How an ICU Nurse Practitioner Helped Families Support Their Loved Ones From a Distance During the Pandemic

When the coronavirus outbreak prevented family members from being by their loved one’s bedside, a nurse found a way to let them be present and for staff to personalize patient care.

Mothers and daughters, left to right: Maureen and Caitrin O’Meara; Cynthia Schemel and Lisette Dalmau; and Nikki Lofton and Virginia Flintall.

One night in mid-April, Sondra Walter, a cardiac nurse practitioner, was sitting in the intensive care unit at NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving Medical Center, listening only to the hum of machines. It was not just quiet — it was too quiet.

“It was a surreal moment, unlike anything I’ve experienced as a nurse,” says Sondra. “It was silent, which is unheard of in the ICU.”

The ICU had doubled in capacity. Yet all the patients were sedated, and visitors were not allowed due to government restrictions designed to prevent the spread of COVID-19. Without a way to communicate directly with patients and with no family members at the bedside to offer information, Sondra, like so many other healthcare workers, longed for a way to connect with the patients under her care.

The profound silence gave way to a powerful solution: Sondra started asking family members to send in photos and stories about each patient in her unit. She then affixed the photos and messages from families to the handles of disposable lunch bags from the hospital and hung them by patients’ beds or outside their rooms so all the hospital teams could learn more about who they were caring for.

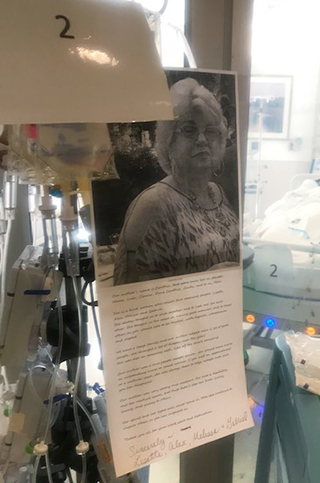

A photo and biography about Cynthia Schemel, shared by her family so that nurse practitioner Sondra Walter could hang it at her bedside.

“The families really took hold of this. We got such beautiful collages of photos and funny stories,” she says. “I thought by putting up pictures and letting the care team know how much their families cared for them, it could create a little more intimacy.”

“You’re grasping at straws just to feel like you’re there,” says Caitrin O’Meara, whose mother, Maureen O’Meara, was hospitalized in Sondra’s unit for more than a month and is now at home recovering. “It was just so comforting knowing there was somebody considering how we felt and thinking of us.”

People within the hospital were also moved by Sondra’s work. “After reading the cards, instantaneously these patients became the people that they were before they were sick. It was powerful,” says Dr. Gregg Rosner, a cardiologist who works in the ICU with Sondra.

“One of the devastating things about COVID is that, unlike any other disease we’ve ever dealt with in healthcare, it essentially excluded all visitors and family members from the hospital,” Dr. Rosner adds. “Sondra’s project gave the patients and their family members a voice.”

As Sondra hoped, her project also helped the staff get to know their patients on a deeper level.

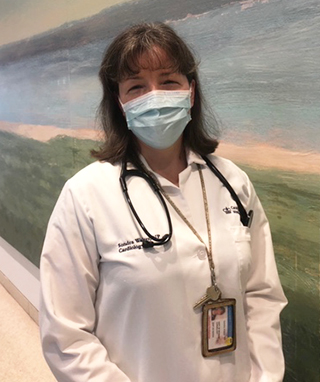

Nurse practitioner Sondra Walter at work at NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving Medical Center.

Through her work, hospital staff learned about the patients’ hobbies, their likes and dislikes, and their accomplishments in life. They would then incorporate these intimate details to deliver more personalized care.

When the team learned one patient loved playing the lottery, they purchased some scratch-off tickets as the patient was regaining consciousness to help encourage her recovery. An environmental services worker read one bio about a patient who loved calypso music and brought some in to play for them.

The photos and biographies shared by families allowed Sondra and her team to “bring back the nursing we all know how to do but was stripped away by this virus,” she says.

Comfort for Family Members

Sondra’s project proved to be a lifeline for Nikki Lofton, whose mother, Dr. Virginia Flintall, was hospitalized with COVID-19 for a little more than a week.

“It was so hard when she was sick. I wanted to be there, I wanted to be able to hold her hand and look at the doctors. It was heartbreaking,” says Nikki. “Sondra gave me something that I could do for my mom.”

Dr. Virginia Flintall (lower right) with her family.

Nikki shared that her mother, Virginia, was born at what is now NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving Medical Center in 1943 and earned her doctorate at Teachers College, Columbia University. She then worked as a consulting psychologist for Head Start in New York City, counseling young children from low-income families as they prepared for school.

Over the years, Virginia not only used her voice to support the civil rights movement, but also for her daughter. “She’s always been my fiercest advocate,” says Nikki. “My mother has always been there for me.”

With Sondra’s help, Nikki was able to do the same for her mother. As part of the collage she created, Nikki included the symbol for Alpha Kappa Alpha Sorority, Inc., which Virginia joined in 1963 during her college years. Virginia served five years as local graduate chapter president in early 2000 and Nikki followed in her footsteps to join and serve as local president as well.

Virginia Flintall’s sorority symbol, the Leaf Insignia, was hung by her bedside.

“I thought maybe one of my sorors might be working there, and they’d say a little prayer when they walked past the room,” says Nikki.

Sadly, Virginia lost her battle with COVID on April 22, 2020. But in her final days, Nikki says that her mother received an extra dose of “the human side of medicine.”

“The time Sondra took to humanize my mother by posting pictures, her story, and our sorority symbol meant the world to me,” says Nikki. “I know my mom would have truly appreciated the effort and love she took in doing so as well.”

Creating Connections

For Maureen O’Meara, a personal detail helped push her to get better after more than a month in the ICU. When Maureen started to regain consciousness, she was confused about where she was so the nurses talked about her daughter Caitrin’s upcoming wedding to calm and center her.

Then during her recovery, the team consistently discussed what Maureen should wear as the mother of the bride, because “we wanted to give her something to fight for,” says Sondra.

Caitrin O’Meara celebrated her wedding in August with her mother, Maureen O’Meara, by her side.

Sharing Maureen’s story also gave her family something to hang on to during a difficult time. “The day Sondra sent me a picture of it on the door was one of the better days, knowing that there was something there from us and that they could read about her,” says Caitrin, who celebrated her big day with Maureen by her side in August. “I can’t praise the staff enough.”

And in a patient’s final days, the smallest details made the biggest difference.

Lisette Dalmau wrote that her mom, Cynthia Schemel, was “a true people person” and “very strong and resilient.”

As a mom to four and a grandmother to 15, Cynthia “was a great cook,” says Lisette. “She would make rice pudding not just for her family who lived in the building, but all her neighbors. She and my son would cook together, and I called it their ‘happy land.’”

Though the family wasn’t able to be by Cynthia’s side when she passed away in April, they found comfort knowing that Sondra was there in their stead. In her final moments, Sondra played Cynthia’s favorite song and held her hand.

Cynthia Schemel (center) with her children.

“Sondra asking us to take part in this project made it so much easier for us to cope,” says Lisette. “She could see and feel what our mom meant to us and how heartbreaking this whole situation was.”

Sondra says the outpouring of gratitude from families for her efforts has been humbling. When people in New York City were cheering for essential workers every night at 7, she says she was quietly cheering for her patients’ families.

“I cannot imagine being separated from a family member when they are ill,” she says. “I consider it a privilege to be able to help a family or patient, and I was overwhelmed by the gratitude the families showed toward the medical staff for the care of their loved ones. It’s gratifying to feel like you are making a difference.”