What To Know About New Alzheimer’s Disease Treatments

Lecanemab, an antibody treatment administered intravenously, is clinically proven to slow the rate of cognitive decline, and an injectable form of the therapy could be on the horizon.

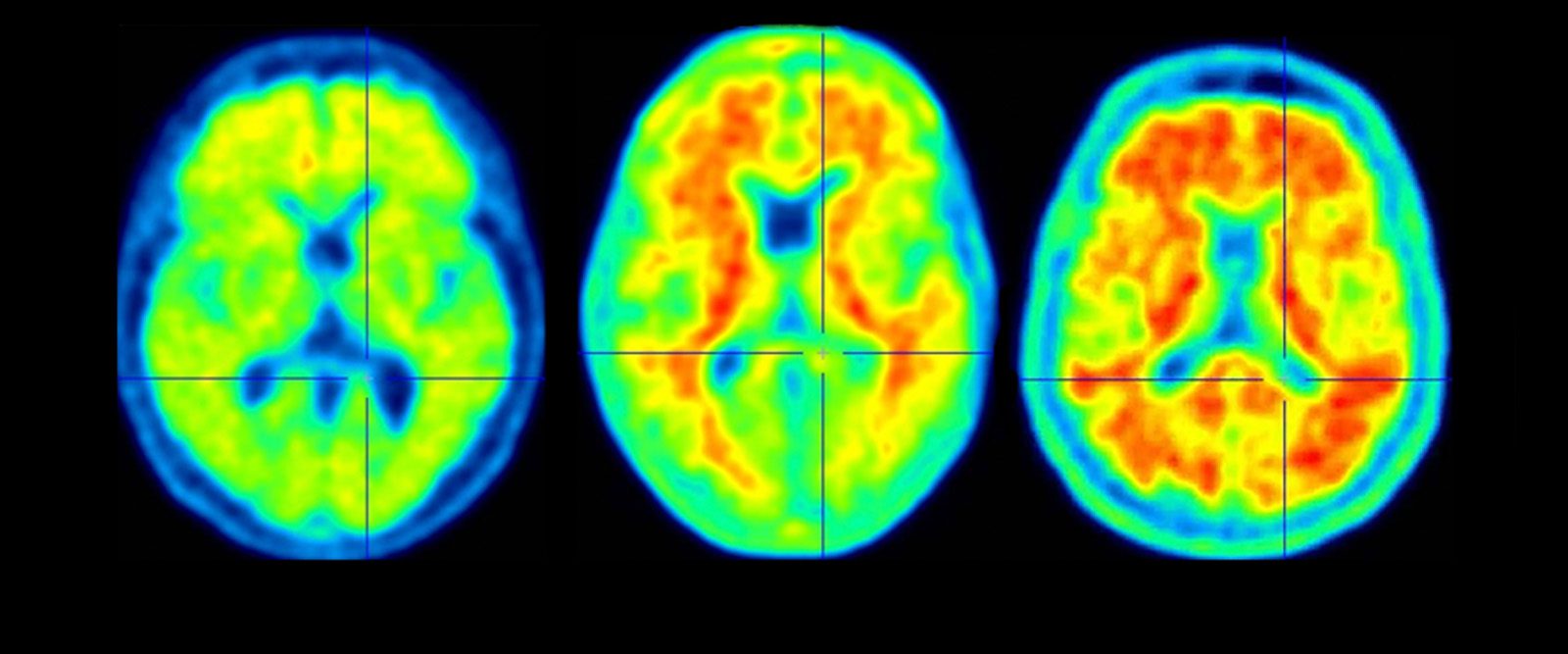

A scan of a healthy brain (left) and scans of brains with accumulations of amyloid (in red), a protein that increases the risk of Alzheimer’s disease.

Lecanemab, a therapy that targets amyloid proteins thought to cause Alzheimer’s disease, was granted full approval by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) earlier this year, marking a major breakthrough in the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease, which affects approximately 6 million people in the U.S.

Alzheimer’s is associated with abnormal accumulations of the protein beta-amyloid, which forms plaques in the brain tissue, affecting memory and thinking abilities. “Lecanemab targets certain forms of the beta-amyloid protein in the brain of people with early-stage Alzheimer’s disease,” says Dr. Lawrence S. Honig, a neurologist at NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving Medical Center. “Clinical trials found dramatic evidence of removal of amyloid proteins in the brain by the intravenous version of the treatment and clinically proved that it slowed down the progression of the disease.”

Neurologists at NewYork-Presbyterian have begun to administer lecanemab, marketed as Leqembi, to patients at the Columbia and Cornell locations. Every two weeks, the patients receive the therapy intravenously.

Dr. Lawrence Honig

Now, a subcutaneous version of lecanemab – consisting of weekly injections under the skin – is showing promising results, according to data recently shared by Eisai, one of the manufacturers of the therapy, at the 16th annual Clinical Trials on Alzheimer’s Disease conference.

Dr. Honig spoke with Health Matters about how lecanemab works, its risks, and the FDA’s approval of the drug.

How does lecanemab work? What promise does the therapy hold?

Dr. Honig: Lecanemab is a monoclonal antibody that binds amyloid and was designed to remove amyloid from the brain. It has long been suggested that removing the protein might slow the progression of Alzheimer’s disease.

