What to Know About Epilepsy

NewYork-Presbyterian experts explain this common condition and how it’s diagnosed and treated in children and adults.

Epilepsy is a neurological condition that causes a disruption in the electrical network of a person’s brain. These disruptions send irregular signals to the rest of the body, and the result is what we know as a seizure. Approximately 3.4 million people in the United States live with this condition, which means there are more people living with epilepsy than with autism spectrum disorders, Parkinson’s disease, multiple sclerosis, and cerebral palsy combined, according to the Epilepsy Foundation.

Despite the common diagnosis, misconceptions about epilepsy abound. For example, seizures do not always involve violent convulsions. Many epileptic seizures are subtle and last only a few seconds. With medication or surgery, the condition can usually be treated successfully.

“It’s important for people to know that there are many types of epilepsy, especially in children,” says Dr. Alison May, a pediatric neurologist with the Epilepsy Monitoring Program at NewYork-Presbyterian Lawrence Hospital. “Many people think of epilepsy as being only one specific type, where children have convulsions and significant cognitive impairment. But it can look very different, and families should know that epilepsy does not mean a lifetime of seizures with learning disabilities.”

“There shouldn’t be a stigma attached to epilepsy,” adds Dr. David Chuang, an assistant attending neurologist with NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center. “Most people control their epilepsy with anti-seizure medications and are able to lead a perfectly normal life.”

For Epilepsy Awareness Month in November, Health Matters spoke with Dr. Chuang, who is also an assistant professor of clinical neurology at Weill Cornell Medicine, and Dr. May, who is an assistant professor of neurology at Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons, to learn more about living with epilepsy and how it affects adults and children.

Dr. David Chuang

What is an epileptic seizure?

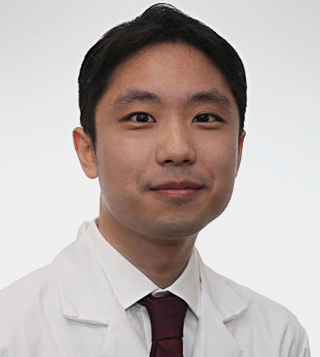

An epileptic seizure involves abnormal electrical activity of the neurons in your brain, says Dr. Chuang. A person will get different seizure symptoms depending on where this abnormal electrical activity started in the brain, and if it spreads to other parts of the brain.

The seizure can just stay in one part of the brain, or it can spread, adds Dr. May. A seizure is considered to be a generalized seizure if the whole brain is implicated, or it can be a focal seizure, where just one part of the brain seems to be activated.

If you have a seizure, does that mean you have epilepsy?

No. Epilepsy means you have an unprovoked seizure, with a high risk of having more unprovoked seizures, says Dr. Chuang. There are other conditions that can cause seizures, such as hypoglycemia (low blood sugar) or alcohol withdrawal. If these are the causes of a seizure, that person wouldn’t be classified as having epilepsy, because in those cases, those are provoked seizures and you just have to address the underlying condition.

What does a seizure look like?

There isn’t one type of seizure, explains Dr. Chuang. They can range from an odd sensation, such as experiencing a weird taste, a feeling of déjà vu, or staring blankly, all the way to the big convulsions that you might see in movies or TV shows. They can last anywhere from several seconds to several minutes. Some people who have epilepsy might have a seizure once a year, but some people might have several seizures a day.

If the symptoms can be subtle, how can you tell if you’ve had a seizure?

With epilepsy, the seizures in a person are recurrent, and they tend to look the same, says Dr. Chuang. For instance, if a person consistently experiences the same odd smell or the same kind of twitching, then that puts it on the radar as a possibility of epilepsy that should be checked out by a doctor.

Signs and Symptoms of a Seizure

A person will experience different symptoms depending on where a seizure starts in their brain.

How is epilepsy diagnosed?

The gold standard for making the diagnosis of epilepsy is to capture the actual seizure on video electroencephalogram (EEG). This is a procedure where doctors video a patient while monitoring the electrical activity in the brain so they can try to capture a seizure on video and correlate that to the patient’s brain activity. However, it can be hard to capture seizures on an EEG, says Dr. Chuang. Other supporting tests that can help make the diagnosis are taking a careful history of the patient to see if what they experience is consistent with seizures, or using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to see if there are abnormalities in the brain that can cause seizures.

