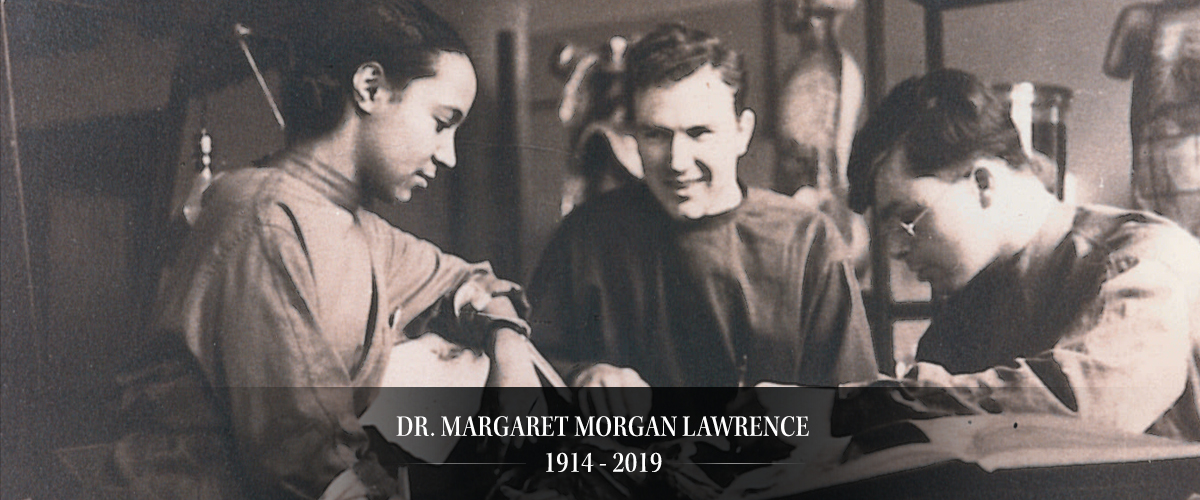

It Happened Here: Dr. Margaret Morgan Lawrence

How the country's first African American female psychoanalyst overcame adversity to become an expert on children's mental health disorders.

Every time she was turned away, Dr. Margaret Morgan Lawrence, whose career began at NewYork-Presbyterian in the 1940s, found a new opportunity to succeed, eventually becoming the first African American female psychoanalyst in the United States and the first Black female physician certified by the American Board of Pediatrics. Throughout her career, she was devoted to the underserved and developed pioneering programs in child psychotherapy in schools, day care centers, and clinics, and innovative methods that are still used by clinicians today.

“[My mother is] an extraordinary woman and trailblazing physician who in her career — first as a pediatrician, then as a child psychiatrist and psychoanalyst — faced the virulent barriers of racism and sexism with a deft blend of grit and grace,” wrote her daughter, Sara Lawrence-Lightfoot, in The Wall Street Journal in 2015. Lawrence-Lightfoot chronicled her mother’s journey in a biography the two collaborated on, Balm in Gilead: Journey of a Healer, published in 1988.

Early Days

Dr. Lawrence was born in 1914 in New York City and grew up in Vicksburg, Mississippi, the daughter of an Episcopal priest and a schoolteacher. Experiences in childhood led her to become interested in medicine at a young age: Her older brother died before his first birthday, from a congenital condition, leaving a sadness over the household that never went away, as described in Balm in Gilead. She grew up wanting to be a doctor in order to save a child like her brother and prevent her parents’ sadness. Her mother suffered from episodes of depression, going to bed and remaining there for weeks. Dr. Lawrence wanted to be a healer, and also mused to her daughter that the interest may have had to do with her father’s preaching and her witnessing spiritual healing as a child.

At 14, she moved to Harlem to live with her aunts, where she felt she could get a better education. She was admitted to the selective Wadleigh High, a public exam school for girls that would more adequately prepare her for college and a medical career. Here, she excelled, graduating with top prizes in Greek and Latin and a full academic scholarship to Cornell University.

In 1932, she arrived in Ithaca as the only Black undergraduate on Cornell’s campus, where she was not permitted to live in the dormitories. Instead, she lived in the home of a white family where she performed chores in exchange for a room in the attic. According to her daughter’s Wall Street Journal essay, Dr. Lawrence “worked as a maid in the homes of faculty members, often serving them breakfast before she went off to class, and returning at lunchtime to change into her maid’s uniform before going back to campus for the afternoon.”

