How a Routine Brain Surgery to Treat Epileptic Seizures Became Lifesaving Amid the Pandemic

Tracey Drake needed a new battery for the device in her brain that manages her epilepsy. But the coronavirus outbreak made the procedure anything but easy.

When a low-battery alert pops up on your mobile phone, it can spark a small feeling of panic.

Now imagine getting that same notification — but for a device in your brain.

On March 4, Tracey Drake, who has been living with a severe form of epilepsy for almost 20 years, learned that the responsive neurostimulation (RNS) device that is implanted in her brain to help manage her epileptic seizures was losing power.

“Her battery was starting to get low, so we started talking to Tracey about replacing it,” says Dr. Steven Karceski, a neurologist at NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center who has treated Drake since 2001.

This wasn’t the first time this had happened since the device was implanted in 2014. “It had been over three years since we replaced the last battery,” explains Dr. Karceski, who is also an assistant professor of neurology at Weill Cornell Medicine. “That’s how long we expected it to last, so we knew we needed to replace the battery again soon.” The team set Drake’s surgery for March 17.

Then COVID-19 hit.

Although replacing the battery in an RNS device is a routine procedure, Drake needed it done at a time when everything was far from routine. As the coronavirus outbreak wreaked havoc on the city and pushed healthcare workers to their limits, NewYork-Presbyterian postponed elective procedures just one day before Drake was scheduled to go into the operating room.

“I thought, ‘Oh no, what am I going to do?!’” recalls Drake, 47. “I started worrying that my device would run out of power.”

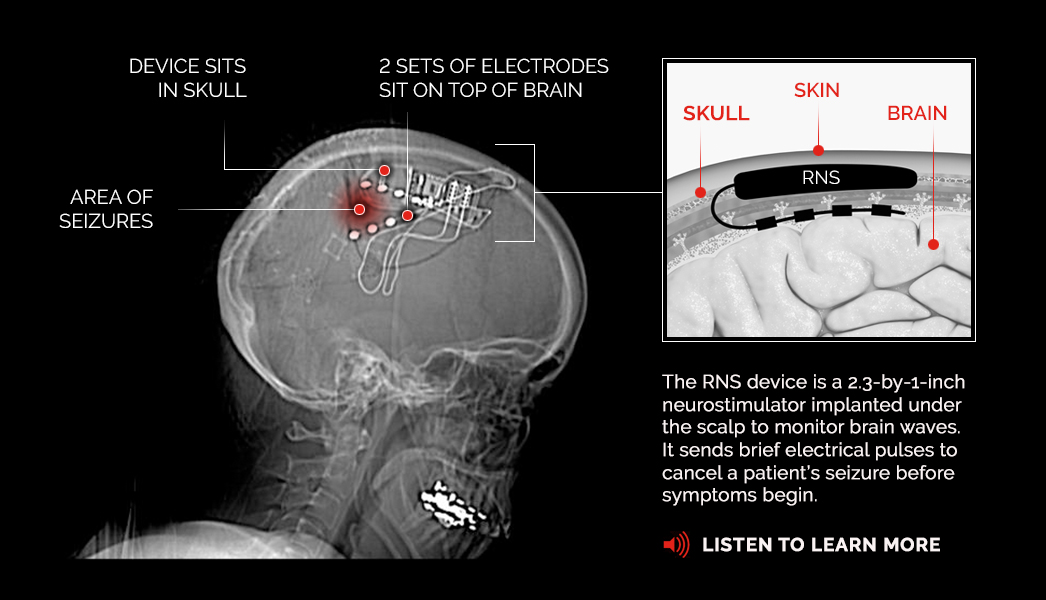

How Responsive Neurostimulation (RNS) Works

A Life-Changing Device

Drake lives with refractory epilepsy, a challenging form of the disease that does not respond to medications and affects more than 2 million people in the United States.

On a daily basis, Drake would battle epileptic seizures that ranged from brief numb and tingling sensations throughout her face and arms to an unrelenting cycle of three-minute episodes that left her disoriented, drained, and eventually bedridden.

“She was having seizures one right after the other,” says Dr. Karceski, who suggested Drake try the RNS device, which the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved as a new treatment for epilepsy in 2013.

RNS treatment involves implanting a neurostimulator that sits in the skull and has two electrical wires, or leads, that connect to the area of the brain where Drake’s seizures occur. When the device senses abnormal activity, it sends a small electrical pulse that negates the epileptic seizure before Drake even feels any symptoms.

“The RNS device completely turned my life around,” says Drake. “I don’t even think about seizures. They don’t control me anymore.”

But if the device suddenly stopped working, says Dr. Karceski, “her seizures would have gotten worse, not only in frequency but in severity as well.”

“The RNS device completely turned my life around. I don’t even think about seizures. They don’t control me anymore.”— Tracey Drake

Remote Reassurance

Dr. Karceski wasn’t about to let that happen. He was regularly monitoring her brain activity remotely, analyzing her brain waves and battery levels thanks to the information Drake downloaded from her RNS device to a shared database multiple times a week.

“I was calling her often to reassure her that her battery was still OK and not to worry. And she would say, ‘I’m so glad you called because I keep thinking it’s going to run out,’” says Dr. Karceski.

“We were doing this for all of our patients, especially during the quarantine,” adds Dr. Karceski. “We were checking in and monitoring them as often as we could because we don’t want these devices to run down faster than we expect and then have problems.”

After two months, however, Drake’s device had an elective replacement indicator (ERI) alert, which meant the battery was on its last legs. “We probably had about three months to get the surgery done, but we didn’t want to take a chance,” says Dr. Karceski.

As surgeries resumed at NewYork-Presbyterian, Dr. Theodore Schwartz, director of epilepsy surgery at NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center, presented Drake’s case to a departmental review board, asking for approval to bring her in.

