Crohn’s and Colitis: What to Know

Gastroenterologist Dr. Dana Lukin breaks down the symptoms, triggers, and treatments for Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis.

An estimated 1.6 to 3.1 million Americans suffer from inflammatory bowel disease, or IBD, according to the Chron’s & Colitis Foundation, with about 70,000 new cases diagnosed annually.

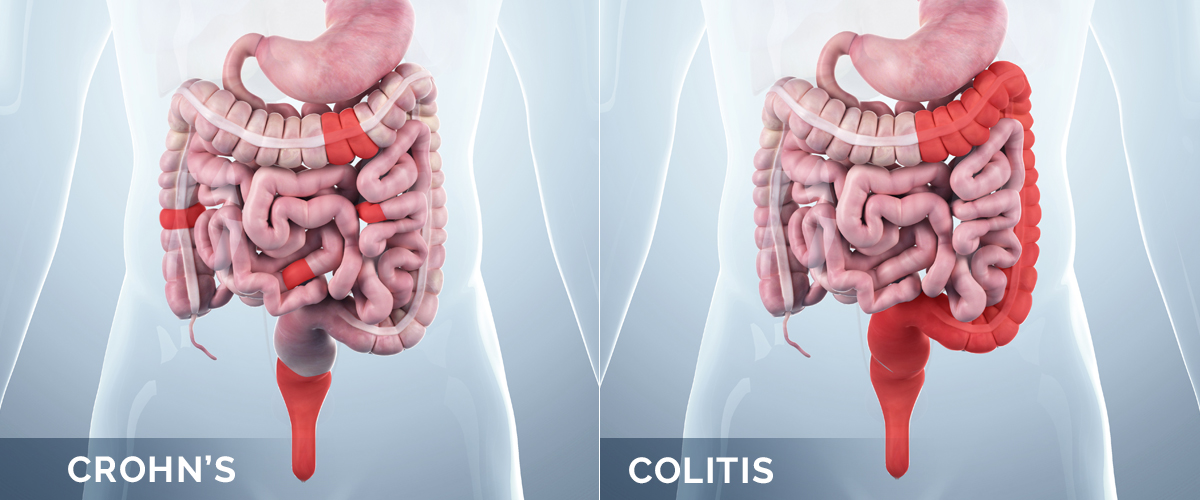

Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis are the most common types of IBD. Both conditions cause chronic inflammation that affects the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, where digestion takes place, but what sets them apart?

Health Matters turned to Dr. Dana J. Lukin, gastroenterologist and immunologist at NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center and assistant professor of clinical medicine at Weill Cornell Medicine, to explain how to recognize the signs, understand the causes, and determine the best treatments for Crohn’s versus ulcerative colitis.

What is the difference between Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis?

The major difference is the area where the inflammation takes place within a person’s digestive system, as well as the degree to which the deeper layers of the gut are involved in the inflammatory process.

What areas of the digestive system do they affect?

Ulcerative colitis affects the large intestine, or colon. The inflammation involves the lining of the colon, leading to diarrhea, blood in the stool, abdominal pain, urgency, and weight loss, among other symptoms.

Crohn’s disease can affect all areas of the digestive tract, from the mouth to the anus, and may penetrate through the intestinal wall to involve the connective tissue surrounding the gut. This may lead to some of the complications related to Crohn’s disease, such as narrowing of the intestine (known as stricture), abscess formation, or the formation of abnormal connections from the bowel to other structures (known as fistula).

In Crohn’s, you can have healthy parts of the intestine mixed in with inflamed areas, whereas with ulcerative colitis, you have continuous inflammation of the colon.

What causes someone to have an inflammatory bowel disease like Crohn’s or ulcerative colitis? Is it genetic, or can it occur without any family history?

The cause of IBD is unknown and the genetic features are complex. Whereas family history is the most significant risk factor, inheritance is not straightforward. Changes in the intestinal microbiome, which is the collective microorganisms and their metabolic products within the intestine, are a hallmark of IBD. These changes have the potential to activate abnormal immune pathways in patients with a genetic predisposition.

