Finding Comfort in the Darkness

On Holocaust Remembrance Day, a NewYork-Presbyterian chaplain shares how her mother’s experience as a Holocaust survivor inspired her to serve patients in need of strength and solace.

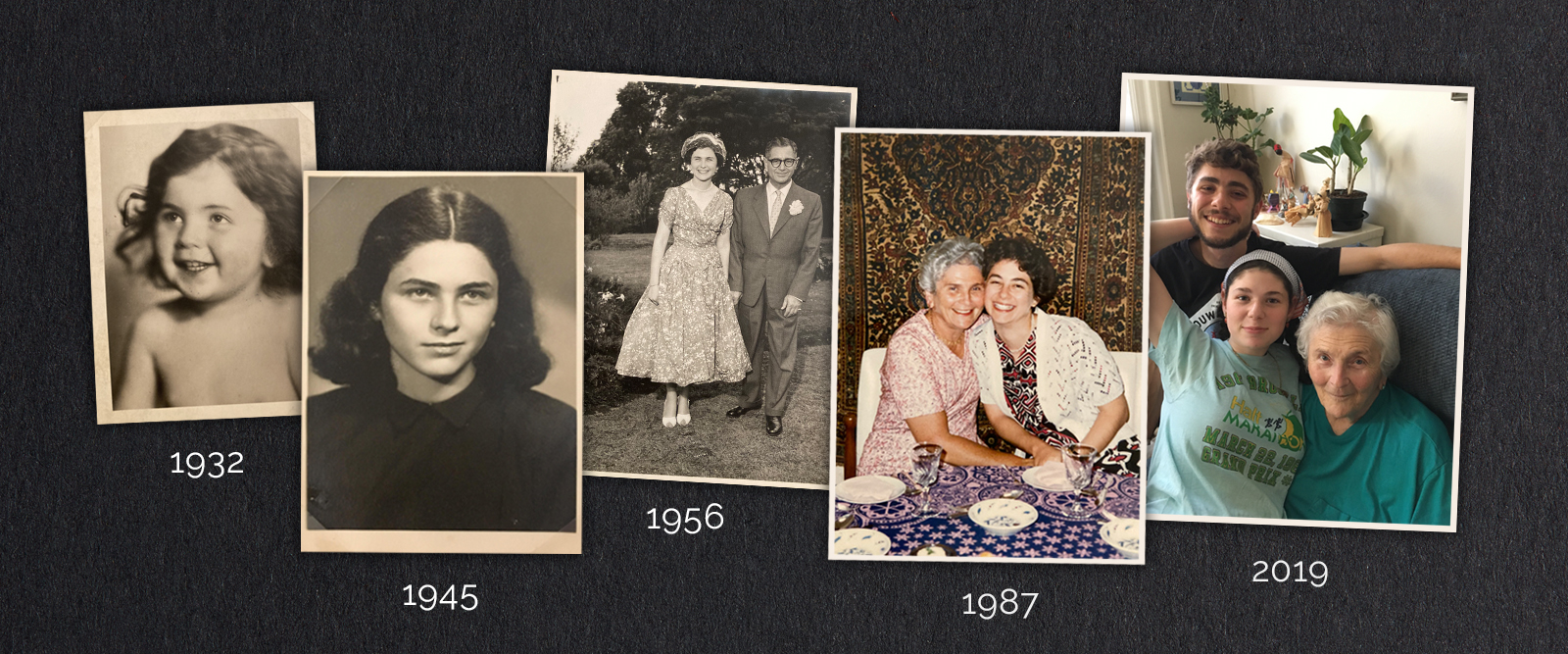

The shelves of Sarah Diamant’s Washington Heights apartment are filled with picture albums. The photographs inside, some more tattered than others, carry cherished family memories, but also serve as a reminder of one of history’s darkest chapters.

Sarah’s mother, Judith Diamant, was only 12 years old when the Nazis rounded her up and deported her from her home in Moravia (what is today the Czech Republic) to Terezin, a way station for European Jews on their way to Auschwitz and other extermination camps. Terrified, Judith was left starving and alone in the lice-infested camp 40 miles north of Prague, eventually leaving two months later.

“After the war, she moved to England to live with an uncle and then she went to Kenya to be an au pair, and there she met my father,” says Sarah. “We lived in South Africa for many years. And after my sister and I came to America to study, my mother came here to New York in 1998.”

Judith Diamant feeds her daughter, Sarah, in May 1959 at their home in Nairobi, Kenya.

