How One Young Woman’s Determination to Find a Cure for Her Epileptic Seizures Led to Her Living Seizure-Free

Gianna Spirio and her doctors refused to give up as they searched for a treatment to stop her chronic and debilitating seizures. At 25, she is now living the life of independence she always wanted.

In many ways Gianna Spirio is your average 25-year-old. She loves long drives by herself, blasting her favorite music and singing along as loud as she wants. She enjoys alone time at the mall shopping for shoes and clothes and going to the beach and her favorite taco place solo.

Though Gianna has lots of friends and family who would be happy to join her, these independent experiences are especially meaningful for her. After a lifetime of debilitating seizures due to epilepsy, a neurological condition that causes a disruption in the electrical network of a person’s brain, Gianna is now two years seizure-free and, unlike the average 25-year-old, is experiencing autonomy for the first time. In the past, she needed a chaperone in case of medical emergencies.

“I finally have my independence,” she says. “I thought I wasn’t a fan of shopping. It turns out I love the mall. I love shopping. But I like it when I can do it by myself, when I can choose what I want to do when I want to do it.”

Living Life With Seizures

Diagnosed with epilepsy when she was two years old, Gianna had spent her life dealing with a neurological illness invisible to most people, but disruptive to her daily life. She was noise sensitive, meaning her seizures were mostly triggered by something like a loud car driving by, but they could also be triggered by anything that threw off the equilibrium of her body. Sometimes she would have a grand mal seizure, where she would have full body convulsions, while other times she would experience an absence seizure, where she would stare off blankly for a few minutes. Often, she was conscious during a seizure but unable to speak, or when she did the words would come out as gibberish.

“When you have something that people can’t see with the naked eye, it doesn’t exist to them,” she says, explaining how this led to disbelief and even bullying from her classmates, even into college.

Dr. Cigdem Akman

Gianna had been prescribed various medications through her adolescent years, but nothing could stop her seizures. In her early teens, she was referred to Dr. Cigdem Akman, former chief of Child Neurology and the current director of the Pediatric Epilepsy program at NewYork-Presbyterian Morgan Stanley Children’s Hospital. Dr. Akman recommended a comprehensive evaluation for Gianna to understand where her seizures were coming from in the brain and see whether a surgical intervention could help control them. After observing Gianna’s seizures and reviewing electroencephalogram (EEG) recordings, where electrodes are attached to the scalp to measure electrical activity in the brain, Dr. Akman and her team hypothesized that the seizures were coming from the left side of Gianna’s brain, most likely from her frontal lobe. However, her brain imaging studies did not show any lesions or subtle abnormalities in this area.

To confirm this, Dr. Akman and neurosurgeons Dr. Guy McKhann and Dr. Neil Feldstein of NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving Medical Center suggested intracranial EEG monitoring, where a portion of the skull is removed so that electrodes can be attached on the surface of the brain to get an even clearer picture of the source of the seizures. If they could pinpoint the area where the seizures were originating, they could potentially remove that portion of her brain to stop her seizures. Unfortunately, the intracranial EEG results showed that her seizure focus was overlapping with the area assigned to motor function of her right leg, therefore the surgical team believed that surgery on the frontal lobe was too risky.

Despite her condition, Gianna was a star athlete who had dreams of playing collegiate level soccer, and everyone agreed that the best path forward would be to focus on medication treatment.

“Maybe new treatment modalities or surgical innovations would emerge,” Dr. Akman recalls telling Gianna and her family. “Technology is advancing, and I told them we could revisit the alternative treatment options for her in the future.”

On the college soccer team, Gianna continued to have seizures, causing social stress, and making her increasingly nervous to spend time in public or around new people.

“Sometimes I would cry because I had another seizure,” she says. “Maybe I had a good week where I didn’t have any seizures and then I’d have one in front of people I just met. I thought it’s going to scare them, it’s embarrassing. I didn’t know what they were going to think of me. It was hard.”

Refusing to Give Up Hope

Driven by a passion to be seizure-free, Gianna and her family were eager to try new technologies as they emerged. In December 2018, just after she had graduated from college, they agreed to try a new, less invasive kind of intracranial EEG called stereoelectroencephalography, or SEEG to explore the area possibly causing her seizures. In this procedure, the bone is penetrated with holes only 2mm in size to put in small electrodes in the areas of her frontal lobe that were suspected of causing her seizures as well as areas deeper in the brain, including the insula and the cingulate gyrus.

