How NewYork-Presbyterian is Taking Aim at Obesity

Addressing this epidemic requires a multi-pronged approach that is both educational and action-oriented.

There is no shortage of information about the importance of nutritious meals and regular exercise in achieving and maintaining a healthy weight.

But for the families that Dr. Dodi Meyer sees as the director of community pediatrics at NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia University Medical Center, overcoming obesity isn’t as simple as cooking extra vegetables for dinner and signing up for a Little League team.

“A lot of things you do to create a healthy lifestyle don’t apply to these patients,” says Dr. Meyer, who is also a pediatrician and associate professor of pediatrics at Columbia University Medical Center. “These families often live in extreme poverty. They rent a room, not a home, and don’t have fully equipped kitchens or kitchen tables for regular mealtimes.”

Instead, Dr. Meyer focuses on accessible exercise like playing tag at local parks or getting off the subway one stop early and walking home. She advises skipping soda and juice in favor of water and suggests meals that are simple to prepare, nutritious, and budget-friendly.

Dr. Meyer also visits schools in Washington Heights and Inwood to address the 45 percent of students who are overweight or obese in school district 6, compared to 21 percent in New York City, according to Citizens’ Committee for Children of New York (CCC); this statistic represents four of the seven schools in the program for which data is available. Just under 26 percent of public elementary and middle school students in Washington Heights and Inwood are obese compared to 21 percent of public elementary and middle school students.

Through the Choosing Healthy and Active Lifestyles for Kids (CHALK) program, pictured above, a 13-year-old partnership between the NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital Ambulatory Care Network and the Columbia University Medical Center Community Pediatrics program, Dr. Meyer has introduced healthy snack policies in schools and promotes active recesses. A CHALK-sponsored “Just Move” toolkit uses flashcards to lead in-class exercises such as yoga, aerobic drills, and stretching while weaving in math, science, and English core lessons to promote, simultaneously, physical activity and academics. CHALK also helped establish Fort Washington Greenmarket to increase access to healthy foods.

“Our goal is to change the environment so a healthy lifestyle isn’t done by choice,” Dr. Meyer says. “It’s done by default.”