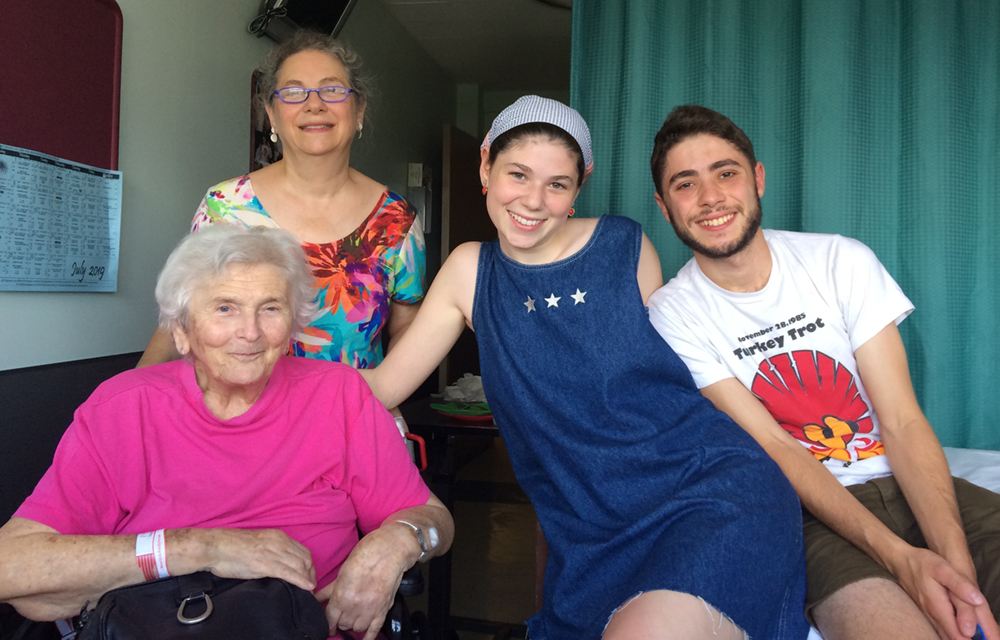

Judith lived near Sarah and her family in New York City, enjoying life as a grandmother to Sarah’s children, Rachel and Samuel, and fully participating in Jewish holidays and other celebrations. In April 2020, Judith contracted COVID-19 and sadly passed away at the age of 87.

Sarah, who had worked for 30 years at the Jewish Theological Seminary, transitioned to residency training and a career as a hospital chaplain at NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center following Judith’s death. In her current role, her mother’s memory serves as a guiding light as she helps patients and families seeking strength during difficult times. “There’s a sense of tremendous comfort and purpose I derive from going into work and being with patients,” says Sarah. “For me, healing comes from doing, from being with others who are in need.”

A Purpose Informed by the Past

One night in March 1945, Judith arrived in Terezin by rail car after being separated from her stepfather. Wearing a yellow star marking her as Jewish, she was marched by the Gestapo into a dilapidated youth barracks with more than 30 other children. Not long afterward, sick with pneumonia and rheumatic fever, she was set to be deported to Auschwitz. As fate would have it, a family friend, who was also at the camp, hid her in the women’s quarters while she recovered, sacrificing her own food rations to save Judith from certain death.

Sarah still finds herself at a loss for words in trying to grasp the horrors of the Nazi genocide, which claimed the lives of six million European Jews and nearly five million others. “How can one communicate individual trauma, or in this case group trauma, on such an enormous scale?” she says. But she also honors Judith’s resilience, as well as the memory of other family members who died at Auschwitz, when working with patients facing uncertainty.

“My mother lived by two pillars — never forget and be open to understanding others’ trauma,” says Sarah. “So I’ve always asked myself, ‘How can I be of service to other people? How can I embrace people amid their deepest suffering?’”

Honoring Her Mother

In the shadow of the Holocaust, Sarah admits that she often struggled to reconcile how her mother always saw the best in people. That changed when Sarah witnessed firsthand the humanity that surrounded Judith and their family when Judith was battling COVID-19.

At the height of the first wave of the pandemic, Judith was rushed to NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving Medical Center. Despite her inability to be by her mother’s side due to restrictions to prevent the spread of the virus, Sarah says the care Judith received from emergency department and other hospital staff, including nurses and chaplains, brought her and her family immense peace.

(From left to right: Judith, Sarah, Rachel, and Samuel.) Judith loved spending time with her grandchildren, who lived nearby in upper Manhattan.

“For one elderly woman to receive so much consideration and so much care, this made me understand what my mother meant by, ‘Always think the best of people,’” Sarah says. “How in her last hours she was able to have this moment of grace, of being received so fully with kindness by hospital staff.”

It’s the same kindness that Sarah strives to show every day to her patients as a chaplain at NewYork-Presbyterian.

“I feel that I really honor my mother very much in the work that I do every day,” says Sarah. “This is a source of remarkable consolation for me. I find comfort in every patient interaction. It’s a comfort that I am always carrying my mother’s memory with me.”