving Medical Center and an assistant professor at the Mailman School of Public Health and Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons, talked to Health Matters about how people can minimize risk and prioritize safety.

Dr. Ashwin Vasan

Many people are experiencing quarantine fatigue, the losing of tolerance for being isolated and staying indoors. Why is it important to be mindful of quarantine fatigue?

Anyone can lock themselves down for a couple of weeks or even a couple of months. But now we’re moving beyond three months and it’s starting to get too hard. The all-or-nothing approach in this epidemic response is causing people to lose patience with their situation and to focus on the wrong things.

We are, at our very basic nature, social creatures. Studies of social isolation have shown that it has serious long-term effects on both our mental and physical health. So, because we’re being forced to conduct our lives in dramatically different ways, we’re losing our tolerance for being forced to be separate from other people.

We can compare this all-or-nothing quarantine approach to the abstinence-only message of HIV prevention: Data shows that it doesn’t work. It’s not sustainable. Instead, we need a harm-reduction approach. One that says, “Look, you’re going to go outside; you might have trouble distancing from other people. You might not always follow the rules perfectly, but you can try to socialize in the safest ways possible.” It’s up to the experts and government officials to show the public how the safe choices (face coverings, handwashing, social distancing) are also the easy choices.

What are the best ways to stay safe?

If you’re going to engage in activities, whether they’re considered higher risk (like riding in the subway) or low risk (like walking outside), there’s a way to do so while being safe. And those are simple: Wear a mask correctly, wear a face shield in more crowded areas, avoid large groups (and having long conversations in close proximity), stay 6 feet apart from as many people as possible, and wash your hands regularly. These are things we can all do to minimize our risk.

Which activities are safer during the pandemic?

Studies are showing that the bulk of transmission is happening in enclosed spaces, indoors in office buildings, public transportation, and within households. Outdoor settings with adequate ventilation are much safer. There is up to 80% less transmission of the virus happening outdoors versus indoors. (One study found that of 318 outbreaks that accounted for 1,245 confirmed cases in China, only one outbreak occurred outdoors.) That’s significant. I recommend socializing or spending time with others outside. We’re not talking about going to a sporting event or a concert or the pool. We’re talking about going for a walk or going to the park, or even having a conversation at a safe distance with someone outside — these are all activities that are far less risky.

What are some high-risk activities that should be avoided if possible?

Riding the subway during peak hours, large gatherings and crowds, prolonged exposure to people indoors. Also, try to minimize trips to the grocery store, bank, or post office. Those are high-risk activities, if not done safely. Think about staggering those errands or doing bigger shops less often instead of multiple times a week.