“Her surgery was not an emergency, but if her seizures are not controlled, she would be at risk of having an adverse event that could cause permanent damage to her brain and her body,” says Dr. Schwartz, who implanted Drake’s RNS device in 2014.

“One of the reasons why we are so aggressive in treating seizures is that we know that there are rare but very serious consequences,” adds Dr. Karceski. “A serious seizure where there are convulsions and the patient loses consciousness can cause injuries and possibly death.”

The approval was immediate, and within nine days Drake arrived at NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center to have the procedure on June 10.

The “Bad Days”

While the operation is fairly common, for Drake, it was more than a simple procedure. The small battery is the difference between a life filled with unforgiving seizures or uninhibited joy.

Before she had the RNS device, “she would have dozens, if not hundreds, of seizures a day,” says Dr. Karceski.

“Sometimes the seizures would be so powerful that I would sleep the whole day or two days,” says Drake, who called those incidents her “bad days.”

“I could be having a conversation with people, and if they had asked me a question, instead of responding right away, it might take me a few minutes to answer,” she says. “And if the seizures progressed and became longer, I wouldn’t be coherent.”

As her epileptic seizures became stronger and more unpredictable, “I wouldn’t make plans,” she says. “I didn’t want to have a seizure in front of anyone, so I alienated myself.”

Drake even resigned from her position as chief of the local fire department, where she was the first woman to hold the leadership role. “I really took a big step back from everything,” she says. “The seizures were controlling my life.”

Growing up, Drake was always active on her family’s farm in Long Valley, New Jersey, where she and her two brothers would help care for the animals or pitch in at their produce stand. But in 1999, during a family vacation to Long Beach Island along the Jersey shore, Drake noticed that her vision was blurry and she was having trouble breathing.

“I couldn’t focus and I felt foggy,” Drake says. “My body didn’t feel right.”

A trip to the emergency room yielded a gamut of tests, including an MRI that showed Drake had a cavernous malformation, an abnormal cluster of blood vessels that had burst, causing a bleed in her brain.

Drake decided to seek treatment immediately. “I talked to a few doctors,” she says. “One neurosurgeon told me that there was nothing they could do for me so try to live with it.”

After a year of getting second, third, and many more opinions with her mom, Rosemary, by her side, a nursing friend suggested going to NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving Medical Center, where Drake had surgery to remove the cluster of blood vessels. But the scar tissue that remained became the focal point for Drake’s epileptic seizures, a common side effect of cavernous malformations.

A Patient-Doctor Partnership

At NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving Medical Center, Drake also met Dr. Karceski, who, she says, “always has a positive vibe coming from him and always has been reassuring” as he helped her navigate treatments for her epilepsy over the last 19 years.

Over the past two decades, Dr. Karceski, who now practices at NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center, has tried numerous regimens to treat Drake’s epileptic seizures with various degrees of success.

“We tried more medications than I knew even existed for seizures — different combinations, doses, you name it,” says Drake.

Tracey Drake near her home in Long Valley, N.J. post-surgery.

“At times it got very frustrating, and I would almost give up. But Dr. Karceski just wouldn’t allow it,” she says. “If one medicine didn’t work, he always had another thing we could try. He never gave up. There was always the reassurance that we were going to keep fighting this together.”

During the course of her treatment, Drake also underwent two other surgeries, one of which involved implanting a different device known as a vagus nerve stimulator (VNS). The VNS device helped Drake manage her epileptic seizures for a short time. But it was not as effective as she had hoped for, and she suffered some unwelcome side effects such as changes to her voice.

Finally in 2014, Dr. Karceski recommended the latest epilepsy treatment to hit the market: the RNS device.

Drake gave him a swift no. “I told him no more surgeries,” says Drake. “I had enough. Every time we did one, it worked for a little bit, and then it didn’t work. I was tired. No more.”

Despite Drake’s firm reaction, Dr. Karceski sent Drake home with information about the RNS and suggested that she talk to some of the patients who had taken part in NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center’s successful clinical trials for the device.

“NewYork-Presbyterian has been right on the cutting edge of all three devices that are available for the treatment of epilepsy,” says Dr. Karceski. “Both Columbia and Weill Cornell have been at the forefront of doing some of the early, if not initial, research to figure out if they would work.”

Though she remained determined to avoid another surgery, her epileptic seizures were getting progressively worse. “One option would have been to try more medications, but that felt like I was going backward,” says Drake. So after a month of learning more about the RNS, Drake told Dr. Karceski, “Let’s give it a shot. It can only go forward from here.”

“Tracey went from having lots of ‘bad days’ in a month to having one or two bad days in the last couple of years.”— Dr. Steven Karceski

Planning for the Future — for the First Time

In fact, Drake fast-forwarded to a life that was practically seizure-free shortly after the device was implanted.

“Tracey went from having lots of ‘bad days’ in a month to having one or two bad days in the last couple of years,” says Dr. Karceski.

Now with the new battery in place, Drake, who lives with her brother, Josh, and his wife, Jen, can focus on helping out with her 3-year-old niece, Ella, and 6-year-old nephew, Cooper, and volunteering at the fire department. She’s also making plans for the future since she doesn’t have to worry about battery replacement surgery for another eight years.

“Before, I would only look ahead maybe two years,” says Drake. “Now I don’t have to worry about my seizures for a long time. That is a big step for me.”

For Dr. Karceski and Drake’s entire care team at NewYork-Presbyterian, that was the ultimate goal. “It’s not about treating the disease. It’s about treating the person,” says Dr. Karceski. “We don’t just want to help patients get better. We’re focused on giving them a better quality of life in the long run.”