Obsessive Compulsive Disorder Explained

An anxiety expert discusses the signs, causes, and most effective treatments for OCD.

Many people like things “just so,” or have obsessive thoughts and compulsive behaviors. But for an estimated 2.2 million adults, or 1% of the U.S. population, these thoughts and behaviors can control their lives and interfere with their ability to function.

“A lot of people may have obsessive thoughts and compulsive behaviors that make them feel better, but just because you’re extra clean or organized doesn’t mean you have obsessive compulsive disorder,” says Dr. Avital Falk, program director of the Intensive Treatment Program for OCD and Anxiety in collaboration with the Center for Youth Mental Health at NewYork-Presbyterian and director of the Pediatric OCD, Anxiety, and Tic Disorders Program at Weill Cornell Medicine. “For those truly struggling with obsessive compulsive disorder, it can be quite debilitating.”

How do you know if you or someone you love has obsessive compulsive disorder? And what can you do about it? Health Matters spoke with Dr. Falk about how to recognize the signs of OCD, when to seek help, and how to treat it successfully.

What is obsessive compulsive disorder?

Dr. Falk: Obsessive compulsive disorder is characterized by recurring intrusive thoughts, images, or urges. For each person, these obsessions can look very different — OCD plays on whatever is horrifying for each individual, and the compulsions are the behaviors or rituals that the person performs to quiet the obsessions, calm themselves down, and get some relief.

What are some examples of OCD?

A classic example of OCD is someone whose obsession is about getting sick or being contaminated by germs, or who doesn’t like feeling dirty and worries that they can’t handle the sensation, and engages in the compulsion of washing their hands over and over to bring at least temporary relief from the concern over feeling dirty.

For some, superstition may accompany a compulsion. For example, someone with OCD may feel that they need to do things in threes, otherwise something bad will happen to them or a family member. Or they have to check something, like that the stove is off or a door is locked, a certain number of times. The more that they do the compulsion, the more they think, “I guess that worked!” Even if on some level they know it is not logical, the behavior is reinforced.

Dr. Avital Falk

What is the difference between liking cleanliness and order and having OCD?

OCD takes up a lot of time and interferes with a person’s ability to function. The compulsion controls them and can prevent them going to work, answering emails, and, if they are a child, from going to school.