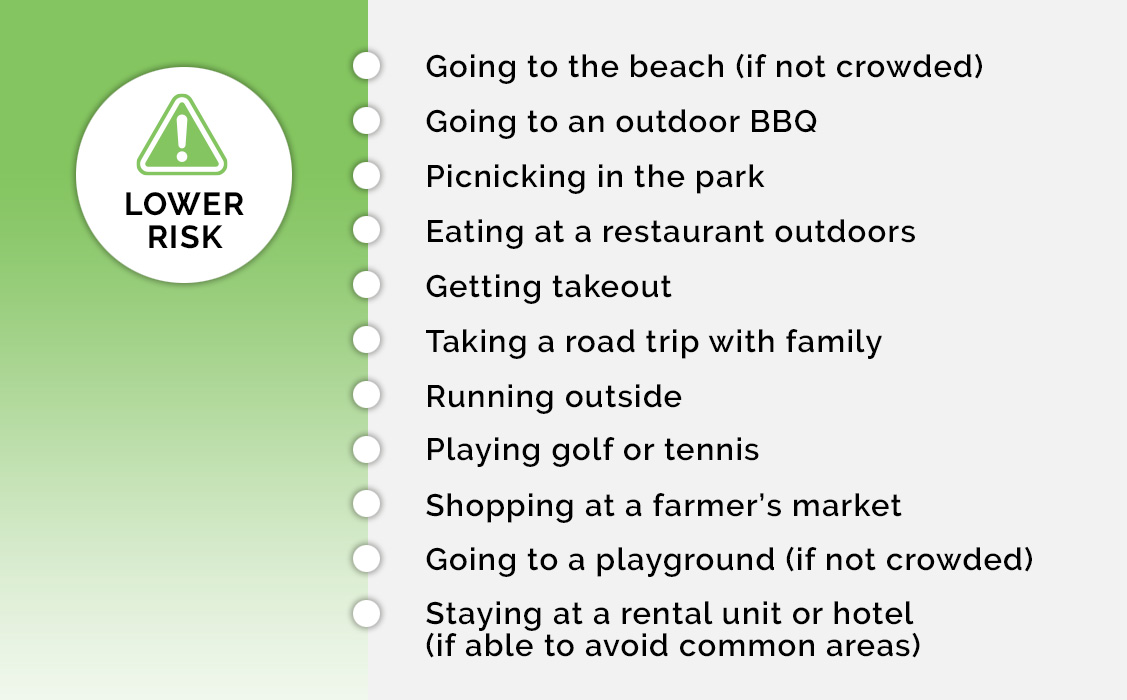

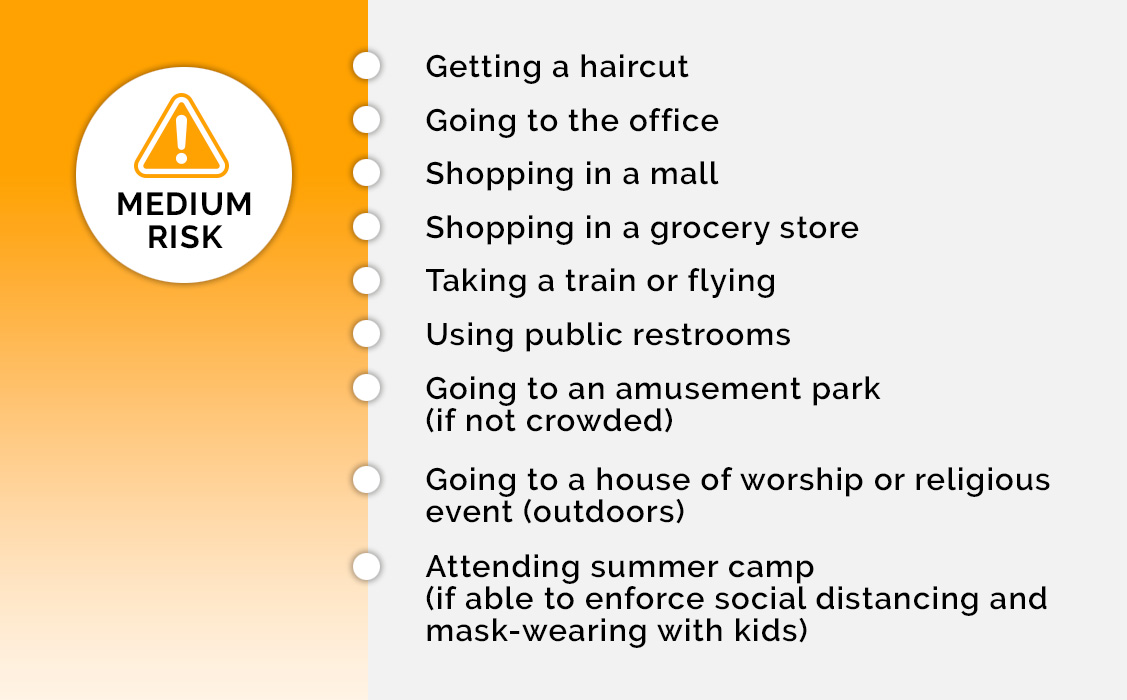

How Safe is It?

Dr. Ashwin Vasan of NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving Medical Center ranks activities by risk level of contracting COVID-19.

There’s talk of forming “pandemic pods” and “quarantine buddies,” but is this safe?

If people want to get together, it’s important to do so carefully. I advise keeping it small: one family to another family, or only close relatives. The next thing I recommend is for everyone to get tested beforehand — COVID-19 testing is more widely available now.

The other approach is quarantining for about 14 days, then opening yourselves up to each other, to ensure no one is sick. However, if you do it, just be sure to communicate with one another on how you’re approaching this to make sure you’re all on the same page.

Apart from physical health, how is quarantine fatigue affecting our mental health?

Quarantine fatigue is real and it’s totally understandable. This is hard. This is not easy for anybody and it’s even harder for people who face social and health challenges. No one should feel bad, beat themselves up, or judge anyone else for feeling quarantine fatigue. And so, it’s vital that we take care of ourselves by exercising, eating healthy, keeping in close contact as much as possible with loved ones through digital media, and fostering your relationships — those things are really important.

In order to combat quarantine fatigue, get outside, but do so safely. Remember, it’s all about a sustainable, harm-reduction approach. Make sure you’re masked up and you’re observing the right distancing guidelines, but do get outside. Don’t let it prevent you from seeing anybody or interacting with anybody, if you can do so safely. Minimizing your risk doesn’t have to mean eliminating socialization altogether. By acting with caution and knowing which activities are safe during the pandemic, you can get back out there and enjoy life.

Ashwin Vasan, M.D., Ph.D., is an assistant attending physician in the Department of Medicine at NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving Medical Center and an assistant professor of clinical population and family health and medicine at the Mailman School of Public Health and Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons. He is also the chief executive officer of the mental health nonprofit Fountain House, one of the world’s oldest and largest community-based mental health and public health charities, serving more than 100,000 people living with mental illness across the world.