“With the new technology we hoped we could localize the seizure focus that was situated below the surface and get a better understanding of the connections between the neighboring regions than we could before,” explains Dr. Akman.

Dr. Guy McKhann

The advanced technology found a critical piece of information that would ultimately lead to a turning point for Gianna: the seizures were coming from the insula, a region deep in the brain covered by 3 lobes that acts as a major communications hub. Imprecisions in surgery in that area of the brain, which is surrounded by what Dr. McKhann calls a “picket fence of arteries,” could lead to stroke or impair Gianna’s language abilities.

Around that time, a new device had been approved for the treatment of epilepsy called a Responsive Neurostimulator (RNS). With this device, two electrodes are inserted into or on the surface of the brain that can record, predict, and stimulate the neurons to stop the seizures. Everyone agreed that RNS would be the safest option for her. Electrodes were placed within Gianna’s insula, but she developed side effects with the stimulation that prevented it’s optimal use. After two years, the RNS was removed.

"I knew there was a light at the end of the tunnel, and I’m just so grateful that my doctors at NewYork-Presbyterian never gave up."— Gianna Spirio

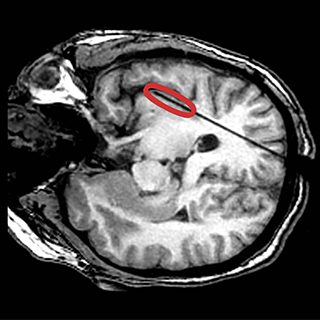

Gianna underwent a second SEEG in 2021. This time her doctors were able to pinpoint exactly where in the insula the seizures were coming from. Armed with this new information, Dr. Akman, Dr. McKhann and Dr. Feldstein believed that laser ablation, where small fibers are inserted through the skull to heat up and precisely destroy areas of the brain, might be a possible and less invasive option. The neurosurgical team had used laser ablation before, but never on the insula.

“We were confident with the technology that if we were conservative, we could do laser ablation in her insula safely,” says Dr. McKhann. “And if we could do it safely, that was Gianna’s best chance of stopping her seizures. Really her only chance.”

In June of 2021, a team of surgeons inserted tiny fibers into Gianna’s insula to use the laser heat to destroy the precise locations causing her seizures. Following the procedure, everyone was cautiously optimistic that Gianna’s seizures were finally under control. She suffered one seizure shortly after the procedure, which was different than her usual seizures — and it turned out to be her last one.

A laser fiber going through Gianna's brain and into her insula (circled in red)."

“It was a long journey for Gianna, and there was a big learning curve for all of us, both on the clinical side and for Gianna and her family,” says Dr. Akman. “If she or her parents didn’t trust us, if we didn’t have a good team, and if we as doctors weren’t open to the application of new technologies and new ideas, I don’t know if this outcome would have been accomplished.”

Dr. McKhann notes that it took Gianna’s extraordinary mental strength, determination, and willingness to try the latest technologies to finally find a cure for her epilepsy. “Most people wouldn’t have the fortitude to go through all of these procedures because they would get disappointed,” says Dr. McKhann. “And not just her, but her family, too.”

Gianna says her life has been about proving that nothing was going to hold her back. If someone suggested she couldn’t play college sports or that she wouldn’t graduate on time because of her seizures, her response was simply “Yeah, watch me.”

“I knew there was a light at the end of the tunnel, and I’m just so grateful that my doctors at NewYork-Presbyterian never gave up,” she says. “I feel like I’ve reached that light.”

Big Plans for the Future

A few months after her procedure, Gianna began working for Habitat for Humanity, building homes on Long Island. Her responsibilities were limited due to her epilepsy, but after one year being seizure free, she was allowed to do something she never thought she’d be able to do.

“It’s so bizarre, but the thing that made me happiest when I was one year seizure free was they let me use a nail gun when we were building houses,” says Gianna. “Before that I could only use a hammer or carry equipment, and I felt a little useless. But at one year they let me use power tools. Now I could build a frame for a wall in five minutes instead of one hour.”

Today, Gianna is finishing up a master’s degree in education, following her passion of working with special needs children. Building on her own experiences, she’d like to open her own school one day for children with disabilities. And she is planning to move into her own apartment, where she can’t wait to cook.

“My seizures were triggered by loud sounds, so if my mom was cooking and she needed to turn something electric on, she would warn me and I’d have to go upstairs,” says Gianna. “But the best part has been I’ve been the loudest in the kitchen. I’m using the blender now. I’m using the mixer. I’ll do it at the same time. And I know that I’m not going to have a seizure. And that makes me so happy.”