As her senior year at Cornell concluded, Dr. Lawrence had a nearly perfect academic record and fully expected to be accepted by Cornell’s School of Medicine. She was shocked when she was denied. She later recounted being told by the dean, “Twenty-five years ago there was a Negro man admitted … and it didn’t work out … he got tuberculosis.” The rejection sent her into depression and despair, according to Lawrence-Lightfoot, who wrote that her mother’s “pain cut right to her soul.” Unwilling to give up, Dr. Lawrence was later accepted to Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons under the condition that white patients in Presbyterian Hospital (now NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving Medical Center) could refuse to be seen by her.

At the College of Physicians and Surgeons (now Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons), Dr. Lawrence was again the only Black student in her class and one of 10 women, all of whom went on to distinguished careers, with several remaining friends, notes Lawrence-Lightfoot in her mother’s biography. She had “never worked so hard at, nor been so rewarded by, her schooling as she was at Columbia,” her daughter wrote. Dr. Lawrence described the work as challenging and productive. She was mentored by Dr. Charles Drew, the only African American on the faculty, and the founder of the modern-day blood bank.

Dr. Margaret Morgan Lawrence in 1983

Courtesy: Sara Lawrence-Lightfoot

Her heart set on becoming a pediatrician, Dr. Lawrence applied for an internship at Babies Hospital (now NewYork-Presbyterian Morgan Stanley Children’s Hospital). Another door was closed when it denied her application, not for lack of qualifications, but because the doctors’ residence was for men only and the nurses’ residence would not take a Black woman.

Instead, Dr. Lawrence pursued her career at Harlem Hospital, a strong training ground more accepting of diversity at the time, returning her to the community where she spent her teen years. “In Harlem, her eyes opened to the connections between physical illness and community health,” wrote her daughter of her mother’s internship. “She saw the corrosive effects of poverty and racism, and recognized that to be a doctor in Harlem meant fighting against the oppressive conditions of her patients’ lives.”

As the internship came to a close, Dr. Lawrence yearned to understand more the connections among history, culture, and disease, and decided to enroll in the Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health in 1943, where she earned her Master of Science. Here, she participated in seminars led by Dr. Benjamin Spock, who focused on the connection between mental and physical health, as well as between the family, community, and society, and who made a strong impression on Dr. Lawrence. Later in her career, she would recall what she learned from Dr. Spock as she was drawn more and more to child psychiatry, according to Balm in Gilead.

A Brilliant Career

As she completed this degree, Dr. Lawrence, almost 30 years old, learned that she and her husband, Charles, a sociologist, were expecting their first child. Though they expected to remain in New York, they were discouraged by their job prospects and traveled to Nashville, Tennessee, where Charles was recruited for a teaching job. Dr. Lawrence also found work teaching preventive medicine and pediatrics at Meharry Medical College, the first medical school in the South for African Americans. She was the only woman on the medical faculty.

A few years later, Dr. Lawrence decided to move back to New York with her family (she and her husband now had three children) to pursue further training in psychiatry. In 1947, she applied for a residency, and in 1948, was the first African American admitted to the New York Psychiatric Institute (then called Columbia’s Psychiatric Institute and located on Columbia’s campus in Washington Heights). She also pursued a fellowship in pediatrics at Babies Hospital — the place that had once rejected her “now welcomed her with open arms,” according to her daughter. She also enrolled at Columbia University’s Psychoanalytic Clinic for Training and Research as its first Black trainee, where she obtained her certification in psychoanalysis.

In 1953, Dr. Lawrence moved to Rockland County, New York, where she became the first practicing child psychiatrist in the county. Dedicated to the underserved and to children’s mental health, her therapy focused on play and artwork. In the opening of Balm in Gilead, Dr. Lawrence recounts working with a 4-year-old who had witnessed his mother being assaulted. Using therapeutic play, she had the child replay the events using dolls and a dollhouse, showing him the powerful role he played in helping his mother, and alleviating the crying and nightmares the child was experiencing. Dr. Lawrence saw helping others as “a privilege,” and sought to help others achieve victory over trauma.

In 1963, Dr. Lawrence returned to Harlem Hospital to head the Developmental Psychiatry Service, where she served for more than 20 years. Until 1984, she was an associate clinical professor of psychiatry in the College of Physicians and Surgeons. She also served on the New York State Planning Council for Mental Health throughout the 1970s and ’80s, and authored two widely used textbooks on treating children with mental impairments. In 1992, Cornell University awarded Dr. Lawrence its Black Alumni Award. She continued to see patients until she was 90 years old.

Lawrence passed away on December 4, 2019 at the age of 105. In reviewing Balm in Gilead, The New York Times hailed Lawrence as a “pioneer therapist of young urban families in Harlem, survivor of seven decades of struggle, change, and achievement.”