A Paramedic Reflects on the Days After 9/11

NewYork-Presbyterian paramedic Steven Friend recalls his experience performing triage, and remembers the colleagues he lost.

Like most New Yorkers who experienced the tragic days and nights post-September 11, 2001, Steven Friend remembers the sights, sounds, and sensations as if they happened yesterday. The fires burning underground for days on end, the noxious smell, and the dust and ash coating the city are fresh in his mind.

“One of the ways you could tell someone had been down there was by looking at their shoes, which would have been covered in the dust that was everywhere,” says Friend, who has been a paramedic at NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center for 30 years.

He remembers exactly where he was the morning the planes hit.

“We were on the North Shore of Lake Superior, in a beautiful B&B, when we got the news,” says Friend, now 61, who was vacationing with his wife, Abby, a former flight nurse and a NewYork-Presbyterian employee for 31 years. Their relaxation ended at checkout, when the woman behind the desk asked, “You guys are from New York, right? We heard something about a plane hitting the Twin Towers.”

Like many people, Friend initially assumed a small aircraft had accidentally veered into one of the buildings. But when the couple turned on their car radio and learned there had been a terrorist attack on the World Trade Center, they were stunned. They quickly made the decision to return home to New York City.

“If you’re in the profession I am, and you know your co-workers might be in danger, your impulse is to go to where you are needed the most,” says Friend.

Steven and Abby Friend

Going anywhere was a challenge, since there were no flights to New York City — or anywhere else in the country.

“We called our rental car company and said, ‘We’re both medical personnel from New York City and we need to get back,’” he recalls. “They said, ‘No problem. Take the car and return it whenever you can.’”

The couple then drove the 1,394 miles back to the city over the next two days. They arrived in New York on September 13.

“We needed both our driver’s licenses and hospital IDs in order to be allowed to cross the George Washington Bridge and enter Manhattan,” says Friend. “Looking down the Hudson and seeing plumes of smoke where the towers were felt surreal — apocalyptic almost — like something you would see in a movie.”

A New Reality

Friend didn’t have much time to adjust. After quickly changing into his uniform, he immediately went to work, offering to help in any way he could. He was assigned to the ambulance he would normally be on, patrolling Midtown for an eight-hour shift.

By then, he knew that several of his colleagues had been down by the World Trade Center at the time of the attack and that attempts to reach them had been unsuccessful.

For me, knowing they were still unaccounted for was the hardest part. It was always on my mind.

Steven Friend

“There were still emergencies going on in the rest of the city,” Friend says. “I had to do my job, but it was tough to stay focused. We wanted to help our co-workers who were down there. We didn’t know if they were alive and were waiting to be rescued or had passed away.”

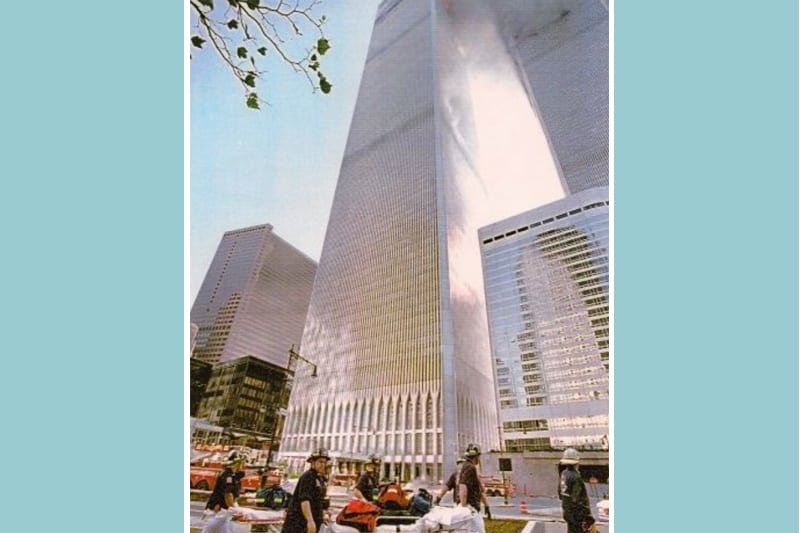

It wasn’t until his shift ended that Friend was redeployed downtown, first to a staging area by a pier near Ground Zero, then to what was known as a forward triage station at West and Vesey streets, directly across from the remains of the World Trade Center.

He spent the better part of the next three days at the triage station. “When the sun came up, you’d see the rays shining through the shards of the buildings that were still standing.”

By then, there were no more lives to be saved. Now it was time to help the rescuers who were digging and searching for those lost when the towers came down.

Friend and his fellow paramedics began helping first responders who were working on the “pile,” the name given to the mass of debris. Many had eye injuries or had injured themselves in other ways looking for survivors.

“There were dozens and dozens of people frantically digging, people who wouldn’t even come down when they were hurt or exhausted,” Friend says, “because at the time, we still didn’t know if there were survivors under there.”

The missing included Keith Fairben and Mario Santoro, two full-time NewYork-Presbyterian EMTs.

“They were among the first who made it down there after the planes hit,” says Friend.

Also missing were two paramedics who worked with both NewYork-Presbyterian and full time with the New York City Fire Department — Lt. Kevin Pfeifer and James Pappageorge.

“For me, knowing they were still unaccounted for was the hardest part,” says Friend. “It was always on my mind.”

Those four colleagues, Keith and Mario, Kevin and James, died on 9/11. Every year, their colleagues gather at the Memorial constructed in their honor at NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center.

This year is no different.

“It’s always a hard day,” says Friend. “We observe a moment of silence at the Memorial, then the hospital holds a service in the chapel. People we haven’t seen in a while who worked for NYP at the time, along with many other hospital employees, join together.

“The EMS Memorial is a place to remember the co-workers we lost and the sacrifice they made to help their fellow man.

“The hospital has supported us in many ways, including the construction of this Memorial. NewYork-Presbyterian has always done its best to step up in times of crisis.”

Yet the wounds of 9/11 remain. Seventeen years later, Friend has never been back to Ground Zero.

“People have different ways of handling things,” he says. To this day, he doesn’t go anywhere without his passport and hospital ID. “You just never know when something will happen and you’ll need them to get back into New York.”

Like always, Friend is determined to be prepared, to go wherever he is needed.

“If you’re in this profession,” he says, “the natural thing is to want to help others.”