Targeting Advanced Prostate Cancer

A new high-tech treatment may change the odds for NewYork-Presbyterian patients battling the disease.

It’s a disease so pervasive that many people don’t realize its severity. But prostate cancer, the third most common type of cancer, killed nearly 27,000 men in 2016, according to the American Cancer Society.

While it’s true that most of those who are diagnosed with prostate cancer do not die of it — 2.9 million who’ve had the disease are alive today — chances of long-term survival plummet if the cancer spreads.

That may be about to change, thanks to a new therapy offered in clinical trials at NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center known as directed radioisotope therapy. Because it precisely targets cancerous prostate tumors without harming other cells, it holds promise for effectively treating men for whom surgery or radiation alone is not necessarily the best option, including men with aggressive tumors.

“We haven’t been curing men with metastatic prostate cancer,” says Dr. Scott Tagawa, an associate attending physician at NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center and an associate professor of clinical medicine and urology and the medical director of the Genitourinary Oncology Research Program at Weill Cornell Medicine. “But with this new treatment, we can potentially help those who couldn’t be cured before.

“There are plenty of high-risk cases where surgery or radiation is not curative,” he explains. “Something that could track down and kill the rogue cells outside of the prostate could increase the cure rate in combination with surgery or prostate radiation. I’m very excited about the future.”

What Makes Prostate Cancer Unique

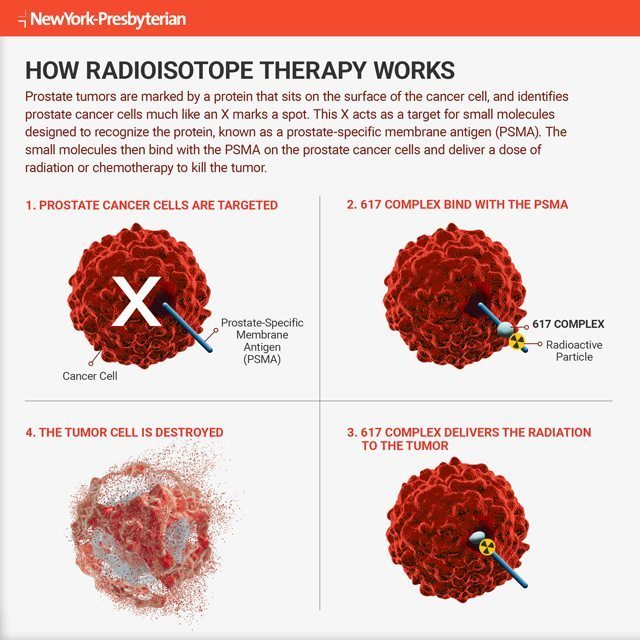

Prostate tumors are marked by something called PSMA, which stands for prostate-specific membrane antigen, a protein that sits on the surface of the cancer cell.

“Prostate cancer is one of the very few cancers in the world that has something located on the cancer cell and basically nowhere else in the body,” says Dr. Tagawa.

That’s important because it means that PSMA can serve as a marker or identifier for prostate cancer cells — a big red X marking the spot, so to speak. These X’s, which basically “hang out over the side of the cell,” as Dr. Tagawa puts it, provide an ideal target for anti-PSMA antibodies, or small molecules that act as “carriers” designed to recognize and bind with PSMA. Essentially, the anti-PSMA antibodies merge with the PSMA on the prostate cancer cells like a lock and key.

“These courier antibodies … can carry whatever we want to put on them, whether a small radioactive particle or a chemotherapy drug,” says Dr. Tagawa. “We inject them into a patient’s bloodstream, and they go straight to the PSMA on the cancer cells, killing the tumors without harming surrounding healthy cells in the prostate or in other areas of the body.”

Seeking Out and Destroying Hidden Tumors

Before treatment, however, comes diagnosis, and this novel therapy is also creating new hope for better, more precise diagnoses.

“What often happens is that a patient’s PSA number goes up, but we can’t see anything on an MRI or PET scan,” says Dr. Tagawa. (PSA is a protein made by the prostate gland; high levels in a blood test may indicate cancer.)

With PSMA imaging, attaching a radiotracer to an anti-PSMA antibody or small molecule allows physicians to “see” the PSMA on the cancer cells in hiding, the ones responsible for the rising PSA numbers, he explains.

“With this new treatment, we can potentially help those who couldn’t be cured before.”— Dr. Scott Tagawa

“Because of PSMA imaging,” says Dr. Tagawa, “we can see what we couldn’t see before.”

This kind of imaging can also pinpoint more aggressive tumors so treatment can be tailored accordingly — thanks again to PSMA.

“PSMA tends to be higher per cell in more aggressive tumors and in those that have spread beyond the prostate,” says Dr. Tagawa. “We take advantage of that by using PSMA imaging to find these ‘hot spots’ in the body.”

The more hot spots that appear on the scan, the more aggressive the cancer is likely to be. That knowledge is especially crucial for patients who may be taking a watch-and-wait approach to their treatment, undergoing periodic monitoring rather than radiation or chemo. Hot spots are like an early-warning system that suggests stronger measures are needed.

Treatment That’s Lethal to Tumors, Not Patients

Stronger measures generally mean a high dose of radiation or chemo. Indeed, a raft of studies at NewYork-Presbyterian and other cancer centers has shown that when it comes to prostate cancer, the higher the dose of radiation, the better the response, and the longer patients survive.

“The prostate is radio-sensitive. Most men who get radiation are cured,” says Dr. Tagawa.

In some men, however, the cancer continues to grow, spreading throughout the prostate and beyond. If higher doses of radiation are necessary, it can damage the rest of the body if not carefully targeted. That led NewYork-Presbyterian and Weill Cornell Medicine physicians to a new strategy: combine a radioisotope with a small molecule that binds to PSMA. This therapy would enable physicians to specifically target the PSMA-expressing cancer and minimize damage to healthy organs and tissue.

In January, Dr. Tagawa and his team began conducting trials in which patients are injected with this highly targeted form of radiation therapy. The radioactive particle known as lutetium-177, or Lu-177, is attached to a small molecule called 617 — the PSMA-seeking missile. The duo is then injected into the bloodstream of men with metastatic prostate cancer. Successive groups of patients will continue to get ever-higher doses for better results.

“We’ll keep going up until we start to see any significant side effects,” says Dr. Tagawa. “In theory, we can even try attaching both radiation and a drug.”

Some refer to this type of high-tech cancer treatment as “personalized medicine.” Dr. Tagawa prefers “precision medicine.”

“In a way, this would be the most tumor-targeted treatment out there — only going to places where PSMA exists,” says Dr. Tagawa. “And the nice thing about prostate cancer is that it’s pretty much the only site in the body with a significant amount of PSMA.”

Better still, Dr. Tagawa says that theoretically, using anti-PSMA carriers and PSMA-sensitive radioisotopes to seek and destroy tumor cells should work for 90 percent of patients.

“As long as we can get a high enough dose of radiation to the tumor, the cell will die and we can avoid the rest of the body,” he explains. “This is going to help a lot of people around the world.”