In the clinical trial, the treatment was administered every two weeks by intravenous infusion. The trial results showed that it slowed decline for people with early Alzheimer’s disease by about 27% to 37%, depending on the clinical test measure. After 18 months of treatment, the mean amyloid level in most treated patients was below the threshold for amyloid positivity, meaning that a radiologist would not even know the patient had Alzheimer’s disease.

In preliminary results of a substudy on subcutaneous lecanemab, patients who received weekly injections of the therapy showed comparable amyloid plaque removal and similar side effects to those who got lecanemab intravenously biweekly.

Does lecanemab reverse problems linked to Alzheimer’s disease, its signs, and its symptoms? It does not. Does it slow them down? It does, by a variety of measures; one, by reducing amyloid levels. And this is the first medication clinically proven to do so.

Are there other Alzheimer’s treatments?

Donanemab is another drug of the same class. Like lecanemab, it removes beta amyloid and slows disease progression. Eli Lilly, its manufacturer, submitted to the FDA for full approval, and a decision is expected sometime around the end of 2023.

The FDA granted aducanumab, a similar treatment, accelerated approval in 2021 based on it demonstrating amyloid removal from the brain. But aducanumab did not have clear evidence of clinical efficacy in Alzheimer’s disease, such as proven slowing of the progression of cognitive decline, and this drug does not have full FDA approval at this time.

How many participants in the clinical trial of lecanemab experienced the associated risks, and what is there to know about these risks?

The main risks of amyloid-lowering medications include brain swelling (ARIA-E) and brain bleeding (called ARIA-H), which participants in both the main intravenous study and subcutaneous substudy experienced.

Almost 13% of participants who were on intravenous lecanemab experienced brain swelling. There were 3% that had what is called symptomatic brain swelling, which means that they had swelling of the brain that caused clinical signs or symptoms, and less than 1% had serious symptoms. The bleeding events in the brain, called “micro-bleeds,” are rather common in Alzheimer’s disease, and in the absence of the swelling there was no difference between rate of bleeding events in those on treatment and placebo. It is rare that patients have symptoms from a micro-bleed; it is noticed by the neurologists or radiologists looking at the scans.

Understanding Findings of Clinical Trials on Intravenous Lecanemab

Lecanemab’s traditional approval followed a confirmatory trial published in The New England Journal of Medicine. The data showed that the drug slowed functional losses and cognitive decline, such as memory loss, in a Phase 3 clinical trial of 1,795 participants between 50 to 90 years of age who were in the early stages of Alzheimer’s disease. In clinical trials, Phase 3 is the last testing phase before a drug, such as lecanemab, is submitted for regulatory approval and released in the market.

All participants in the trial were experiencing mild cognitive impairment or mild dementia due to the disease and were required to have biomarker evidence of Alzheimer’s disease, based on examination of their cerebrospinal fluid or on nuclear medicine imaging. To determine the progression of Alzheimer’s disease in participants, a variety of scales were used. These scales captured measurements of a person’s cognition and their function, including things such as their memory, problem-solving abilities, and capacity to perform daily activities, through interviews with patients and their caregivers.

The treatment markedly reduced brain amyloid levels determined by PET imaging and lessened neurodegeneration (when nerve cells stop working or die) in the spinal fluid.

What do we know about subcutaneous or injectable lecanemab?

The subcutaneous substudy included 72 patients who received lecanemab for the first time as the subcutaneous formulation, and 322 patients who originally received lecanemab intravenously in the Phase 3 clinical trial, but then received subcutaneous administration in this substudy.

Patients showed similar concentrations of drug by injection under the skin once a week by intravenous infusion every two weeks. In some ways, the delivery looked more favorable: Instead of the ups and downs seen with the intravenous infusion, with high concentrations of drug and then lower concentrations as time goes on, with the subcutaneous injection, it seems like the level of the drug was more stable and consistent.

What are the next steps for the subcutaneous version?

In the coming months, subcutaneous lecanemab will be studied more and is expected to be submitted to the FDA for approval in March 2024, with a decision most likely to be made later that year.

Since lecanemab was granted full approval, who can access the treatment and how?

Since full approval was granted in July, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) has announced the availability of coverage with some restrictions for this medication, and it is expected that there will be increased usage of the therapy. However, it is only indicated for people who have early Alzheimer’s disease, namely either mild cognitive impairment or mild dementia due to this disease. It is also only warranted when there is confirmation of the presence of beta-amyloid brain pathology.

CMS said that the therapy will be covered as long as the prescribing physician and clinical team provide data to a privacy-protected registry on how patients are doing while on the treatment. The registry is a database designed to collect information about how the drug works in the real world.

Lawrence S. Honig, M.D., Ph.D., is a neurologist at NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving Medical Center and professor of neurology at the Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons, specifically in its Department of Neurology, the Taub Institute for Research on Alzheimer’s Disease and the Aging Brain, and the Gertrude H. Sergievsky Center, where he directs the New York State funded Center of Excellence for Alzheimer’s Disease. Dr. Honig’s clinical specializations focus on Alzheimer’s disease, Lewy body dementia, frontotemporal dementia, progressive supranuclear palsy, Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, immune-mediated encephalitis, and other disorders of nervous system aging and degeneration.

Dr. Honig was an investigator for lecanemab’s CLARITY AD clinical trial carried out at NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia and has been an investigator and received research funding from Biogen Eisai, and Lilly for other drug studies. He also has consulted for Eisai, the pharmaceutical company developing lecanemab, as well as for Biogen, Cortexyme, Genentech, Lilly, Prevail, and Roche pharmaceutical companies.