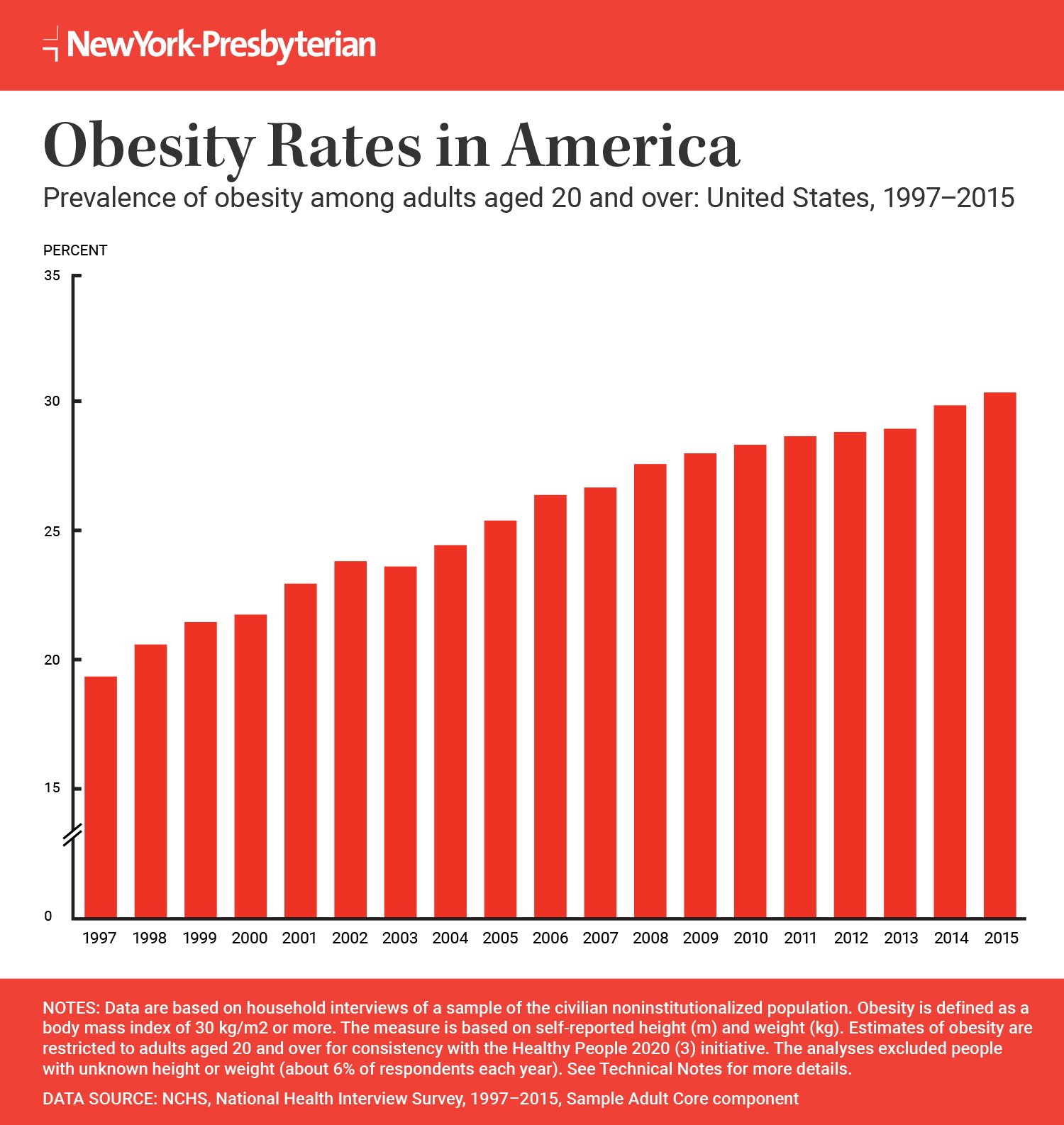

This intervention is essential. Today, 38 percent of adults, 21 percent of youths ages 12 to 19, and 17 percent of kids ages 6 to 11 are obese in the U.S. Even more staggering: 9 percent of kids younger than 5 are obese, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

For those ages 2 to 19, obesity is diagnosed when body mass index, or BMI, a formula that calculates the ratio of weight to height, is at or above the 95th percentile for their age. Adults are diagnosed as obese when their BMI is 30 or above.

The health impacts of obesity are clear — obesity is linked to a range of conditions such as type 2 diabetes, high blood pressure, heart disease, stroke, and osteoarthritis.

“There are more cheap, high-calorie foods, more [reliance on] transportation, [more] screen time, and less exercise,” says Dr. Marc Bessler, director of the Center for Metabolic and Weight Loss Surgery at NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia University Medical Center and the United States Surgical Professor of Surgery at Columbia University Medical Center. “The environment has ganged up on genetics.”

Confronting the Issue in Childhood

The best way to offset these factors and prevent childhood obesity from extending into adulthood is addressing lifestyle factors like diet and exercise early in life, says Dr. Marisa Censani, a pediatric endocrinologist and obesity medicine specialist.

“If we can intervene early on and prevent [future health] complications,” she says, “we’re giving children a healthy future.”

In her role as the director of the Pediatric Obesity Program at NewYork-Presbyterian Komansky Center for Children’s Health, Dr. Censani oversees the Kids and Teens Healthy Weight Program. Doctors refer overweight and obese children to one-hour weekly sessions, which aim to make obesity education fun and informative through games, cooking demonstrations, and other interactive activities like Nutrition Jeopardy and food-label reading workshops.

One participant, a 14-year-old boy, was already experiencing the negative health effects of obesity when he joined the program. He was diagnosed with insulin resistance, type 2 diabetes, and high cholesterol; his self-esteem also suffered. Through diet and lifestyle changes, he lost 50 pounds over six months. His cholesterol level returned to normal; his A1c, a measure of blood glucose over time, returned to normal; and his insulin resistance resolved. In short, the weight loss reversed his type 2 diabetes.

“His whole family got involved to make changes and it worked,” says Dr. Censani, also an assistant attending pediatrician at NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center and assistant professor of pediatrics at Weill Cornell Medicine. “He felt healthier and had a lot more energy. We were so proud — and he was so proud.”

Both Drs. Meyer and Censani agree that a multidisciplinary team that includes pediatricians, nutritionists, and psychologists who take a community-based approach to obesity education and intervention is most effective. It takes a holistic approach to change the environment where children live and play to encourage healthy, active lifestyles, they say.

Appropriate Interventions

To be effective, approaches to changing a child’s environment must be culturally appropriate since certain ethnic backgrounds mean a higher risk of obesity, says Dr. Censani.