Other potential triggers may include cigarette smoking, use of antibiotics and other medications, dietary additives, gastrointestinal infection, and others. Once the immune system is activated, the body cannot turn off this pro-inflammatory circuit. Therefore, the immune system can no longer perform its protective function and the dysregulated immune activation leads to ongoing inflammation.

IBD may appear at any age, from infancy until your 80s and 90s. It is most common in the teens and 20s, but unlike many diseases with a genetic predisposition, it may emerge many decades after birth. There is an increasing incidence among adults over 50 years of age.

Dr. Dana Lukin

What symptoms might someone experience with Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis?

Crohn’s disease symptoms vary, but the most common are abdominal pain, diarrhea, and weight loss. Other frequent symptoms include abdominal bloating, constipation, blood in the stool, fevers, or perianal irritation from fistula formation, which occurs when an abnormal connection forms between part of the GI tract and the skin or another organ. Children may fail to meet growth expectations if Crohn’s disease is diagnosed during childhood or adolescence. In severe Crohn’s disease, fatigue and nutritional deficiencies may be seen.

Ulcerative colitis tends to present with diarrhea, with or without bleeding. Other common symptoms are abdominal pain, weight loss, fatigue, mucus in the stool, and urgency for bowel movements. Often, patients will experience tenesmus, the sensation of needing to have a bowel movement without the ability to do so due to rectal inflammation.

Symptoms occurring outside of the intestines with both Crohn’s and ulcerative colitis include joint pain in the spine, lower back, and peripheral joints; inflammation in the eyes with blurry vision, redness, and/or eye pain; cold sores in the mouth (aphthous ulcers); skin rash or ulcer; kidney stones; and blood clots.

How can you test for Crohn’s or ulcerative colitis?

When IBD is suspected, routine laboratory tests, imaging studies, and endoscopic evaluation can be helpful in establishing a diagnosis. Complete blood counts may assess for anemia. Certain blood tests can measure the degree of inflammation present in the body, while a stool analysis can distinguish inflammatory causes of diarrhea from functional causes, such as irritable bowel syndrome (IBS).

If there is significant abdominal pain, weight loss, or fevers, cross-sectional imaging with a CT scan or MRI enterography are useful in detecting inflammatory changes in the small and/or large intestine. Ileocolonoscopy with biopsy is the gold standard for assessing for IBD. This can detect visible inflammation and also allows for tissue biopsies to look for the presence, type, and severity of inflammation while excluding other sources of inflammation.

While there are several commercially available blood tests aimed at helping diagnose IBD, they are not reliable or well-validated to establish a definitive diagnosis.

Are Crohn’s and ulcerative colitis life-threatening?

The vast majority of IBD cases are not life-threatening. Fortunately, medical and surgical therapies have advanced in recent years, making complications less common. A proactive approach to disease management is important to understand one’s risk for complications and to tailor an approach to therapy aimed at minimizing progression.

What should people keep in mind if they are diagnosed with IBD?

The first thing I recommend is to ask a lot of questions. I spend the first visit after diagnosis understanding each patient’s journey to their diagnosis, as it is unique for each patient, and learning the impact of disease on daily life. It is important that patients feel comfortable asking questions and understand the diagnosis and potential impact of disease over time. An informed patient is an empowered patient.

Most patients with IBD can live a normal life. Effective therapy for Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis can help improve a person’s quality of life, allow them to engage in all activities, and have complete family lives.

For example, if a patient is considering pregnancy while living with IBD, the most important factor is to involve the gastroenterology team and OB-GYN in planning for pregnancy, with a goal of achieving objective remission before attempting conception, as disease in remission is associated with the most favorable pregnancy outcomes. Discuss your medication plan (most medications are safe for pregnancy and breastfeeding) and do not make any changes without consulting with your IBD team.

What are the treatment options for Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis?

While Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis are chronic diseases with no known cures, there are several effective treatment options. Initial treatment should follow a complete laboratory, imaging, and endoscopic evaluation to determine whether a patient is experiencing mild-to-moderate versus moderate-to-severe disease.

Once the severity is assessed, there are five basic categories of medications that may be used to help induce remission, prevent flare-ups, and ultimately improve one’s quality of life. Those include aminosalicylates (a class of drugs used to reduce inflammation in the lining of the intestine), corticosteroids (often known as steroids), immune modulators (a class of drugs that helps activate normal immune function), biologic therapies, and small molecule therapies.

Ultimately, the goal is to avoid long-term steroid use and to maintain remission with effective anti-inflammatory therapies. Our guidelines also highlight the importance of achieving healing of all endoscopically visible inflammation, which has been associated with the best longterm clinical outcomes.

With each advancement in IBD research and treatment options, we are moving closer to finding a cure.

Dr. Dana Lukin

Are there recommended diets to follow for those who suffer from IBD?

At this time, there is no universally accepted diet used in IBD. Most patients do experience food-related symptoms and there has been much speculation about the use of specialized diets to help manage symptoms of IBD. Unfortunately, there are limited data from well-designed clinical trials to inform the routine use of any particular diet.

In general, a balanced whole-foods Mediterranean diet is advised for most patients. In Crohn’s disease with obstruction or stricture, a low-residue diet (avoiding tough meats, raw vegetables, roughage, or nuts) may limit pain or obstructive episodes, but these foods may be consumed if blended or used in modified forms, such as nut-butters rather than whole nuts. For active ulcerative colitis, roughage and high-fiber diets may irritate the colonic wall, leading to diarrhea, urgency, and other symptoms, so a diet lower in fiber may be used during flare-ups. Limiting dairy, higher FODMAP foods (which may cause bloating and/or diarrhea), alcohol, and greasy foods may help minimize symptoms. However, the least restrictive diet on which a patient has few-to-no symptoms is recommended. Additionally, while dietary modification may reduce symptoms from IBD, we do not have substantial evidence that diet can effectively reduce inflammation when used in place of medical therapy in most patients.

If you suspect you might have an IBD, when should you see a doctor?

If you have frequent or severe abdominal pain, diarrhea, or weight loss, it’s a good idea to have a medical evaluation. Other warning signs include bloody diarrhea, fevers, or inability to have a bowel movement. New swelling of an arm or leg, skin ulceration, or worsening of any of the above-mentioned symptoms should prompt an evaluation.

Any promising research in the treatment of IBD?

There are many exciting developments in the treatment of IBD. These include novel surgical treatments aimed at sparing the removal of bowel during surgery, new stem-cell therapies for perianal fistula, and numerous pharmaceutical clinical trials aimed at the development of treatments for both Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. Medical therapy is focused on developing safer medications, oral medications, and those that can deliver medication in a targeted manner.

In the next few years, several new therapies are expected to come to market. Additionally, therapies that impact the composition of the microbiome have been investigated. These therapies are aimed at correcting the underlying abnormalities in bacterial composition (dysbiosis) associated with IBD or the eradication of specific bacteria thought to impact disease activity.

Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis are complex chronic conditions but there have been many advances that have helped us understand the diseases and the development of highly effective therapies. Ensuring that a patient with IBD has a multidisciplinary care team has been associated with higher treatment success rates and an improved quality of life. With each advancement in IBD research and treatment options, we are moving closer to finding a cure.

Learn more about IBD treatment and services at NewYork-Presbyterian.

Dana Lukin, M.D. , Ph.D., is a gastroenterologist and immunologist at NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center and is the clinical director of Translational Research for the Jill Roberts Center for Inflammatory Bowel Disease at Weill Cornell Medicine. Dr. Lukin specializes in the care of patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), including Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. He is actively involved in collaborative research projects with the New York Crohn’s and Colitis Organization, IBD ReMEdY, and the Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation Clinical Research Alliance.