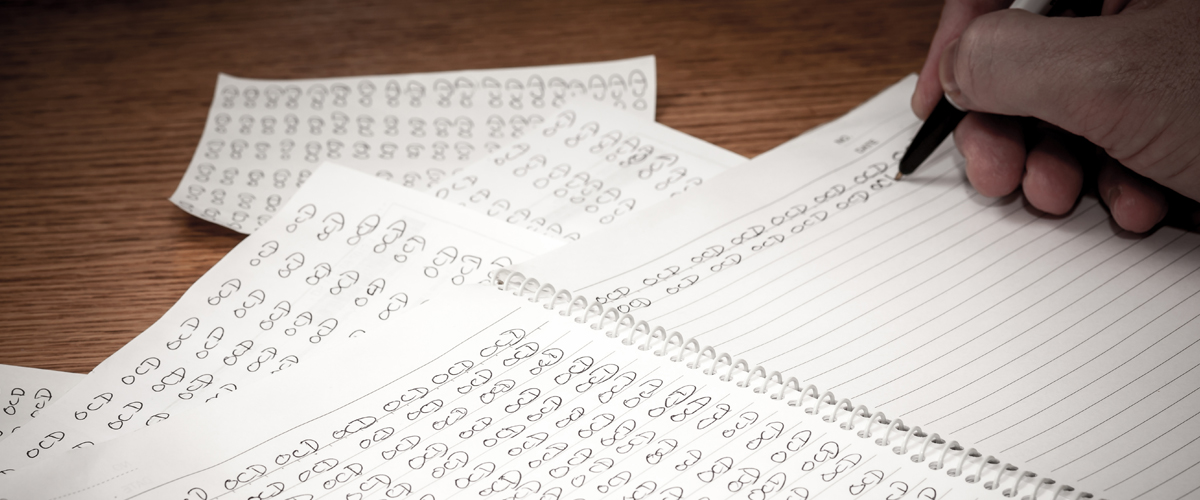

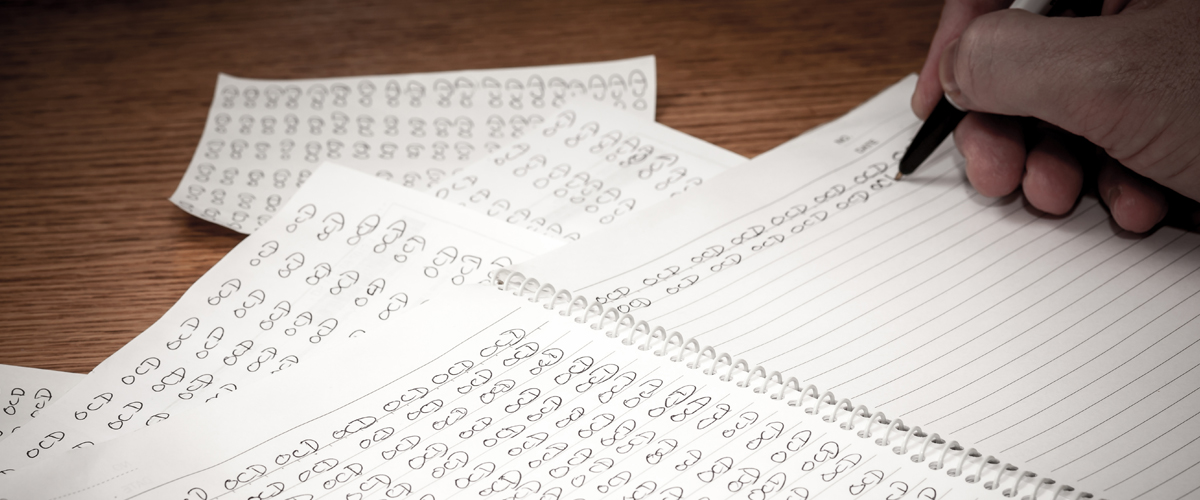

When people think of obsessive compulsive disorder, they may think of someone washing their hands a lot, or repeating things a certain number of times. What makes it a disorder is how debilitating it is to someone’s life. For people who have to write things over and over until it feels perfect, they might not be able to write at all because it so burdens them to write even one sentence, or they may have to do certain compulsions every time they walk somewhere. People may also have intrusive thoughts, which can interfere with quality of life.

What are intrusive thoughts, and how are they a symptom of OCD?

Intrusive thoughts are thoughts that intrude upon us that we don’t like, don’t want, and don’t agree with. Everyone has weird thoughts sometimes and they can be about anything. For example, if you’re standing on the subway platform, you may think how easy it could be to push someone or that you could be pushed yourself. Most people can then move on to a logical conclusion for the thought, such as, “I guess that entered my head because I’m contemplating how crazy the New York City subway system is.”

For individuals with OCD, the thoughts are stickier, and they give them more credit. They may grow concerned that the thought has entered their head, and question why it did and what it means about them, wondering if there is a part of them that wants to hurt someone, even though they are the least likely person to do so. They are so horrified about having had a thought about harming someone that they may do all sorts of compulsions to make sure they don’t hurt anybody, or avoid the subway all together, or confess these thoughts to others. They may repeat to themselves, “Don’t think about it, don’t think about it,” which, of course, makes them think about it more. This is a type of OCD less spoken about, one that can be very debilitating.

How can someone tell if they have OCD?

If a person’s obsessions and compulsions are taking a lot of time and interfering with life and functioning, they may have OCD. I often ask people, “Could you do it in another way?” If someone likes to check the stove before they go to bed to make sure it’s off, and I were to say, “Please don’t check tonight!,” could the person do it? Would they be OK? Somebody who is struggling with OCD often feels like they are unable to approach the situation any other way.