Once epilepsy is diagnosed and the doctor knows if it’s a focal or generalized seizure, then they can decide which medicine would be the best choice.

Dr. Alison May

Are the symptoms and diagnoses the same in adults and children?

The symptoms and how epilepsy is diagnosed are generally the same in adults and children, but with a few key differences, says Dr. May. Some children might be too young to explain what’s going on, where they feel something — they don’t have the words to express it. In that case, a provider will ask parents a lot of questions, because a diagnosis will depend in part on caregiver reports and what they observe. Caregivers may be asked to send videos so their doctor can see what’s happening.

If a child seems to space out and they don’t respond to having their name called or being touched, or if there is a pause or regression in a child’s development, or a sudden challenge academically that wasn’t there before, those can also be markers that something’s going on in the brain. If there are concerns, parents should speak to their pediatrician and get a referral to a neurologist. Getting a referral is easy, and there is no risk from getting an EEG to see if your child is struggling with seizures.

What causes epilepsy?

There are a number of causes. For adults, says Dr. Chuang, epilepsy is caused by an injury to the brain — whether it’s from a stroke, a brain tumor, head trauma, a brain infection, or a bleed in the brain such as a ruptured aneurysm or subarachnoid hemorrhage. Many adults also have epilepsy due to a small, abnormal brain development that may not lead to symptoms for most of their lives but will cause them to have epilepsy in adulthood. It is also not uncommon for a cause of epilepsy to not be identified.

In children, adds Dr. May, there are some age-related conditions that are more likely to cause epilepsy, such as genetic changes or a hypoxic ischemic injury to the brain. A hypoxic ischemic injury is like a stroke but it occurs during delivery, where the baby has lost oxygen to their brain. Seizures caused by cortical dysplasia, which is a developmental anomaly where part of the brain does not form properly, is more common in children than adults.

How is epilepsy treated?

Virtually everybody, children and adults, diagnosed with epilepsy would be started on an anti-seizure medication. If the first medication doesn’t work, your doctor might add a second or a third medication, but if those don’t work then epilepsy surgery could be considered, if the patient qualifies for it. With epilepsy surgery, doctors first locate where in the brain the seizures are coming from, and, if they can do so without causing any significant negative side effects, they will remove that area of the brain, explains Dr. Chuang.

If medications don’t work and a patient isn’t a candidate for surgery, another option would be neurostimulation. This involves surgically placing a device either under the skin on a person’s chest to stimulate the vagus nerve (a nerve that runs from the brain through the chest), or directly on the brain, to send electric signals that help manage seizures.

Can epilepsy be cured?

Typically, people with epilepsy end up taking their medication for the rest of their lives, says Dr. Chuang. Some people will stop having seizures when they are taken off medication after epilepsy surgery, and there are some people who stop taking their medication because they’ve been seizure-free for a very long time, and after they stop the medication they actually stay seizure-free.

Can children grow out of epilepsy?

Yes. Some childhood epilepsy syndromes can be outgrown, explains Dr. May. This is different from what exists in adults. Some children can present with seizures at an early age and they may outgrow them when they get older, typically around teenage years. The goal is always to achieve what Dr. May calls “seizure freedom,” meaning no seizures, and then, based on a thorough evaluation, determine if the child is able to come off their medications. If a child has a normal EEG, normal MRI and normal development, he or she would be a good candidate to try to wean off medication when they achieve two years of seizure freedom. Doctors don’t really know why children grow out of their epilepsy, but scientists are researching this to learn more.

If you or a loved one is diagnosed with epilepsy, what’s important to keep in mind?

Epilepsy can be a scary diagnosis, says Dr. Chuang. If it’s not controlled, a person can’t do a lot of things by themselves, like swim or drive a car, because they never know when they’ll have a seizure. However, those with well-controlled epilepsy, whether it’s through medication or surgery, are usually able to live a normal life.

Additional Resources

Learn more about the epilepsy services at NewYork-Presbyterian.

For more on the Epilepsy Monitoring Program at NewYork-Presbyterian Lawrence Hospital, click here or call 914-787-5000.

To learn more about The Epilepsy Center at Weill Cornell Medicine and NewYork-Presbyterian, click here or call 212-746-5519

Click here or call 646-426-3876 for more on Columbia University’s Comprehensive Epilepsy Center