The National Institutes of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases reports that 26 percent of black youths ages 6 to 19 and 23 percent of Hispanic youths are obese, compared with 15 percent of white youths. More than 41 percent of black and Hispanic youths are overweight or obese compared with 29 percent of whites in that age group.

“If we can intervene early on and prevent [future health] complications, we’re giving children a healthy future.”— Dr. Marisa Censani

CHALK launched its community intervention in the Washington Heights neighborhood, where the campaign messages are embedded into the school-based program and spread by local businesses and community organizations. The campaign aims to get the entire community — community members, activists, church leaders, artists, and local food establishments — to embrace healthier habits by joining the campaign and promoting at least one of the 10 Healthy Habits, which include eating less fast food, being physically active every day, drinking water instead of soda or juice, and more.

To further educate the at-risk population with whom she works, Dr. Meyer focuses on changing widely held cultural beliefs that might stand in the way of healthy habits.

“There is a cultural issue that a chubby baby is a healthy baby, and we explain that it might be cute, but it’s not the healthiest,” she says. “It’s not about blaming the parents but educating them very early about the impact obesity has on health. We need to start these interventions prenatally.”

When Change Isn’t Enough

For some, diet and exercise aren’t enough to overcome obesity.

Pamela Frazier tried countless diets in her quest to lose weight, starting as a teenager and dieting into adulthood. The corporate trainer, 41, would lose five, 10, sometimes 20 pounds, only to gain it all back. The excess weight was causing fatigue, joint pain, and impaired mobility. In 2015, Pamela contacted the Minimal Access Surgery Center at NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia University Medical Center about gastric bypass surgery, a surgery that shrinks the size of the stomach to minimize the amount of food that can be consumed.

“I needed a more permanent option,” she says.

Prior to surgery, Pamela underwent four months of preparation that included appointments with nutritionists and therapists and a supervised weight loss program.

Pamela had the surgery April 20, 2016. In the months since, she’s lost 60 pounds and says she feels great. Thanks to the ongoing support of the team at NewYork-Presbyterian, Pamela now eats less, wears a fitness tracker to incorporate more movement into her days, and has access to support groups both within the hospital and outside. She is aiming to lose another 60 pounds. She’s set a goal to run a half-marathon.

“My energy is back. I have more mobility,” she says. “Without the surgery, I’m sure I’d be taking insulin [for type 2 diabetes] by now. The weight loss surgery has given me a new lease on life!”

These kinds of success stories reflect advances in both weight loss surgery and attitudes about obesity, according to Dr. Bessler.

“Twenty years ago, we were still blaming patients for being overweight, not talking about obesity in medical school, or treating it as a disease,” he explains. “My dad was morbidly obese and I saw how it affected his health and quality of life. I knew I could have an impact.”

As founder of the Comprehensive Obesity and Metabolism Management and Treatment (COMMiT) program, Dr. Bessler combines mindful eating classes and participation in 12-step programs like Overeaters Anonymous with weight loss options such as a removable gastric balloon, nonsurgical stomach reduction, and minimally invasive surgery.

Dr. Bessler says the multipronged approach is the best way to address adult obesity.

“There are so many causes of obesity, like social, environmental, genetic,” he explains. “You need doctors, nurse practitioners, nurses, and social workers to help patients learn different habits to live their lives differently. Without education, we can’t expect people to change.”

Research shows the odds are good that patients who undergo weight loss surgery achieve long-term success. A 2016 study published in JAMA: the Journal of the American Medical Association, followed patients for 10 years after weight loss surgery and found that they had lost 21 percent more of their baseline weight than the nonsurgical group. Only 3.4 percent of the weight loss surgery patients had returned to their baseline weight. In contrast, 55.5 percent of the nonsurgical group had gained back the weight they had lost.

To increase the odds of success, patients undergo rigorous pre-surgery preparation that includes education on the importance of exercise for boosting metabolism; choosing nutritious, filling foods over processed foods; and sipping water instead of sugary beverages. Embracing new habits is essential because, without lifestyle changes, patients are more likely to gain the weight back after surgery, according to Dr. Bessler.

While bariatric surgery is not the right option for everyone, Dr. Bessler says it has the potential to be life-changing.

“Obesity is a chronic disease that is directly related to serious health problems,” he says. “Surgery is a safe and effective treatment and you can get years of your life back by availing yourself of that treatment.”