What causes OCD?

The understanding among experts is that it’s a mixture of genetic and environmental factors. It runs in families, and we have good research showing there is a genetic component. There is clearly an environmental component as well, since not everyone who is predisposed to OCD develops it. OCD grows over time: Every time you do a compulsion, you feel immediate relief, and that relief feels really good even though it’s only temporary. Hand washing brings relief to people who are afraid of germs, even if they don’t want to wash their hands all the time or their hands are raw and bleeding. But in that moment of relief, there is a reward to the system, training the person to do the compulsion again and again.

“For individuals with OCD, the thoughts are stickier, and they give them more credit.”— Dr. Avital Falk

How is OCD treated?

The gold standard treatment combines cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) with a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI). While both CBT alone and medication alone work well to treat OCD, the combination is the most effective intervention. CBT involves working on our cognitions and thoughts, and shifting them to become more realistic, along with exposure and response prevention (ERP), which is teaching people how to face the things that are difficult by exposing them to whatever their obsession is about, and then preventing the rituals or compulsions. The exposure might mean touching things that could have germs, and the response prevention would be refraining from washing your hands later. If I had somebody in my office and we spent the whole session walking around and touching things she felt afraid of, but then the person went home and scrubbed her hands for 20 minutes, she wouldn’t learn anything. She would think that she was only OK because she had washed her hands. The treatment is focused on having people face what is difficult for them and learning that the things they fear often don’t come true, or, that even if they do come true, they can probably handle them better than they thought they could.

While it’s hard to snap your fingers and say, “Stop feeling this way!,” we do have a little bit of control over the way we think about things and our behaviors. By shifting those two areas, we shift the way that we feel as well.

There is also research showing that transcranial magnetic stimulation, a noninvasive procedure that involves placing electromagnetic coils against the scalp to stimulate nerve cells in the brain, which has been used for treatment-resistant depression, can help. The FDA recently cleared it for the treatment of OCD.

Is there a cure?

While there is no cure, OCD can be managed so that people can be symptom-free. But they have to maintain the skill set they have. Someone who had compulsive hand washing may need to avoid hand sanitizer because that could put him at risk of falling back into his pattern. During treatment, we focus on maintenance and relapse prevention to train people to be aware of warning signs and triggers, and to have the skills to face the things they are afraid of so that their bigger symptoms don’t return.

What is important for people to know about OCD?

A lot of people suffer in silence and are hesitant to talk about OCD, or may even think they are going crazy, particularly if the thoughts are about harm or have anything to do with sexuality or a taboo topic. One of the biggest barriers we’re finding with OCD is that it takes people a long time to get a proper diagnosis, and then even longer to find the right treatment. I once treated a child who was so excited to get his diagnosis because he finally understood what was going on for him: There was a name for his suffering, and an established treatment for it.

This is a disorder that can be extremely debilitating, but for which we have treatments that can help. We have an intensive treatment program here at NewYork-Presbyterian and Weill Cornell Medicine that is a part of our Youth Anxiety Center, which allows people to condense treatment, meaning we work with them more hours per week — we know from the literature that people get better faster when you treat them in a shorter time period. Through group, individual, or family work, we get people back to functioning and back to their lives as soon as possible. The program is constructed around school and work hours so that people don’t necessarily need to take a break from things if they don’t need to.

What I love about doing this work is that people get better, and they get better quickly. There are excellent treatments out there if you find the right provider who is providing CBT and ERP. People with OCD should know there is a light at the end of the tunnel.

For more information on OCD treatment and services at NewYork-Presbyterian, visit the Department of Psychiatry at NewYork-Presbyterian.

Avital Falk, Ph.D., is the program director for the Intensive Treatment Program for OCD and Anxiety at the NewYork-Presbyterian Youth Anxiety Center and the director of the Pediatric OCD, Anxiety, and Tic Disorders Program at Weill Cornell Medicine. She is also an assistant professor of psychology in clinical psychiatry at Weill Cornell Medicine.