After Nearly Losing Her Eye in a Bungee Cord Accident, a Nurse’s Colleagues Saved Her Sight

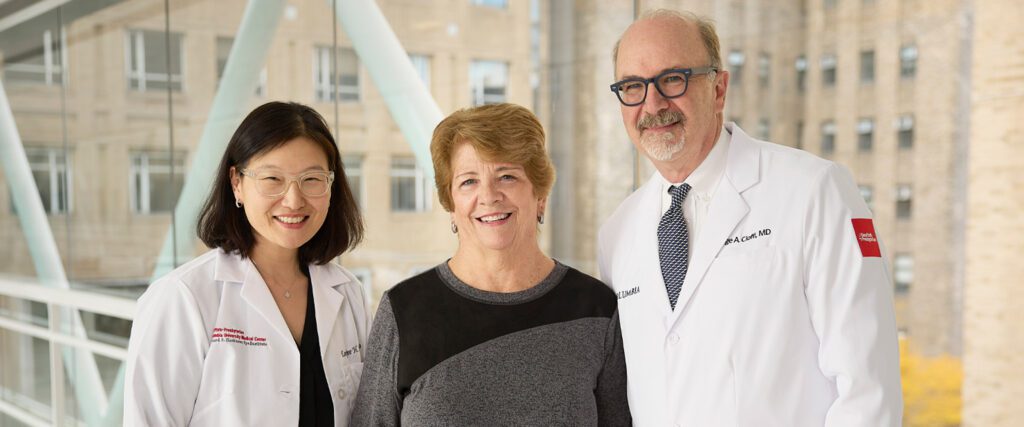

When a bungee cord snapped and struck her eye, nurse Irene Fico turned to the ophthalmology team at NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving Medical Center, hoping they could preserve her sight. After a series of surgeries, they gave her close to perfect vision and helped her maintain it over a decade of care.

Thirteen years ago, Irene Fico and her husband, Tom, were heading up to the Adirondacks for a camping trip and stopped by a neighbor’s house to borrow a canoe for the weekend.

“We loaded the canoe on the roof of the car, and we had to use bungee cords to secure it,” Irene recalls. “I was sitting in the back seat, reaching up to latch one end of the bungee cord to the roof. When I let go, the bungee cord snapped right back and hit me in the eye.”

Irene, a nurse at NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving Medical Center for more than 40 years, knew immediately she needed to get to a hospital. She went to a local emergency department, where she learned her left eyeball was ruptured, and she would need expert care to repair it. “There was no question where I was going to go,” she said.

Later that night, Dr. George (Jack) Cioffi, the chief of ophthalmology at NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving Medical Center, remembers receiving a call at midnight about a nurse being transported to the emergency department with a bungee cord injury.

“It was my first week on call as the chief, and she was one of our own,” says Dr. Cioffi. “I like to think that Irene and I were both at the right place at the right time.”

A Delicate Repair

The impact of the bungee cord on Irene’s eye was severe: A deep cut stretched across her eyeball, from the cornea (the front of the eye) to the sclera (the white part of the eye).

After an initial evaluation, Dr. Cioffi decided to schedule surgery for Irene early in the morning; the first priority was to save her eye. When it was time for the operation, Irene remembers she recognized the anesthesiologist as one of the doctors she worked with every day. “I just started crying,” she says. “But I knew I was in great hands, and he reassured me everything was going to be OK.”

For the surgery, Dr. Cioffi worked under a microscope, examining the wound to see how far the trauma extended. He then sewed the surface of her eye back together using microneedles and about a dozen sutures smaller than a human hair. “We had to close the eye back up so it could reform,” says Dr. Cioffi. “It had shrunken to more like a raisin than a grape. We had to make it back into a grape.”

After Dr. Cioffi finished the repair, Irene was able to go home the same day to start healing. A month later, she went back to work in the endoscopy unit at NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia.

“Repairing an eye is a team sport — we had everything from the expertise of the nursing staff to an anesthesiologist who knew how to deal with a traumatized eye,” says Dr. Cioffi. “It was a pretty bad injury, but we took it one step at a time and made a plan to restore her sight.”

From Trauma to Perfect Vision

While Irene’s eye was successfully saved, she still needed ongoing care, including a series of surgeries to fully regain her vision and maintain it.

The bungee cord injury caused an immediate traumatic cataract, which is a clouding of the lens. Her iris (the colored part of the eye) was damaged. And the laceration of the cornea was so severe that she needed a cornea transplant.

Six months after the initial repair, Dr. Leejee Suh, an ophthalmologist and cornea specialist at NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia, led the surgery to rehabilitate Irene’s eye: She removed the damaged cornea and transplanted a donor cornea; pieced together the iris to restore Irene’s natural, light blue eyes; and replaced the lens with an artificial one to treat the cataract — a challenge because both the lens, and the network of fibers that hold the lens in place (called zonules), were damaged.

“Irene went from close to no vision to 20/25 afterwards,” says Dr. Suh. “It’s extremely rare to give a patient almost perfect vision after so much trauma to the eye.”

Over the years, Irene has continued to see Dr. Suh and Dr. Cioffi for follow-up care.

In 2019, and again in 2024, her cornea transplant deteriorated, due to an infection. Dr. Suh treated it with an innovative, minimally-invasive technique — instead of replacing the entire cornea, she did a partial cornea transplant, called Descemet’s Stripping Automated Endothelial Keratoplasty (DSAEK), in which only the inner layer of the cornea is replaced to restore the health of the original transplant.

In 2019, she also developed glaucoma, a common eye disorder that affects the optic nerve. Because of the severe eye trauma, the fluid in the front of her eye was not draining properly, which raised the pressure on the eye and stress on the optic nerve. To relieve the pressure, Dr. Cioffi, a glaucoma specialist, implanted a tiny tube (called a micro-shunt) that created a new drainage pathway for fluid.

“When new issues arise with Irene’s eye, we help address them, and she’s just sailed through, and part of it is her positive attitude,” says Dr. Cioffi. “She’s loved by all of her colleagues. She’s an excellent nurse and she takes pride in her work.”

Looking Ahead

Irene still works at the endoscopy unit, though now she’s retired and working per diem in admissions instead of assisting with procedures. “I love talking to patients and listening to their stories,” she says. “It helps alleviate their fears and stress before their procedure.”

Outside of work, Irene and her husband travel and still go camping in the Adirondacks with their two dogs, Abby and Kandy. Last year, she also became a grandmother, so she regularly visits her daughter to take care of her granddaughter.

When she has checkups with Dr. Suh, they share stories about their families. “I can’t believe it’s been all this time,” says Irene. “I’m very grateful to Dr. Suh and Dr. Cioffi, they are both very special to me. They literally saved my eye and gave me back my sight.”